Coronation Street #3109 (17 August 1990) Class war reaches Weatherfield as Des and Steph Barnes move into the new home at Number 6.

Snooping on Don Brennan from the Back Garden: Watching Coronation Street in the 1990s.

For much of my twenties in the 1990s and early 2000s, before my eventual career as a Television Studies academic, I worked as a library assistant. Over years of tea breaks in library staff rooms I overheard (and occasionally contributed to) many conversations about soap operas, always Coronation Street (ITV, Granada, 1960-) and EastEnders (BBC1, 1985-). The content of these conversations generally took two forms: judgment over the rightness or wrongness of characters and their actions (“I was really sorry for Gail when Martin had a one night stand with that nurse“), and speculation as to how events would progress (“Who do you think shot Grant Mitchell?”). More general consideration of these soaps as programmes in themselves was infrequent and generally took the form of complaints about how they weren’t what they used to be (“It’s too depressing these days/ there are too many young people/ gangsters in it now”)

Because of this, one very atypical tea break discussion has always stayed in my mind. Decades later, thanks to the invaluable and exhaustive resource of Corriepedia I can trace the precise episode that we were talking about – #3395, 10 June 1992. The reason why this conversation was so unusual is because we weren’t talking about Rita‘s marriage to Ted Sullivan, or Emily Bishop‘s protracted nervous breakdown, but how the programme was shot and the means by which the director (Julian Farino) had conveyed plot information to the audience. A routine scene – “Don Brennan takes time out to track Julie Dewhurst down and give her lifts in the cab. She cooks him a meal when he persists being with her.” – had not been shown from inside the living room where it was taking place, but partially observed though a window from Julie’s back garden. What was all that about? We couldn’t understand what it was supposed to signify. Did this mean that somebody else was aware of Don’s actions and was spying on him? Surely not Ivy? If so, then why weren’t we subsequently shown who the watcher in the garden was?

What none of us understood at the time was that the odd way that this scene had been realised was not because of anything to do with the story of Don Brennan’s hoped-for infidelity, but because the visual grammar of how Coronation Street was made was changing before our eyes. Although much of the appeal of, and emotional investment that the dedicated viewer places in, Coronation Street derives from a sense of familiarity and continuity, throughout the 1990s the form, structure and feel of the programme was actually radically, but largely invisibly, changing. What was most significant about the audience being placed in Julie Dewhurst’s garden was that momentarily – through an incidence of badly misjudged direction – the curtain was lifted and viewers such as my colleagues and myself were made aware of the changing ontology of Coronation Street as it occurred.

Changing production and broadcast of Coronation Street in the 1990s.

Coronation Street underwent two near-concurrent major changes to its production practice towards the end of the 1980s, changes that inexorably altered both the form and dramatic function of the programme. The first change, in 1988, was switching the recording of location sequences from 16mm film to videotaped Outside Broadcast (OB) (Little, 2000: 188). Using more transportable and flexible OB recording technology enabled the programme to use many more exterior scenes than previously, creating a more mobile mise-en-scene more in line with the contemporary continuing series Brookside (Channel 4, Mersey TV, 1982-2003) and The Bill (ITV, Thames, 1984-2010). This increase in location sequences meant that for the first time the world of Coronation Street could regularly, rather than infrequently, go beyond the familiar cobbled street and onto the streets, houses and institutions of the wider world (from hereon referred to as ‘Greater Weatherfield’), with the programme featuring three or four outside locations each week by the 1990s (Hanson & Kingston, 1999: 58).

The second major change to the programme was a move to production and broadcast of three episodes per week in October 1989, Coronation Street having previously run twice weekly since its launch in 1960. Transmitting an extra edition of its highest-rated programme was a highly popular move within the ITV network, which had long suffered a problem with attracting substantial audiences on Friday nights (Kay, 1991: 24-5). The Street‘s executive producer David Liddiment (1988-92), explained the move to a third episode:

“We had already made the decision to increase the volume of location material and we were looking at a schedule to give us more time on location and the same time in the studio. I didn’t want the process we’d started, of increasing the production values of an episode, to be neutralised by the need to make a third episode. I wanted to make sure we could continue to enhance the production values of the programme and do a third episode. But there was a kind of rhythm about Monday, Wednesday and Friday, and the fact that Neighbours and Home and Away were being shown five days a week with healthy audiences was. I felt, indicative of our ability to hold an audience for an extra episode.” (1991: 24)

What is interesting about Liddiment’s justification is that it links both changes (mode of recording and amount of episodes) together, with increased location scenes constituting an increase in “production values”, an artistic advance that must be safeguarded.

Preparations for the introduction of a third episode were carefully considered, resulting in extensive changes to several essential aspects of the programme. The composition of the street itself was altered, with the demolition of the Baldwin’s Casuals clothing factory and Community Centre creating space for three new homes (numbers 4, 6 and 8). New houses required new residents, broadening the social mix of the series’ characters, a change that returning producer Mervyn Watson (1982-85, 1989-92) saw as creating fresh dramatic possibilities for the series:

“The reconstruction of the even-numbers side of the street has opened up a new swathe of stories and characters. It was appropriate that the first occupants of No 6 Coronation Street should be newcomers, the hot-tempered newlyweds Des and Steph Barnes. By mixing old and new, our well established characters have been given new possibilities and a new lease of life.” (in Kay, 1991: 31)

In order to fill 52 extra episodes per year without increasing the workload of the show’s actors, the number of regular and semi-regular characters increased from around 30 to around 40. In order to incorporate the greater number of characters and locations, the show also became faster-paced, incorporating more (and therefore shorter) scenes per episode.

At the same time that new outside broadcast technology was introduced, radical alterations were also being made to Granada’s facilities for the interior studio scenes that formed the bulk of Coronation Street‘s settings, with the opening of Stage One, an enormous new studio exclusively for the production of the programme, in 1990 (Hanson & Kingston, 1999: 51). The size of Stage One meant that permanent standing sets could be kept for interiors of all the Street’s houses and businesses for the first time, previously only kept for the main Rovers Return interior in the old studios (Podmore & Reece, 1990: 171). A further change to the making of studio scenes in the 1990s came with the introduction of Avid digital editing technology, greatly increasing opportunities for postproduction (Hanson & Kingston, 1999: 98).

Like Watson, Liddiment described the combined effect of these changes as creating opportunities to offer viewers a broader, more diverse and exciting dramatic experience than before:

“In the last few years, we’ve transformed the way we make programmes. Until a couple of years ago, each episode would probably have more than four or five different settings – either the shop or café and two or three interiors of houses, plus, at the most, two scenes shot outside on the street set or at a separate location. And each episode would have no more than 14 scenes. A typical episode now has eight or nine different interiors and four outside locations, and anything up to 22 or 23 scenes. We go more on location. We see more of Weatherfield than we used to. We see more of the street. At one time, that wouldn’t have happened because it was a luxury the schedule didn’t allow, but we make TV now with lighter equipment that requires less lighting, so you’ve got more time.” (in Kay, 1991: 26-8)

A more sceptical reaction to the changed production conditions of the late eighties was revealed in the memoirs of Watson’s predecessor, Bill Podmore (producer 1976-7, 1977-82, 1987-8, executive producer 1982-7). As well as expressing general concern about overkill dissipating viewers’ attachment to the series, Podmore had specific qualms about the increased volume of characters and storylines:

“New houses are to be built along the street and inevitably the cast must grow. It worries me just how many characters the viewers can absorb and care about. The more characters you have, the more each individual is diluted; you can’t feature them all at any one time. I thought we had already achieved the optimum balance, and perhaps even tipped the scales slightly on the down side. When I retired the cast numbered almost thirty and was the largest in the programme’s history. We would be constantly reminded of the dangers of an expanding cast at the writers’ conferences; we had trouble enough creating good story-lines for the characters we had, let alone others we might have like to introduce. The writers often complained we had too many as it was. To add perhaps another ten will mean that some characters – and possibly firm favourites with the viewers – may not be seen for quite long periods while storylines float around the others, Transmitting three days a week doesn’t mean that more story-lines can be crammed into any one episode. They will simply pass through the programme, and be used up, more speedily.” (Podmore & Reece, 1990: 178)

Although extra characters and storylines were added to fill the 25 minutes additional airtime (and make full use of the dramatic opportunities created by increased availability of location recording) without increasing the workload of performers, there still remained only seven days a week to produce three episodes of Coronation Street in and recording schedules changed accordingly.

A typical 1980s production week allocated all location filming (mostly of Street exteriors) to Monday mornings, followed by rehearsals for blocking in the afternoon. Tuesday rehearsals concentrated on performance and interpretation, with actors expected to be off script by final rehearsals on Wednesday morning. The full cast attended the Wednesday afternoon technical run, performed in front of the full crew (formed of technical supervisors, camera and sound operators, production assistants, ASMs, wardrobe, make-up and others). Any extra outdoor filming required was completed on Thursday morning, with studio recording starting at 2.30 p.m. and continuing over Friday when it had to be completed by 6.30 p.m. in order to be edited and dubbed over the weekend (Podmore & Reece 1990: 169-73)

In order to incorporate the extra episode, the 1990 working week was extended by a day, with outside location recording on Sunday, Street exteriors on Monday, rehearsals on Tuesday and Wednesday morning, technical run on Wednesday afternoon, with studio lighting set up overnight on Wednesday in preparation for two full days of studio recording between 9.00 a.m. and 6.30 p.m. on Thursday and Friday (Kay 1991: 62-3). Although (less) time for rehearsals was still kept, by the end of the decade (after the addition of a fourth Sunday episode in 1996) formal rehearsals had been abandoned, with location recording from Sunday to Monday or Tuesday followed by three days in the studio from Wednesday to Friday, with pre-shooting of complex sequences weeks in advance of their place in the recording rota becoming common practice (Hanson & Kingston 1999: 76-7).

This article considers the implications of these changes through textual analysis. How was the tenor and tone of the series affected by the new modes and forms of production? And how was the way that Coronation Street functioned (and was understood by viewers) as a drama altered by greater scope of location, more characters, new houses and twice as much airtime?

Comparative analysis of the topography of Coronation Street in January 1979 and January 1991

The ten episodes of Coronation Street broadcast in January 1979 operate around a limited number of interior studio locations, all permanent standing sets at Granada Studios. Events are shown in five houses (numbers 1,5, 9, 11 and 13) and four businesses (The Rovers Return, Dawson’s Café, Corner Shop and Kabin newsagent) located either on or adjacent to Coronation Street. Only one other interior studio location is shown, Baldwin’s Casuals, a clothing factory run by and employing many of the programme’s regular characters, formed onscreen of two rooms, a sewing room and adjoining Manager’s Office. Across these nine buildings, events are shown in 14 rooms.

Apart from Coronation Street itself, exterior filming is highly limited, with ‘Greater Weatherfield’ confined to a nightclub doorway on New Year’s Day and the exterior of a block of Council flats Deirdre Langton plans to move into. One episode (#1878) features no filmed inserts whatsoever.

Only one other interior location is used in that month’s run, an unnamed supermarket in Victoria Street featuring as site for a comic storyline in which Suzie Birchall falsely claims to have won an upmarket job as a perfume demonstrator while actually working as a sausage chef. With this plot only running for two episodes (#1879 and #1880) it could only have been practicable and affordable to film these scenes on location, rather than to construct a supermarket set in Granada’s studios. As realised on screen, the effect of recording these sequences on film serves to separate them from the rest of the programme, giving them a different feel and effect. While the convention of 16mm filmed inserts is easy to adjust to when watching exterior scenes (our perception of lighting and acoustics is very different when we step outdoors in real life), the effect is different for the viewer when filmed footage is used for interior scenes, turning the supermarket into a location, visually comprehended as being an other place, as opposed to another place, with different conditions and expectations to studio interiors.

This sense of apartness work in favour of the supermarket plot within the wider dramatic narrative of that month’s Coronation Street. The viewer’s emotional interest in Suzie Birchall’s downfall is reliant upon the possibility of the character being found out and humiliatingly exposed (as inevitably happens when Suzie is seen by gossip Hilda Ogden). When Suzie Birchall’s job is presented in a different, filmic, visual register to the rest of Coronation Street then the prospect of the familiar Coronation Street world encroaching upon her new existence carries a particular disruptive force for the viewer. The sense of mild disjuncture picked up by the viewer in rare sequences like this supermarket storyline worked largely because of the exceptionalism of such locations in the programme at the time, when the wider world of ‘Greater Weatherfield’ was rarely visited.

By the 13 episodes of January 1991 the terrain covered by Coronation Street has greatly expanded, with scenes in eight houses (1, 4, 6, 7, 9, 10a, 13 and 15a) and five businesses (The Rovers Return, corner shop, Kabin, Casey’s Garage and Dawson’s – now renamed Jim’s – Cafe) on or adjacent to the Street. Across these 12 buildings, events are shown in 20 rooms.

The most striking difference between 1979 and 1991 is that flexible location recording now means that much more of the drama occurs away from the street. In addition to many unidentified road and street exteriors, scenes routinely occur in ‘other’ pubs or homes of characters’ girlfriends away from the Street. The relative speed with which location recording could be set up meant that relatively brief scenes requiring outside locations could be shown from multiple perspectives; for example, an argument in a branch of the ‘Wetherfield & General Building Society’ (Episode 3181, 30 January) happening in two rooms of the building. Scenes even happen in Lancashire places identified as beyond Weatherfield (a pub on the A69, a Manchester department store) without being presented as exceptional occurrences.

A major change in the topography of the series is found in the types of workplaces regularly featured. Much of the action is now located in Bettabuys Supermarket, a business which employs (at both junior managerial and more menial levels) several of the Street’s residents, as well as introducing a raft of new semi-regular characters, most notoriously manager Reg Holdsworth, who tends to dominate many viewers’ early ‘90s memories of Coronation Street. Unlike the studio-based Baldwin’s Casuals, Bettabuys was shot on location in a real supermarket, creating a very different sense of workplace to those previously shown in Coronation Street. Where events in Baldwin’s Casuals were confined to the factory floor and manager’s office, action in Bettabuys over the month extends over seven locations; shop floor, manager’s office, canteen, corridors, loading bay, storeroom and ladies’ lavatories.

This range of spaces increases dramatic possibilities for workplace scenes, creating many more opportunities for characters to be seen by, react to, and gossip about, each other. Every room carries different specific social rituals and expectations, that can be observed or disrupted by the people in it; it is taboo for workers to make scenes in front of customers on the shop floor, the canteen between shifts is a better place and time to discuss personal matters, the lavatory is the safest place to retreat to when upset but is also a location where an enemy or boss may overhear you, and so forth. New opportunities created by OB recording for regular settings like Bettabuys maintained the sense of familiarity that viewers had previously found in locations such as Baldwin’s Casuals, but now placed them in the type of verisimiliar ‘outside world’ location previously only seen infrequently and fleetingly in the Street, as in the Suzie Birchall supermarket story of 1979.

An early example of the opportunities that OB location recording created for Coronation Street to tell familiar stories in unfamiliar ways can be found in this episode, written by Paul Abbott. The philandering Mike Baldwin plot is a very typical one (“Mike admits to Alma that he took Dawn out. Alma tells him she loves him but he tells her he’s not after love”), but the scene is located in a beer garden (The Crooked Billet) in a previously-unseen canal-side district of ‘Greater Weatherfield’. The scene is shown through a simple camera set up, with an establishing shot of the leafy sunny pub followed by alternating close-ups of Mike and Alma.

The unfamiliarity and attractiveness of the location raises the dramatic stakes of the scene. Because Mike has taken Alma to a higher class of venue the insensitivity of his actions are made to seem more jarring, and accentuate Alma’s display of disappointment and hurt. What is striking about how this section functions within the dramatic context of the episode’s narrative is that it is an unexceptional, rather brief, dialogue scene of only 80 seconds. Such a scene could not have been attempted under the recording conditions of 1979, where the difficulty and expense of recording in outside locations meant that those few settings that were used had to be dramatically imperative to the story told, as in the supermarket plot. In preceding years, such a scene would of necessity have to be set in a permanent location such as the Rovers or the cafe.

The quick and economic nature of OB recording can also be seen in this episode in a short 40-second sequence in which Alma’s friend Audrey consoles her on a walk in an unnamed park.

The open location, away from home and workplace interiors, allows characters to be reflective about their situation, while also creating a specific sensation of summertime for the viewer, the means to evoke a sense of the passing seasons being something largely missing previously in Coronation Street.

Multi-camera, single camera and editing.

Although there was no one identifiable moment of change in studio recording practice equivalent to the switch to OB exteriors in 1988, incremental changes in the style and form of studio interiors created by changes to camera and editing technology continually occurred during the 1990s. Although studio interiors were recorded on three cameras throughout the 1990s, the introduction of Avid editing technology enabled much easier, and more frequent, post-production of these scenes (Hanson and Kingston, 1999: 100-1). At the same time, changes in camera technology allowed for more sophisticated focusing and higher definition images to be used than before. Here I compare an instance when the tried-and-trusted multi-camera technique inhibited a scene from being fully dramatically realized, with an early use of higher-definition single camera recording in Coronation Street.

Episode 3920 (11 October 1995)

During the three-episode period of the 1990s, the pattern of shooting Coronation Street’s studio interiors required recording up to thirty scenes with three cameras in a day and a half, the director having marked around 400 separate shots on the camera script to be followed during recording, with familiar recognized patterns of camera movement and mixing often regularly used (Kay, 1991: 63). Ostensibly, this episode’s final section should have been ideally suited for recording under such well-established conditions. The scene, an important part of the plot that leads to the exit of one of the programme’s longest running and best-loved figures, Bet Gilroy (nee Lynch) shows a climatic argument and irrevocable falling-out between old friends, material seemingly meat and drink to Coronation Street. Bet has been presented with the opportunity to buy the property and licence of the Rovers Return, which she has previously managed as landlady. Lacking sufficient solo funds for the venture, she believes that her old friend Rita Sullivan will offer finance for the pair to go into managerial partnership together.

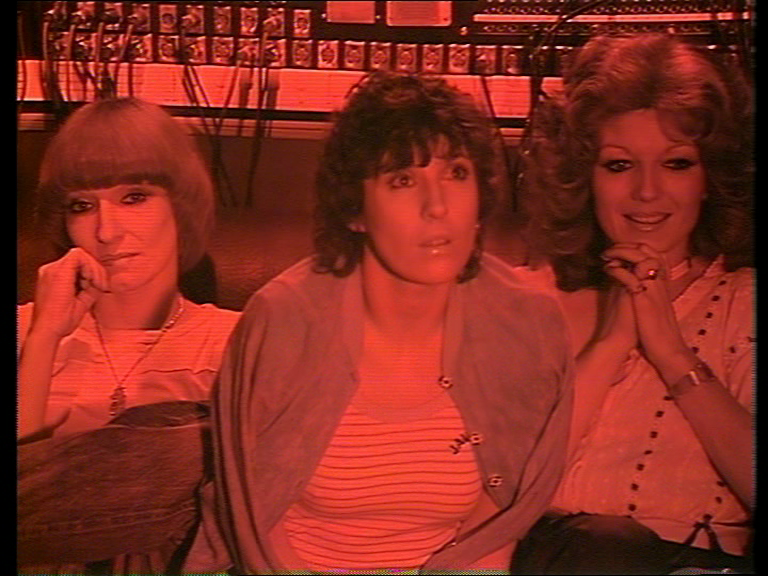

The confrontation, shot on two cameras, in the Kabin newsagent revolves around a very simple rise-and-fall reversal of Bet’s expectations. Rita and Mavis Wilton are working behind the counter when Bet arrives brandishing a bottle of champagne, having secured a reduced price for the pub from the brewery. When Rita tells Bet that she won’t go through with the venture a furious row ensues, with Bet leaving the shop.

This story is presented in very simple visual terms with, once their conversation has started, action confined to a sequence of alternating close-ups of Bet and Rita, book-ended by before-and-after mid-shots of Bet entering the Kabin doorway in triumph and departing in high dudgeon. This clarity of presentation accentuates the combative rhythms of the argument, allowing the viewer to observe the ‘hit’ of reaction to every truth-telling insult (“It was Len’s cash what got you started! But for him, you’d be a clapped-out chorus girl!” “Better than a clapped out barmaid!”) and experience the considerable pleasure of watching the teeth-bearing, gimlet-eyed, fury of two elaborately-coiffured and made-up women in their fifties and sixties in close-up detail.

Unfortunately, this two camera switching also serves to limit the scene from achieving its full dramatic potential. The third woman present during the confrontation, Mavis, ends up being neglected by the camera, leaving her contributions to the scene marginal and incoherent, a blurry and muffled presence in the corner of the frame, briefly hinted at in a momentary sideways glance from Julie Goodyear. Mavis’ contribution to the scene is hard to discern when first watched, and it is only once seen several times (a luxury unavailable to the original viewer) that one can establish precisely what happens to her: she becomes discomfited by the scene, mumbles a suggestion that Bet and Rita might have their discussion somewhere else and, despite being on duty in the shop, walks out in embarrassment. This strand of the story is overlooked in the presentation of the scene, with Mavis seen only as a fluttering hand behind Rita and as the back of a head that momentarily passes in front of Bet.

Unfortunately, this two camera switching also serves to limit the scene from achieving its full dramatic potential. The third woman present during the confrontation, Mavis, ends up being neglected by the camera, leaving her contributions to the scene marginal and incoherent, a blurry and muffled presence in the corner of the frame, briefly hinted at in a momentary sideways glance from Julie Goodyear. Mavis’ contribution to the scene is hard to discern when first watched, and it is only once seen several times (a luxury unavailable to the original viewer) that one can establish precisely what happens to her: she becomes discomfited by the scene, mumbles a suggestion that Bet and Rita might have their discussion somewhere else and, despite being on duty in the shop, walks out in embarrassment. This strand of the story is overlooked in the presentation of the scene, with Mavis seen only as a fluttering hand behind Rita and as the back of a head that momentarily passes in front of Bet.

It is instructive to imagine how this scene might be viewed if performed on a theatrical stage, where an audience would be just as aware of the presence of Mavis as of Bet and Rita, and potentially in sympathy with her: not knowing how to respond when other people are arguing can be as dramatically interesting a situation as an argument itself. Although the possibilities offered by greater use of single-camera technology and the ability to edit in separately-recorded shots would not necessarily alleviate the dramatic faults of this scene (and editing-in separately recorded shots might run the risk of diluting the rhythm of the argument), it would mean that the problem of Mavis’ invisibility during the scene might at least have been more systematically considered before transmission.

In contrast, this episode (directed by Brian Mills) provides an extremely early example of single camera recording and extensive postproduction for studio scenes in Coronation Street. This stylistic experimentation appears to have been born of necessity, with one comic storyline (Rovers landlord Alec Gilroy’s purchase of a rare Mexican mouse-eating spider, which then escapes during a kitchen inspection from an environmental health officer) impossible to record under conventional conditions, with the spider’s performance having to be shot in separate cutaways.

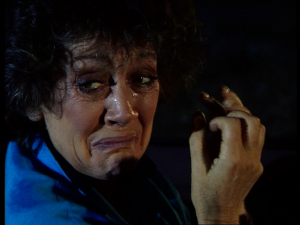

The directorial style necessitated by the nature of the kitchen scenes, which present details and features of the room in close up detail and precise definition, carries over onto other interiors throughout the episode, in which the misfortunes of Ivy Brennan form a tragic counterbalance to the comic story of the spider. Having had his foot amputated after crashing his taxi (in a suicide attempt after Julie broke off their affair), Don is discharged from hospital, but refuses to return to Ivy. Ivy’s vigil of waiting is presented through concentration upon objects in the foreground (a vase of fresh flowers, a silent telephone and a bottle of sherry) while Ivy’s own movements and conversations with her daughter-in-law, Gail, occur in blurred focus in the background of the frame. The striking effect of this unconventional filming demands the viewer’s full attention and, unlike the misdirected “snooping on Don Brennan from the back garden” instance, serves an intentional storytelling purpose. Concentrating upon the objects handled, rather than the woman handling them, encourages empathy with Ivy’s agitation and disconnected state of mind, and is the closest that Coronation Street comes to a point of view shot in this period.

Where this new technique perhaps proves counterproductive is in its jarring ontological unfamiliarity. Were such visual devices used in a one-off ITV drama in 1992 their principle effect upon the viewer would be to offer narrative clarity, but, because they were used in Coronation Street in 1992, a programme that had accrued a familiar visual style through 32 years of studio practice, the direction draws attention to itself as much as to the story, the unfamiliar style distracting the viewer’s attention away from Ivy’s plight as much as it does to illuminate it.

The scene’s style can be described as directorially prescriptive, putting little trust in viewers’ imaginative ability to appreciate nuances of character revealed through the detail of actors’ performances, a traditional Coronation Street strength. When seen from a present-day perspective, the episode (which experiments with sound as well as vision, continuing the soundtrack of one scene over the visuals of the next) appears out-of-time, placing the world of 1992 into the television style of about ten years later.

Plot inflation.

The 1990s broadcasting environment in which Coronation Street operated was a more crowded and competitive field than that of previous decades. As well as the efforts of rival serials Eastenders, Brookside and Emmerdale (Emmerdale Farm until 1989, ITV, Yorkshire Television 1972-, since 1988 broadcast nationwide in an evening slot and continuously throughout the year), television ratings had been falling since the mass availability of the video recorder in the 1980s, and were further challenged by the introduction of U.K. satellite and cable broadcasting in 1989. With soap operas attracting a regular audience to their host channels, all four serials increased output in the 1980s and 1990s, Emmerdale being the last to introduce a third episode in 1997. The increased amount of airtime needing to be filled, combined with the pressure to keep series discussed in the press, has lead to the growth period of soap operas during the 1990s being characterized as a time of greatly increased sensationalism in storylines. Jimmy McGovern (who had written one episode of Coronation Street in 1990), identified and mistrusted this trend:

Inflation has set in. The Street used to be immune to it but even there writers are losing faith in actors, and the actors are losing faith in the characters. So people have to place great faith in the stories. But that’s when inflation sets in because one story has to top another. (In Jeffries: 2000, 170-1)

To suggest that Coronation Street had somehow avoided sensational storylines before the late 1980s would be a misrepresentation. The recurrent need, faced by all continuous series, to write actors out necessitates the regular recurrence of partners walking out of relationships and sudden deaths and, although the Street didn’t suffer its first murder until the shooting of Ernest Bishop in 1978, its unfortunate residents had already experienced many shocking demises; crushed by van, suicide, or electrocution by faulty hairdryer. Nor had it avoided spectacular disasters, enduring a train crash in 1967 and a lorry crash in 1979. The particular change to Coronation Street in the 1990s lay in the form that such occurrences took, as well as the frequency with which they happened. Previous shocking events, such as Minnie Caldwell being held at gunpoint (1970), or Deidre Langton being sexually assaulted (1977), had always occurred in the familiar location of Coronation Street itself, with the sense of community that viewers derived from the setting helping to make such exceptional storylines disruptive and memorable, encouraging empathetic feeling for regular characters who had become victims.

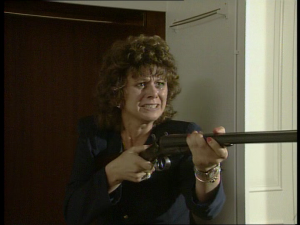

An early example of how the presentation of potentially sensational violent events in Coronation Street was changing is the end (a week after the wedding) of Mike Baldwin’s second marriage (#3251, 12 July 1991). When Jackie, a wealthy widow, discovers the full extent that Mike has attempted to defraud her through matrimony, she threatens him with a loaded shotgun when he arrives home. Although this violent scene would be always freighted with the problem of basic implausibility wherever it was set, the unfamiliar ‘Greater Weatherfield’ location of Elmsgate Gardens handicaps its ontological integration into the imaginative world of Coronation Street. The location (a real house, not a studio set) has only been previously seen in a handful of episodes and carries few emotional associations for the viewer, so such a violent event carries less in the way of disruptive force for the viewer than it otherwise could: people might do such things all the time in Elmsgate Gardens, for all that the regular viewer knows. When such sensational events happen away from the understood community of Coronation Street, audiences can view them as separate from other incidents in the programme, and they come to carry less of an emotive pull.

By 1997, spectacular and shocking events had become almost commonplace in the now four-times weekly Coronation Street, realised on such a grand scale as to make makes the gun-toting Jackie Baldwin sequence of six years earlier appear brief and underplayed in comparison. Advances in PSC (Portable Single Camera) technology and a more flexible recording schedule allowing greater leeway for storylines to be shot out of sequence made it more possible to mount ambitious scenes on a scale rarely previously attempted.

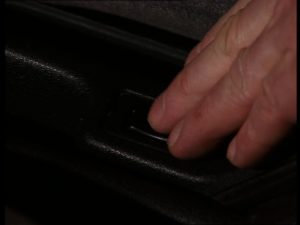

The events of this hour-long special (double-length editions were an innovation first introduced in 1995), present a good example of this in practice. The episode concentrates upon the actions of a crazed Don Brennan, who has contrived a vendetta against Mike Baldwin and recently set fire to his factory. He picks Alma (now Mike’s third wife) up in his (unlicensed) taxi one night, drives past her requested stop, locks her in, and refuses to let her leave. At a deserted quayside, Alma tries to call for help on the taxi radio, which Don then rips out and destroys. After Don hits her Alma breaks free, but Don chases her in the car and forces her back into the cab. He drives the taxi straight into the River Irwell at the Quays, with them both inside it.

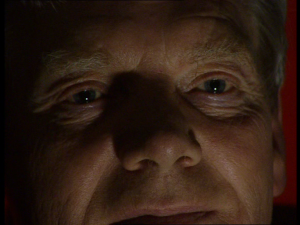

This vivid storyline comprised the most elaborate and technically demanding sequence yet attempted in Coronation Street, requiring five separate 12-hour night shoots involving trained stunt people and underwater filming, a process compared by Coronation Street’s producer to making a James Bond film (Hanson and Kingston, 1999: 94-5). The use of PSC editing does give the story a cinematic feel, facilitating extreme close-ups of Brennan’s eyes reflected in the rear-view mirror, quick editing of spectacular dangerous driving, shots rotating around the ragged couple on the deserted quayside, POV shots of the driver stalking his quarry, and so forth.

The same token that makes this storyline spectacular also makes its integration into the world of Coronation Street problematic. The Don and Alma plot forms 15 separate sections within the episode, some of these very brief. Each time that the action returns from the frightening wastelands of Greater Weatherfield back to the Street, the viewer is forced to readjust to a different, ontologically familiar, world. Although this juxtaposition of Rovers Return and terrifying Quayside ordeal is freighted with dramatic ironies it tends to dominate the overall narrative of the episode and means that more subdued plots, such as the recently widowed Mavis’ grief, are given less room to establish themselves than might otherwise be the case. While it was impressive that Coronation Street was capable of achieving a convincing thriller kidnap plot in 1997, similar plots could be seen in other drama programmes at the time, and such stories prevented Coronation Street from creating distinctive drama unique to itself.

The place of this story within the wider narrative of 1997 Coronation Street also demonstrates the questionable sustainability of a series in thrall to plot inflation. Kidnapping Alma (following on from setting fire to Baldwin’s factory) wasn’t the climax of Don’s irrational behaviour, which eventually arrived six months later when, having been interrupted while attempting to club Mike to death, Don died, while attempting to run Mike over, in an explosive car crash (#4278, 8 October 1997). Spectacularly violent events risk becoming less of a talking point once they become regular occurrences.

Conclusion

This article has demonstrated that two concurrent changes that Coronation Street underwent at the end of the 1980s (greater and more extensive location recording and the introduction of a third episode) radically affected the form that the programme took, and how viewers understood it.

The greater amount of airtime to fill encouraged the creation of more sensational and protracted storylines. In the 1990s, the world of Coronation Street expanded beyond the immediate confines of the Street into ‘Greater Weatherfield’, a place that bore more visual similarities to the wider world, but which undermined the emotional and imaginative ties that viewers had formed with the familiar Street itself.

POSTSCRIPT (2 October 2013).

Some enjoyably trenchant comments about plot inflation from Christine Geraghty are included in an article about the crisis in British soap operas by Stuart Jeffries in today’s Guardian:

Of course, soaps have hardly been popular because they have their finger on the pulse of the nation. In their heyday, they were immersive experiences that took their own sweet time developing stories and characters, and thereby made themselves convincing and seductive to mass audiences. “People witter on about The Wire and Mad Men,” says soap opera specialist Professor Christine Geraghty of the University of Glasgow. “It drives me mad. British soaps were doing those complicated multi-layered narratives long before HBO was invented. Soaps used to have the confidence to let very little happen sometimes.”

Soaps, then, were like Greek drama. What was important was not splashy plot twists – be it car crash, baby swap, lesbian snog or corpse under the patio – but how characters processed such incidents through the medium of gossip. “They don’t have the confidence to do that now,” says Geraghty. “There’s a relentless intensity of plotting that makes soaps often seem daft.” Why are they doing that? “Because the big stories capture the intermittent viewer, often at the expense of the regular viewer. The logic is that the more stories you have and the bigger they are, the better you compete with other formats. But that relentlessness eats up people and stories in an effort to counteract what’s going on elsewhere in TV. The risk is they look soulless and cynical. It’s also a vexed question as to whether those big stories help ratings in the long run.”

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hanson, David and Kingston, Jo. Coronation St.: Access All Areas. London: Andre Deutsch, 1999.

Jeffries, Stuart. Mrs Slocombe’s Pussy: Growing Up in Front of the Telly. London: Flamingo, 2000.

Kay, Graeme. Life in the Street: Coronation Street Past and Present. London: Boxtree, 1991.

Kibble-White, Jack. ‘Everyday Folk and Inflation’, ( http://www.offthetelly.co.uk/?page_id=276 ), 2000.

Little, Daran. 40 Years of Coronation Street. London: Andre Deutsch, 2000.

Podmore, Bill and Reece, Peter. Coronation Street: The Inside Story. London: Macdonald, 1990.