TPR to the South East of Brazil: Je Landscape Palaeo fieldtrip

It is not long since I came back from the Jê landscapes Project field trip in the South east of Brazil.

The experience was truly fantastic. I had the pleasure to meet and know incredible landscapes and generous people. As a result we found fantastic sites and collected what we believe are the best representative materials for our project.

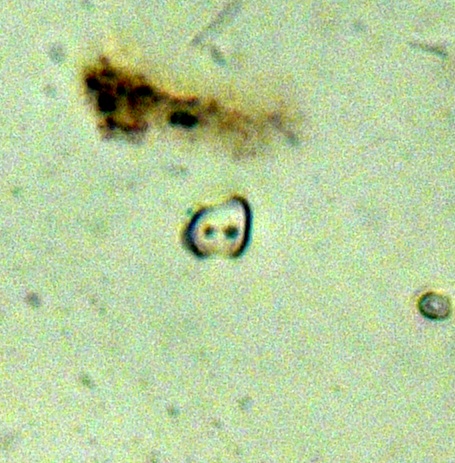

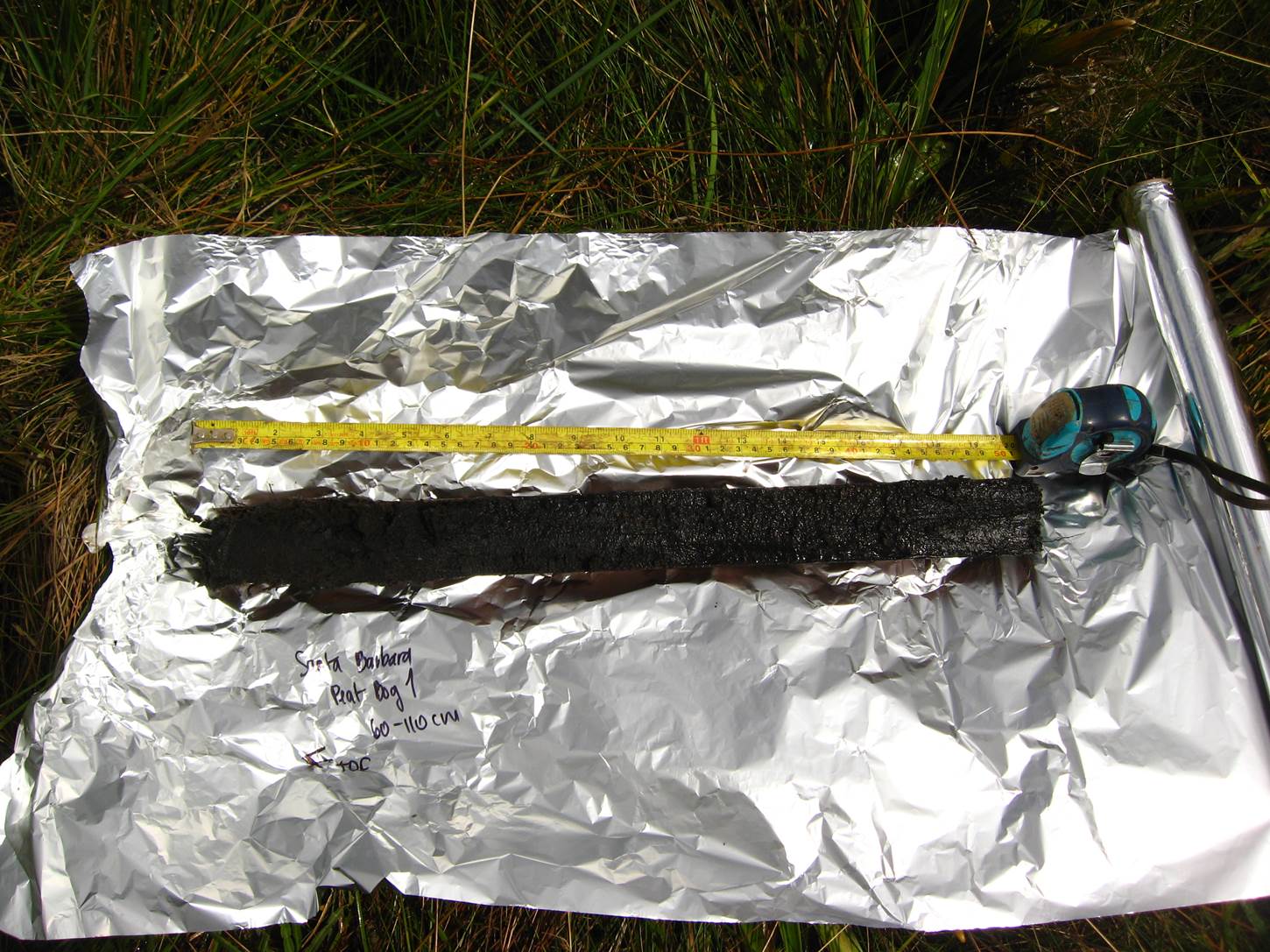

Focusing in the vegetational, environmental and climate reconstruction during the existence of the Proto- Jê culture, the aim of the field trip was to collect sediments from bogs at the main three geographical areas where the project is studying the Jê culture: Urubici (Highlands), Rio Fortuna (were the Atlantic forest is) and Campo Belo do Sul (Highlands). Armed with dutch gauge and Russian corer, me and my fantastic assistant Álvaro Costa toured over 200 kilometres within Santa Catarina region looking for deep bañados.

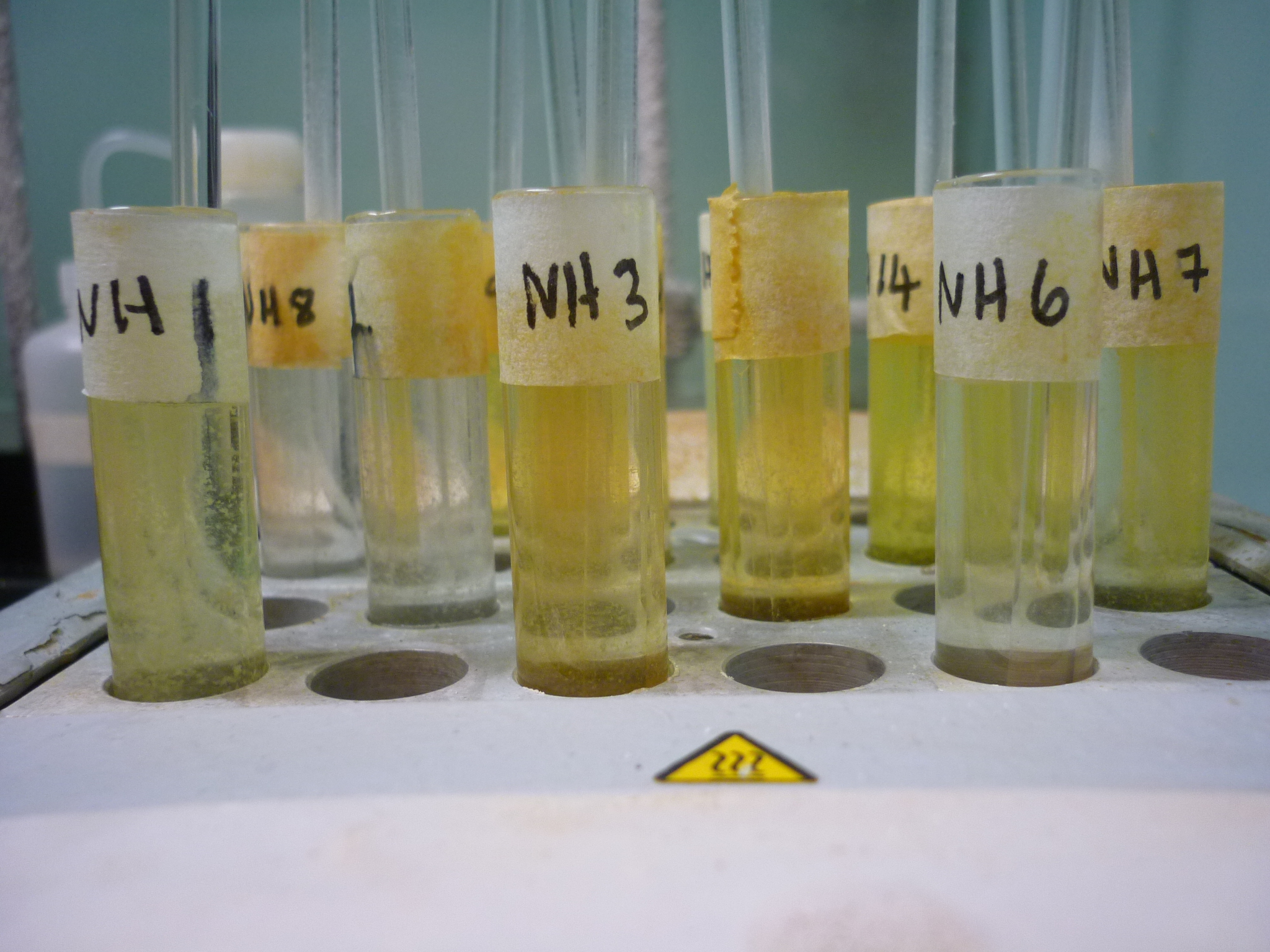

Our experience in Urubici started very challenging. The very first bog we tried coring was what I would say the most difficult of the whole trip. We simply couldn’t extrude it. It was a clay and silt grey sediments with a large proportion of silica that would stick to the inside of the Russian corer like leeches, and not even using spatulas to do toggle we could extrude them. Long story short, we managed to find a way to extrude without disturbing the sediments and from that moment onward nobody stopped us. We cored 13 sites within the area, all with overlapping and duplicate drives.

Our experience in Rio Fortuna, towards the littoral side of Santa Catarina, was indeed a very different but not an easier landscape to core. To find a bog that didn’t suffer the consequences of agriculture or cattle, or that wasn’t converted in a fish tank to grow trout was the first but not only barrier; being able to cut across with the Russian corer the dry and sandy sediments was another one. We would not give up, and using as much of our patience as well as our weight to push we recovered sediments from four sites very close (~100m) to archaeological finds.

Campo Belo do Sul gave us a little truce. Thanks to Frank Mayle, who already went to the area in April 2014 and cored eight fantastic sites, we weren’t in much need to core much more. I personally enjoyed this part of the field by joining to the archaeological team that was in the site excavating Abreu e Garcia (funerary) and Baggio (oversized pit-house) sites. An army of students, plus researchers Dr Mark Robinson, Dr Rafael Corteletti, PI Professor Jose Iriarte, PhD students Jonas Gregorio and Priscila Ulguim and of course, loads of yerba mate there were many hours of tireless digging.

Another fruitful stop was in Gateados farm, a timber company committed to preserve and protect native vegetation. With the crucial help of Professor Lauri Schorn and his student Alyne Rugiero from University of Blumenau, we collected moss pollsters from the most pristine Araucaria forests available in the area. We will use the pollen rain contained in these natural traps to understand how modern Araucaria forest vegetation expresses in the pollen record.

It was almost two very intense months of travelling, coring and falling, but I would definitely do it again. Now the next step is face the many hours of work in the field translated in sediments to unveil what the past of vegetation and climate was like when Jê culture inhabited these areas.

Almost forgot… I also found mosquitos…

Post by Macarena

@DrMacarenaLC

Dr Jonathan Mitchley un-puzzling students with modern plant material

Dr Jonathan Mitchley un-puzzling students with modern plant material