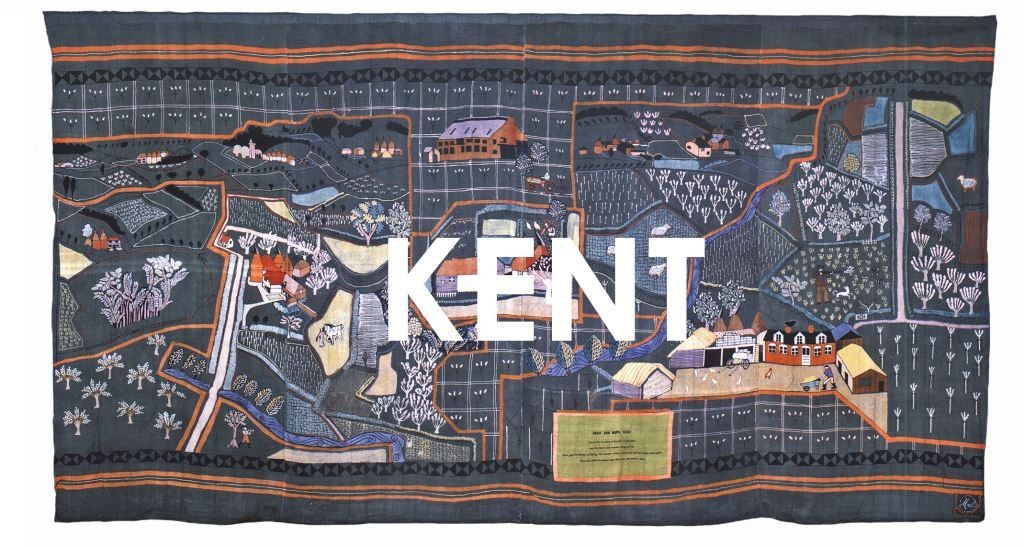

The votes are in, the people have spoken and the wall hanging chosen for display in the new Museum of English Rural Life is…Kent!

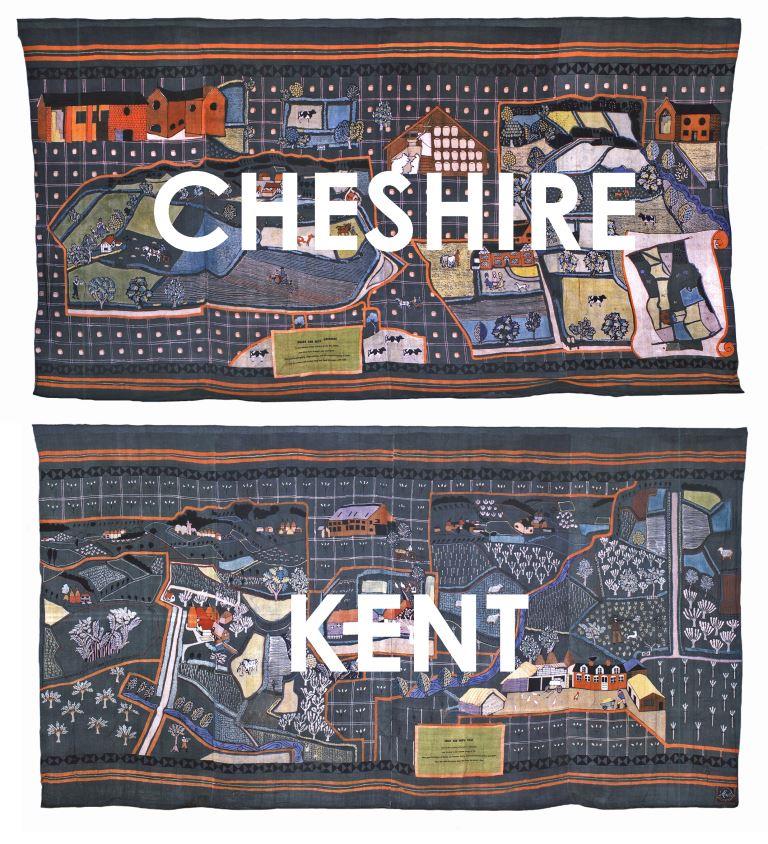

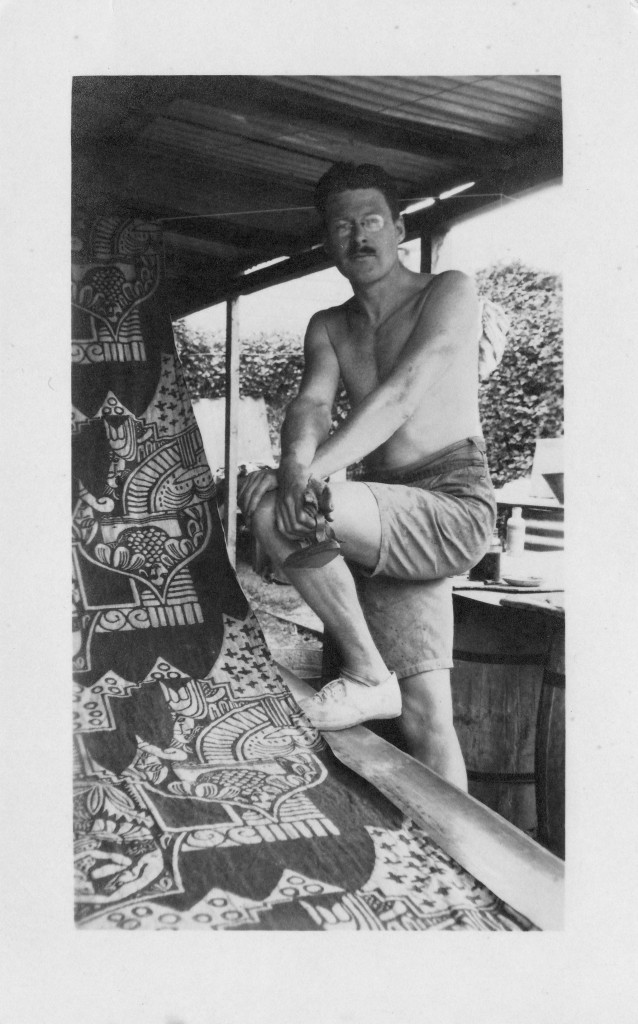

Over the past month we asked you to vote between our Kent and Cheshire wall hangings, two of a series of seven made by the artist Michael O’Connell for the 1951 Festival of Britain.

The campaign culminated in our Museums at Night event, Chalk or Cheese?, where visitors enjoyed each region’s beer and cheese, advocates for both hangings battled it out in a political hustings and everyone had to chance to participate in a secret ballot.

The end-vote was incredibly close; in the end, Kent only won by six votes.

If you’re wondering why the choice is only between two wall hangings, the reasons are actually quite simple (the others depict Rutlandshire, Scotland and Wales, Northern Ireland, Yorkshire and The Fens).

Firstly, we have never had the space or right conditions to display any of these hangings before, so they’ve lain in our Object Store for decades. The cost of conserving each hanging for public display was significant and involved considerable work on the part of qualified conservator Kate Gill. We could not have done this without the funding the Heritage Lottery Fund and the University provided. She removed creases in the fabric, repaired damage, and cleaned and reshaped each of them ready for display.

It’s actually quite lucky that the wall hangings have not been on display in so long, as it means their colours are fresh and vibrant. To keep the colours that way we have to avoid exposing them to too much light, so each wall hanging will only be displayed for five years at a time. One wall hanging will be fully displayed while the other will be rolled and stored at the back of the case, ready to be swapped around in five year’s time.

This of course means that the Cheshire wall hanging will go on display in 2021. We’d love to be able to display them all at the same time, but at a mammoth 7 x 3.5 metres each, we simply cannot afford to case them all (and we don’t have the space!). The case we have bought is bespoke, and has been carefully designed specifically for our wall hangings.

Of course, conservation and environmental factors were less of a concern to our predecessors when they first acquired the hangings back in 1952. They took them immediately to an agricultural show and hung them in the back of a tent in the middle of a field. How times (and costs) have changed!

Thank you to everyone who voted in this campaign, and we look forward to inviting you to see the wall hanging on display this October!