Volunteer, Whitney continues her series of interviews with members of staff with a chat with Jacqueline Winston-Silk, Art Collections Officer, about her role.

Can you give me a little background of the work you do here at MERL?

I am based at the Museum and employed by the University of Reading. I manage the University’s Art Collections as a whole and I am also responsible for artworks that are held at MERL and within Special Collections.

What are your main responsibilities?

Managing and advocating for the University’s Art Collections. Developing the collections and making artworks accessible and relevant to students, academics and the public. I also have to think strategically in terms of exploiting the Art Collections to provide value and research potential for the University.

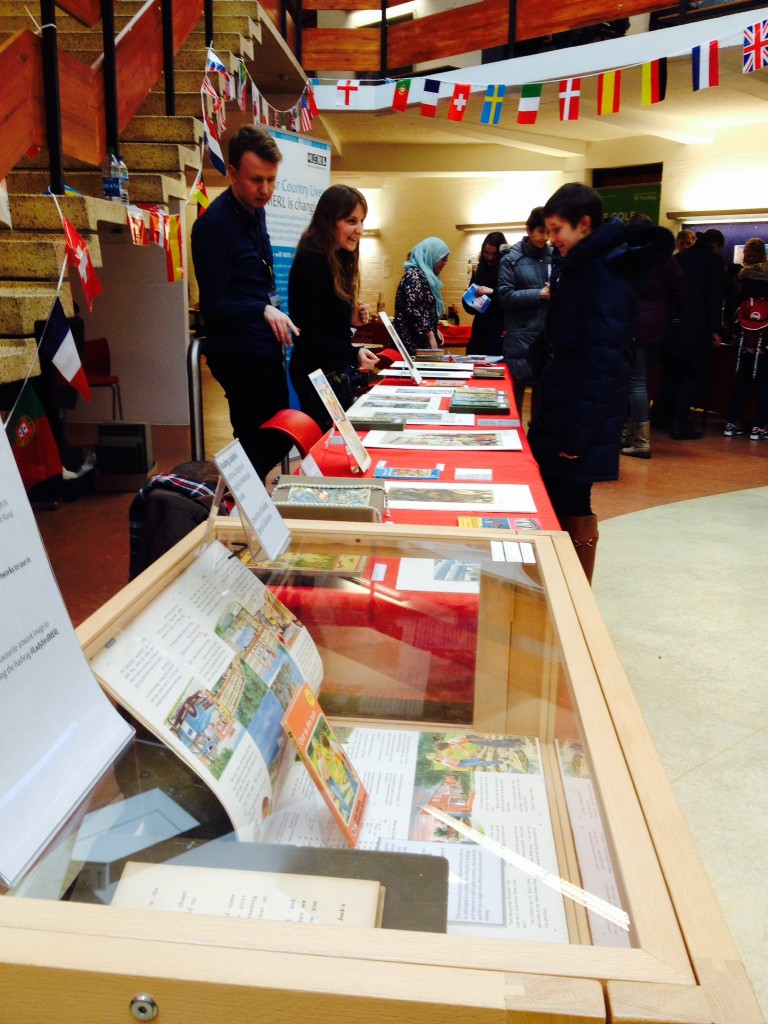

Historically, no one has held the single responsibility for the Art Collections. Because of this I feel the collections have not been used to their full potential. The majority of our students and visitors may not be aware of the extent of the art collections because we do not currently have an online collections database to search – like there is for other University of Reading collections. Therefore, to address the identity and visibility of the Art Collections we are embarking on a collections audit. Our aim is to research, digitise and catalogue the entire collection. Ultimately, it is a process of establishing what we have and where it is! As we do this, we can increase the ways our audiences gain knowledge and enjoyment from the collections – whether within teaching and learning, or through programmes of displays and events.

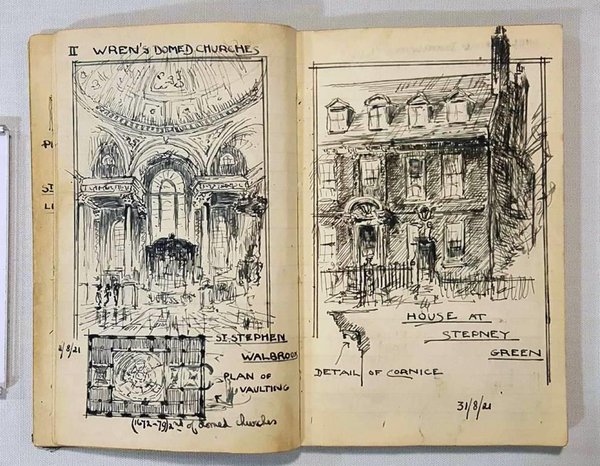

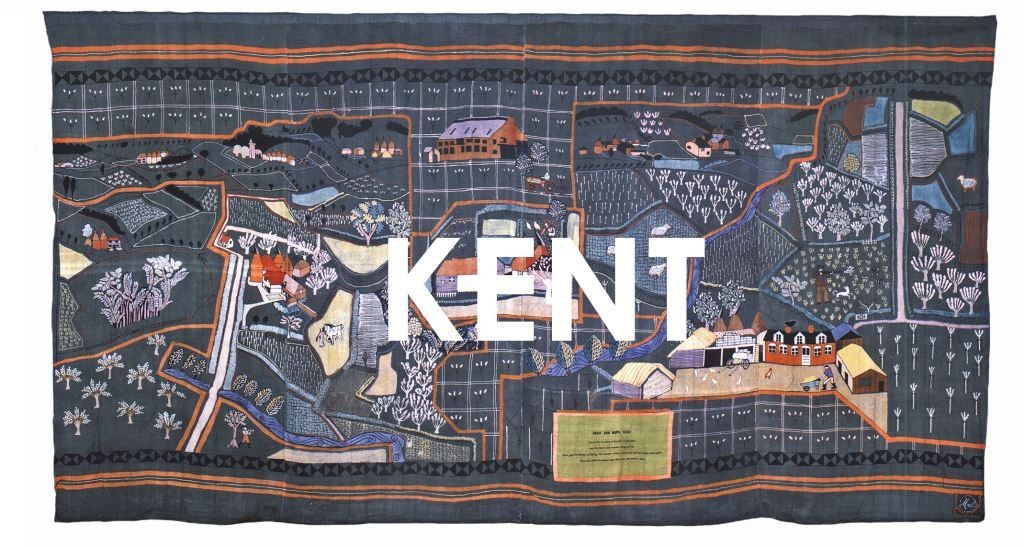

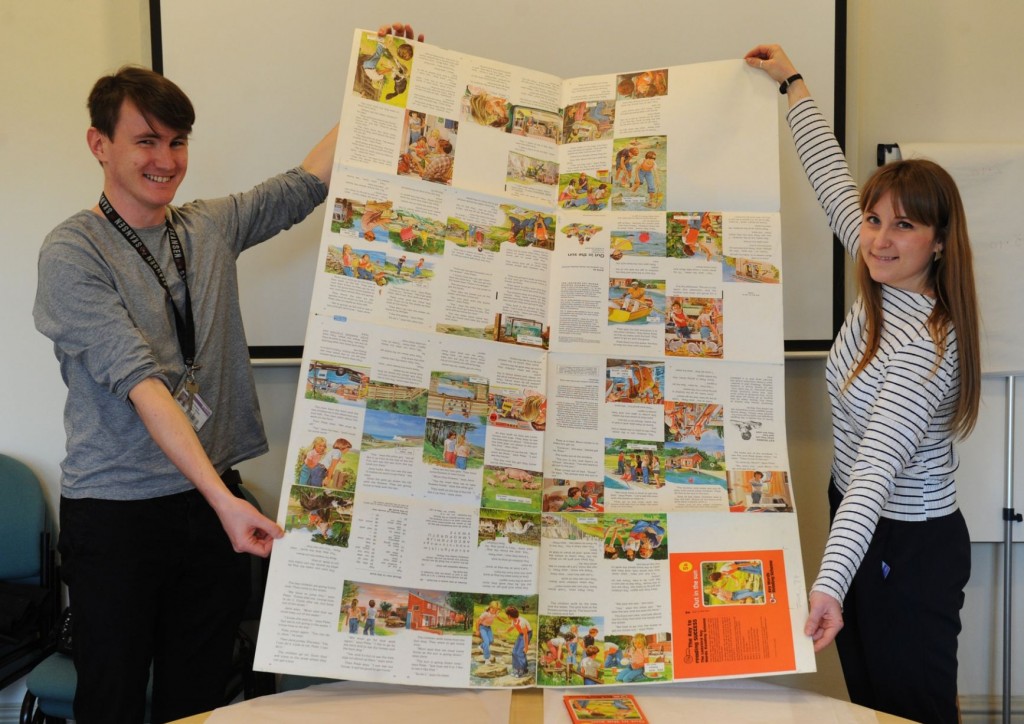

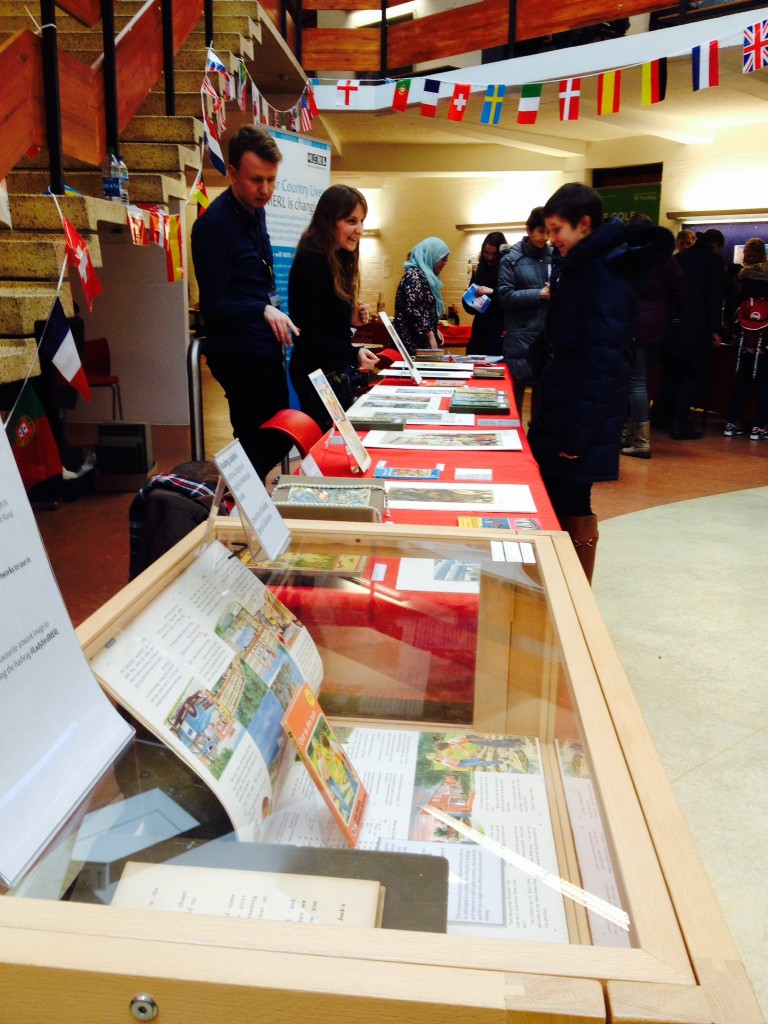

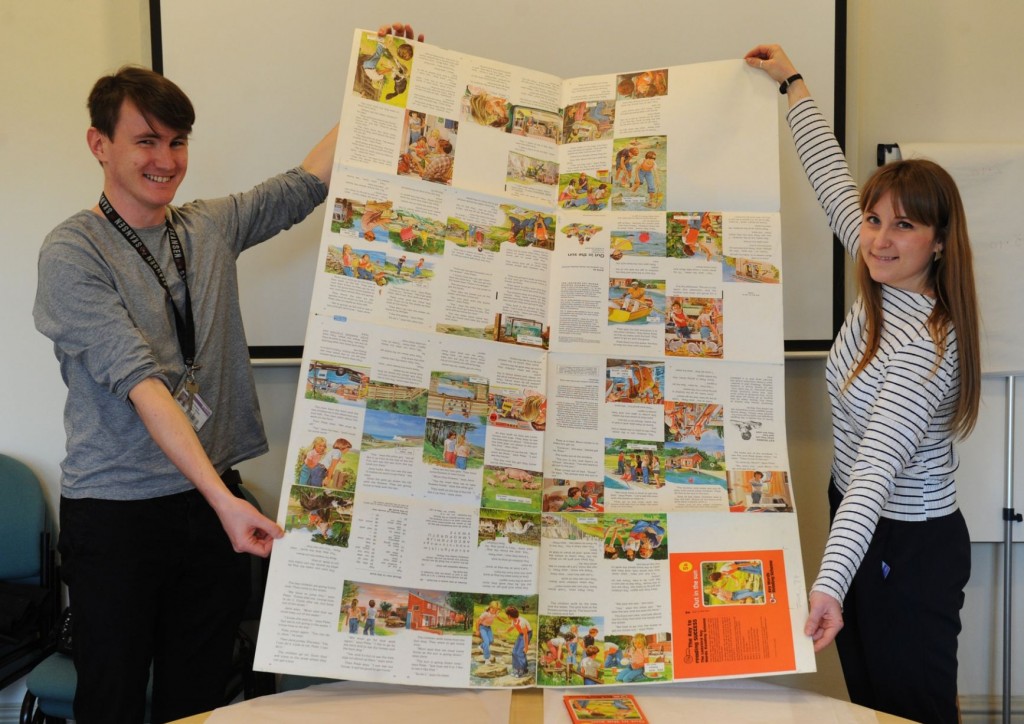

At the moment I’m involved in numerous projects. Aside from the retrospective cataloguing and research project, I’m delivering an events programme called Art Collections in Conversation; I’m working collaboratively to produce a Ladybird Gallery as part of the Museum’s redevelopment, and I’m supporting an exchange programme where the University is hosting a number of artists in residence. In partnership with the Collections Officer I support loans administration and registrar work for the museum. We have an active social media presence so I contribute content for this; I’m also responsible for writing and supporting funding bids, and sorting out tricky things like copyright permissions. I also support the development of 2 young volunteers.

It’s a hugely varied job which I love!

What is your academic background?

Ten years ago I completed a BA (Hons) in Photographic Arts and about 4 years ago I did an MA in Museum Studies.

Whitney: So your course gave you some knowledge for what you are doing now.

Jacqui: Yes, but I don’t think you necessarily need a Master’s degree to work in a Museum. I feel that having a postgraduate qualification in Museum Studies or a cultural heritage subject demonstrates commitment to your future profession, and it taught me a lot about museums. But at the same time there are a number of people that might not have the opportunity to do a Master’s programme. Some people choose internships and vocational placements and enter their museum career completely differently, still achieving the same thing. Now that I’m in this position, I often feel that practical skills can be more valuable.

You studied Photographic Arts as a BA. Has art always been a passion of yours?

Photography has always been something I’ve been interested in. It’s just something I’ve always loved. Once I did my BA I became more aware of the role of the museums and galleries. Material culture, cultural heritage and history are passions.

As an Art Collections Officer are you responsible for collecting Art pieces at all?

We have an acquisitions policy that governs when we acquire an artwork or object. We’re not actively collecting art because we’ve got quite a lot already! It’s about understanding, researching and using the collections that we have. However, there will always be opportunities that arise to purchase something new, or to receive a gift or donation. For example, I was recently involved in acquiring some works for the Museum.

Do you work solely as an Art Collections Officer or do you liaise with other departments and work with other colleagues at MERL?

I get asked to do lots of different things by different people. Rob, the Volunteer Coordinator or Philippa, the Audience Development Manager might approach me and say, “We’re doing this session, what collections do you recommend we use?” or “Can you come in and give a talk?” I am also working with the team at MERL, for example with Caroline the Deputy Archivist and with Ollie the Assistant Curator, to curate a display of artwork within our new Ladybird Gallery. This is part of the wider Our Country Lives redevelopment. Museum work often necessitates collaborative working and relying on curatorial expertise of your colleagues.

Reproduced courtesy of Get Reading

Do you think that has helped you understand the vision of what you need to accomplish and understand the bigger picture?

Yes, there’s definitely a bigger picture. The students are central to my role and giving them greater access to the resources that we have is the bigger picture which trickles down into much smaller ventures, whether it be just giving a seminar or working with Director of Museum Studies, Dr Rhi Smith, on a pop-up display.

How has your experience been at MERL? Is it different to any other institution you have worked in before?

Because of the museum’s extensive and ambitious redevelopment project, it has been an excellent time to join the team. I started at MERL in September 2015. Before that I was at Camberwell College of Arts, and prior to that I was at the Museum of Domestic Design & Architecture. For the past couple of years I have been working with University collections, so I am used to the emphasis on the student, in addition to the traditional museum audience.

What are the rewarding aspects to your job?

I feel privileged to have access to different types of objects, collections and archives and I expect that’s something that all Curators or Collection Managers feel, because that’s probably what gives us our kicks!

How about challenging parts?

When you’re working for a University, the world of academia can sometimes be a little intimidating. You’re often working with a lot of very experienced people. On the plus side, it means you’re working with experts in the field so you’ve got an amazing resource.

How do you think digital technology might change your role or job description in the next coming years?

I think it will definitely change some of the ways that we work and will present new opportunities. The University’s Ure Museum is digitally scanning and printing objects in their collections. Digital platforms present a huge opportunity to engage people with the art collections, at a time when the University doesn’t have a traditional gallery space. It enables us to think imaginatively about how we present the collections online. Digital tools can also aid collections management work, although we don’t currently use them, there are smart phone devices which can assist with tracking object relocations. There are lots of ways that new technologies will change, challenge and enhance the way museums work.

Whitney: So do you think galleries will become much more visual and visible?

Jacqui: Yes. It definitely presents new opportunities. It may mean in the future that you have Curators that specialise in digital technologies and engagement. But you also can’t deny the fact that you are still going to have a physical, historic collection to look after.

Whitney: Is that daunting to think about?

Jacqui: As a bit of a traditionalist and an advocate of analogue technologies and approaches, I find it daunting that in the future a greater emphasis could be placed on the digital rather than the physical.

Whitney and Jacqui continue their fascinating conversation next week!