Dr Matthew Nicholls from the Department of Classics at the University of Reading is interested in the political and social history of the Romans and the way that the built environments of Rome and cities around the empire expressed their values and priorities.

Matthew has an interest in computer modelling as a way of exploring ancient structures and bringing them to life and has developed an ambitious recreation of the city of Rome in the age of Constantine.

The first Roman emperor Augustus (ruled 31BC – AD14) began the imperial tradition of offering the people of Rome the ‘bread and circuses’ – cheap food and entertainment on a lavish scale – that came to characterise life in the city.

Augustus, as one ancient commentator tells us, “surpassed all his predecessors in the number, variety and splendour of his games”, often using new or restored buildings within the city as a setting and boasting (not without justification) that he had “found Rome a city of brick, and left it a city of marble”, a tangible element of his vision for cultural, political and moral renewal of the Roman state.

After more than a decade in power Augustus used this renewed city as the setting for a particularly splendid set of games, which combined high literary culture and deliberately archaising religious ceremonial with popular gestures, including the provision of plays and chariot races. These games were intended to celebrate a renewed epoch of Roman prosperity and divine favour, a saeculum, and are therefore known in English (despite their religious function) as the Secular Games of 17BC.

We know about these games from a variety of sources – ancient authors mention them, the special hymn that the poet Horace wrote at the emperor’s behest survives, and several of the buildings or areas used for the events are known to archaeologists. We also have an inscription, found in fragments, that had been reset into a medieval wall, which lays out the daily programme for the games as devised by the priestly board in charge with details of the venue, date, and time for each event.

Combining the text of this inscription with what we know about Augustus’ building programme in Rome lets us see how he used his regenerated city as a backdrop for these games, reinforcing the message of renewal and prosperity with a splendid vista of new and restored buildings. In particular, the daily programme of supplementary entertainments, put on as crowd-pleasers for a week after the main religious sacrifices had been concluded, led crowds of spectators in their tens of thousands from open ground on the edge of town past a series of buildings – temples, porticoes, theatres, squares, and parkland – that had received special attention in the previous decade, showing off a thoroughly regenerated quarter of the city.

The modern Olympic Games, with their simultaneous functions as national showcases, catalysts for urban regeneration, and cultural spectaculars, offer a good comparison.

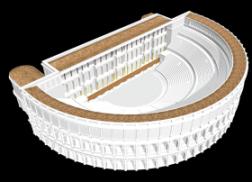

Moreover, the detailed timetable set out in the inscription allows us to investigate how the Games’ planners took particular advantage of the summer sun. The Games were held in early June, with events starting (as was common in the ancient world) shortly after sunrise. By the time that spectators arrived at the morning’s final venue, Augustus’ own new Theatre of Marcellus, it would have been around a quarter past eight in the morning on a modern clock. The Theatre of Marcellus is, uniquely for theatre buildings in Rome, orientated so the stage points north east; the other venues for the Games point west. With help from a UROP undergraduate research assistant, Ed Howkins, I used the digital model of ancient Rome that I have been building as a research and teaching tool to investigate the lighting conditions in the Theatre of Marcellus at the relevant date and time.

It turns out that the stage would have been perfectly illuminated for exactly the period in which the plays were held there, with the sun shining on the actors rather than into the faces of the spectators. It seems that Augustus’ theatre architects had created a venue intended especially for morning performances, and that his games planners responded to this by ensuring that each day’s entertainment culminated in the splendid new theatre at just the point when it was most perfectly illuminated – a subtle reminder that the reign of Augustus and the continued prosperity of Rome were, as the prayers for the Games implied, cosmically ordained and favoured by heaven.