If you’ve ever bought an avocado, you’ll know it’s one of those fruits which seems to take forever to ripen. Botanically, the fruit of the avocado is actually a berry with a single (very large) seed. Both of these facts are connected to an interesting evolutionary relationship….

A massive berry which won’t ripen till it falls off

The avocado, botanical name Persea americana Mill., is a rapidly growing tree or shrub, and mature ones can reach up to 20m. The one we have in the tropical greenhouse (pictured above) is a baby, and doesn’t have fruit yet. The reason the fruit takes a week or two to ripen is that although it matures on the tree, it won’t ripen until it’s removed (or falls off), apparently due to an inhibitor in the fruit stem. This is handy because the fruit can be left on the plant as a method of storage. But of course this isn’t the reason why this trait evolved! And what about that massive seed?

Persea americana fruit. Tree growing in Mexico.

Photo by Alejandro Barrientos Priego http://www.avocadosource.com/slides/20040328/005087s.htm

One theory is that these traits evolved as an adaptation to extinct megaherbivore dispersers, which were around before the Pleistocene extinction (13000 years ago). The fallen fruit ripening on the ground was eaten whole, for example by a giant ground sloth, and the undamaged seed was egested somewhere else, thus being effectively dispersed with it’s own little pile of fertiliser. No native extant animal is large enough to effectively disperse avocado seeds in this way. More on this and other ‘evolutionary anachronisms’ in this article from the Smithsonian Magazine.

Human dispersers

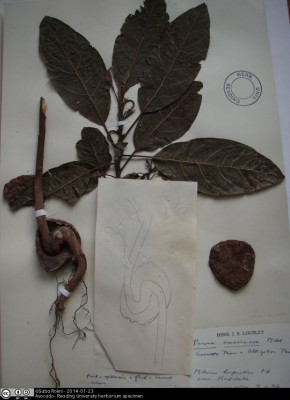

Though not cultivated in the UK, this specimen (which you can find in the University of Reading herbarium) was found growing wild near Rochdale.

Despite being an anachronism, P. americana is doing very well due to its human dispersers. Persea species probably originated in Mexico and Central America, in upland montane cloud-forests and the lower slopes of rainforests. Avocados were probably first cultivated about 8000 BC, at high altitudes in Mexico and Guatemala, but there is evidence of their being eaten as wild fruit before then, the oldest archaeological record is from Coxcatlan, Mexico, from about 10,000 BC.

The Conquistadors found avocados growing in a range of environments from Mexico to Peru and, as is the case for so many other crops, are responsible for introducing avocado to the wider world. An interesting fact is that they wrote many of their documents with an indelible ink made from avocado seeds.

Another nice specimen from the Reading herbarium. Impressive that they managed to press and dry the fruit as well!

As a crop, avocado is only semi-domesticated, and it’s only over the last 150 years or so that it has become a commercial, international crop, mainly through work pioneered in California and Florida. Nowadays, it’s grown commercially all over the world including the US, tropical America, larger islands of the Caribbean, Polynesia, Philippines, Australia, New Zealand, Madagascar, Southern Europe, North Africa, South Africa, Israel, and Australia.

Names

This avocado growing in cloud forest in Nicaragua is a particularly good example of where the inspiration for its name came from!

The name ‘avocado’ originates from the Spanish ‘aguacate’ from the native Mexican Nahuatl word ‘ahuacatl’, meaning testicle. Look at the adjacent picture and you can probably see why! Incidentally, the word ‘guacamole’ comes from ‘Ahuaca-mulli’, which is Nahuatl for avocado sauce.

Thank you Sainsbury’s

In the U.K., avocados became widely available in the 1960s when they were introduced by Sainsbury’s supermarket as ‘Avocado Pear’. During the last 10 years, avocado consumption has increased substantially throughout the world, though Latin America still has the highest consumption in the world. This may in part be due to its status as a ‘super-food’. Though many things are given this label, I think in the case of avocado it may be well deserved. It’s a very nutritious and calorific fruit, but not high in sugars. It’s rich in vitamins, iron, minerals and protein, and of course monounsaturated oils, only matched by the olive.

Avocado Milkshake?

In Spanish speaking countries, and in the U.K., avocado’s are thought of as savoury, but in Portuguese speaking countries and several other countries around the world they’re thought of more as a dessert ingredient. Various drinks seem especially popular. You may have heard of Advocaat, the sweet liqueur, which was made in the past by Dutch populations in Suriname and Brazil. Sadly, it’s now made in the Netherlands and uses egg yolks in place of avocados. But other avocado drinks are still popular; in the Philippines, Brazil, Indonesia, Vietnam and Southern India, avocados are combined with condensed milk and ice and blended into milkshakes, sometimes also blended with coffee. In Ethiopia they’re mixed with sugar and milk, usually served with Vimto and a slice of lemon. If you feel inspired, there’s a demonstration from Youtube below.

Some varieties of avocado grown in Mexico have leaves with a strong anise scent, and these are used as a spice. Very rarely, the fruits themselves taste of anise. For reasons related to the word’s origin, and the shape of the fruit, the avocado is also considered an aphrodisiac or fertility food. Louis the XIV believed it restored his lagging libido. Also avocado oil is high in vitamin E, and has high skin penetration and rapid absorption, so is often used in face masks and creams.

Avocado Flowering

Leaves of P. americana; simple, entire leaves, becoming tough and leathery (darker leaves at the back), and with an aroma when crushed. This is one of the features of the Lauraceae.

On a more scientific note, P. americana is a model species for cutting-edge genomic research, and is used to aid in understanding the evolution of angiosperm flowers from gymnosperms. This is because P.americana is a member of the laurel family (which also includes Bay Laurel and Cinnamon), the Lauraceae . This is a basal lineage near the origin of the flowering plants; the earliest ancestors recognised as members of Lauraceae are believed to have evolved about 65 million years ago.

P.americana has small, inconspicuous, greenish coloured flowers which are adapted to pollination by small insects. Under favourable conditions, each flower opens twice over a 24hr period, firstly as functionally female, and secondly as functionally male. This favours cross-pollination, but with a fail-safe mechanism ensuring some self-pollination in most situations.

European honey bee visiting an avocado flower.

Photo by Gad Ish-Am: http://avocadosource.com/slides/20040411/006017s.htm

Avocado Diversity

Persea americana var. americana. Variation in fruit. Photo by Alejandro Barrientos Priego: http://www.avocadosource.com/slides/20040328/005083s.htm

The genus Persea contains about 200 species, with many wild populations. P.americana is a very diverse and polymorphic species containing several taxa. Lacking a really comprehensive study, at present there is no consensus regarding the relationships between these taxa and how they should be classified. There are generally considered to be three putative botanical varieties within P.americana: var. americana, var. drymifolia and var. nubigena. Differences between them relate primarily to ecological preferences and fruit characteristics, though even within the same botanical variety the size, shape, rind, flesh and seed of the fruit is highly variable. Variability in seed size is very common even within the same plant.

Tiny avocado fruit, Coatepec Harinas, Mexico. Photo by Alejandro Barrientos Priego: http://www.avocadosource.com/slides/20040328/005093s.htm

About 220 cultivars of P.americana are known, these are decended from all three P.americana varieties and their hybrids, most of them are not widely grown. ‘Fuerte’ and ‘Hass’ are the most common. Hass now accounts for 80% of cultivated avocados in the world, and is a clone from a single tree raised by Rudolph Hass of California, which he patented in 1935.

Local avocado fruits. San Cristobal de las Casas market, Chiapas, Mexico. Photo by Alejandro Barrientos Priego:

http://www.avocadosource.com/slides/20040328/005100s.htm

Avocado diversity is threatened by market demands for the ‘Hass’ cultivar. This cultivar has replaced avocados in cultivation in the Americas. Furthermore, the global trade of ‘Hass’ undermines the marketability of locally produced cultivars. Of particular concern is the replacement of more diverse plantings of seedling avocados throughout Meso-America.

While avocado has entered, and become popular, in the international market we see a consequent decline in diversity of avocados and threat to the natural gene pool.

References

Chanderbali, A.S. (2009). Neotropical Lauraceae. In: Milliken, W., Klitgård, B. & Baracat, A. (2009 onwards), Neotropikey – Interactive key and information resources for Fowering plants of the Neotropics. [Accessed 13.12.13]

Gaillard, J.P., and Godefroy, J. (1995). Avocado. Macmillan Education Ltd.

Heywood, V.H., Brummitt, R. K., Culham, A., and Seberg, O. (2007). Flowering Plant Families of the World. Firefly Books: Ontario, Canada. pp. 182-183.

Morton, J. (1987). Avocado. In: Morton, J., Fruits of warm climates. Julia F. Morton, Miami, FL. pp. 91–102. [Accessed 13.12.13]

Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (2013). Persea americana (avocado). [Accessed 13.12.13]

Smith, K.A. (2013).Why the Avocado Should Have Gone the Way of the Dodo. Smithsonian Magazine. The Smithsonian. [Accessed 13.12.13]

The Hofshi Foundation (2014). Avocadosource.com. [Accessed 14.1.14]

USDA, ARS, National Genetic Resources Program. Germplasm Resources Information Network – (GRIN) [Online Database].National Germplasm Resources Laboratory, Beltsville, Maryland. [Accessed 27.12.13]

Whiley, A.W., Shaffer, B., and Wolstenholme, B.N., (eds) (2013). The Avocado: Botany, Production and Uses. 2nd edition. CABI Publishing.

Images re-used from www.avocadosource.com are © 2003-2014 The Hofshi Foundation and restricted to personal use.

هناك الكثير من الطرق الشائعه حول اسرع طرق لانقاص الوزن الزائد ولاكن يجب ان نعلم ما هي انواع الدايت والفوائد المهمه التي تساعد في خساره الوزن وخساره الدهون والحصول علي حياه صحيه ولاكن تاتي خساره الوزن هي من اوليات النظام الغزائي واولويتك شخصيا وهنا تتعلم حول كيفيه الحصول علي الوزن المثالي

https://www.zsporte.com/2022/02/blog-post_23.html