Written by Adam Koszary, Project Officer.

If you’ve been on the internet for the past few days then you may have heard about the mouse which died in our Victorian mousetrap.

We are very pleased and a little surprised to have gone viral, and since our original blog post have some updates on our rodent friend. For one thing, we think that the mouse is a she. Our conservator believes that she was trying to build a nest and while nibbling the label on the trap, the string attaching it to the object fell inside. Chasing the string, the mouse found itself trapped.

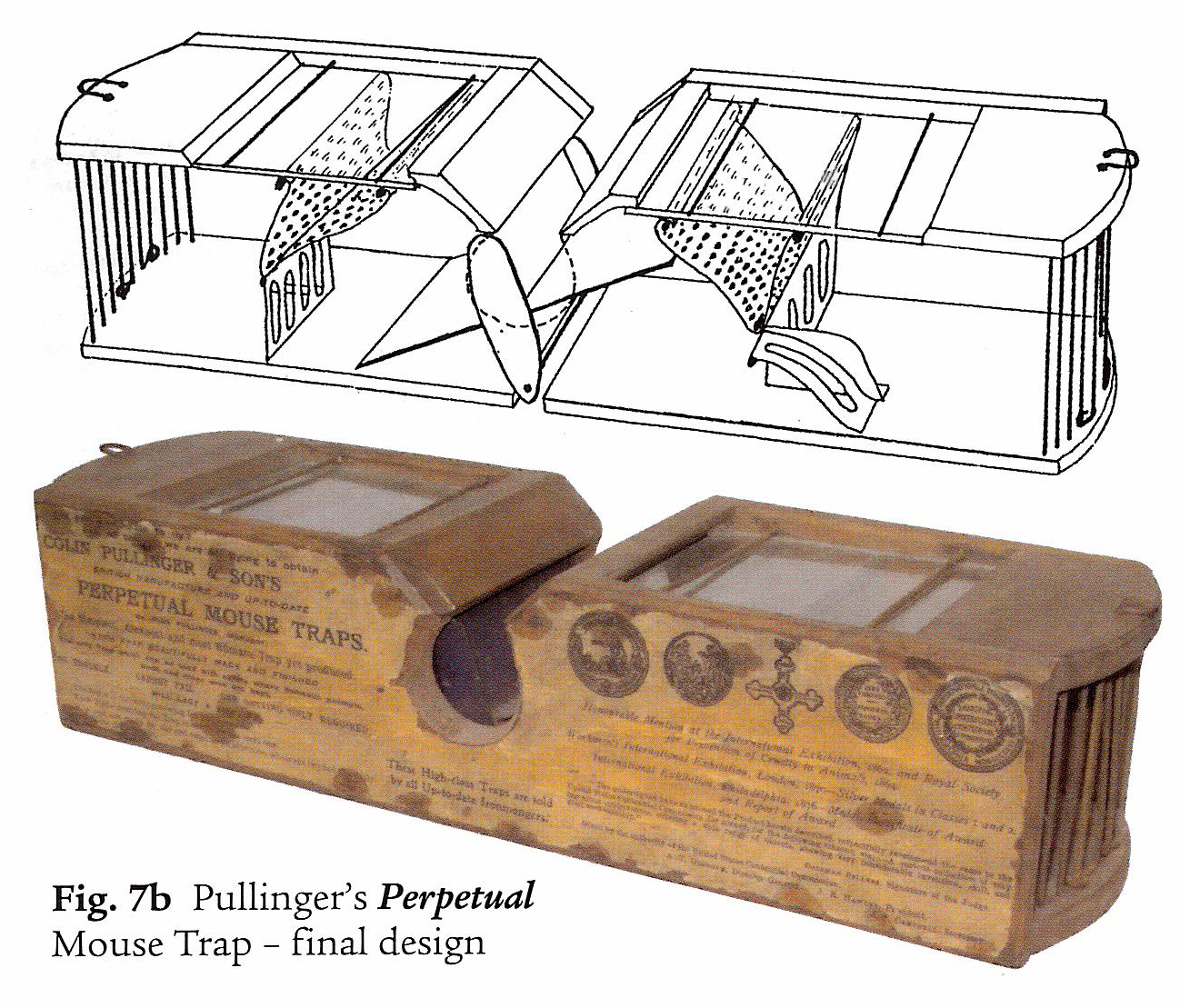

David Drummond, who donated his collection of traps to the Museum, provides this diagram of the trap in his 2008 book, ‘British Mouse Traps and their makers’, 2008.

The trap itself operates by a see-saw mechanism in its middle, which allows a mouse to enter the trap but then finds the door has swung shut on it. The owner of the humane trap would then release the mouse afterward. As we don’t expect these traps to be working as mousetraps we don’t tend to check them regularly, hence the fact that the mouse sadly perished in this instance.

Its inventor Colin Pullinger operated what he called the ‘Inventive Factory’, which is where he designed his first commercial success, the Perpetual Mouse Trap. During his most productive period in the 1880s his staff of around 40 men and boys churned out 960 traps a week.

Pullinger’s presence in his hometown of Selsey is denoted by a blue plaque, but now his reputation has experienced a new boost, with many people online praising the effectiveness of his trap in the modern age.

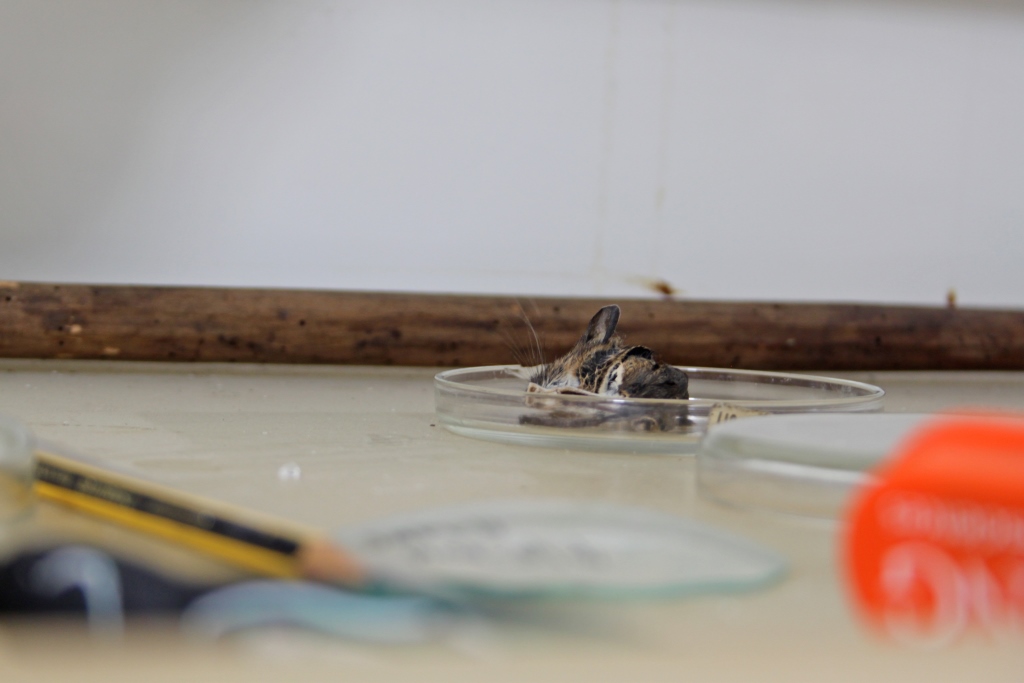

In our previous post we were undecided on what to do with the mouse, but we have now decided to preserve it. The mouse was giving off quite a stink, which suggests that her death was fairly recent, and so was fumigated by our Conservator.

For now, her body rests in a small, tissue-paper tray surrounded by silica gel in a sealed plastic box. The silica gel will dry out the mouse and make it safe for display in our new galleries. The Museum is about to begin constructing our new exhibitions, and it’s safe to say that this mouse will be front and centre.

And for those who have smelled a rat, we can categorically deny that we planted the mouse in the trap in order to gain this publicity. Not only does it go against every rule in Conservation and museum ethics, we don’t think any of our staff are Machiavellian enough to have pulled it off.

For an insight into why this mouse trap went viral, check back tomorrow for another blog post.

“Build a better mouse trap and the world will beat a path to your door”……

At least mice. So it is said.

A very clever and interesting design. It seems that the trap is bi-model, designed to have a second mouse enter later and reset the trap for the opposite side. The trap could have been a single action, with mice being caught in a single compartment.

Another successful design from the past was a barrel of water with a trick lid. The lid contained a circular trap door. When the mouse put his full weight on the door, it suddenly opened down, and the mouse fell into the water to drown. The circular trap door re-closed automatically by a spring when the mouse’s weight was removed.

A third successful design is based on the lobster trap. A lobster trap contains a funnel of decreasing diameter. As the lobsters crawls along the funnel, they scrunch down to fit the funnel until they exit the funnel inside the trap. Once inside, the lobster’s tiny brain does not permit it to find and navigate the small funnel entrance to escape.

If the funnel is replaced by a collapsible net, a mouse will readily push his way through the net, exiting inside the trap. Once inside, the mouse’s mammalian brain cannot solve the problem of finding the net opening from the inside, since the net has collapsed after the mouse exited the net inside the trap.

Personally a bucket of good ol water 1/2 full does the trick ! They will never bother you again guaranteed !

P.S. Just place bucket in open site of em.

cool