For this month’s Reading Readers blog, PhD student Felicity McWilliams (a familiar face at MERL) gives us an insight into how the MERL collections are playing a part in her research of draught power technology in the 20th century.

An image from Farmers Weekly showing horses and a combine harvester at work together on a farm near Durham in 1961. The farmer also used tractors but on this day they were busy on another task (MERL P FW PH2/C107/76).

Last September, I left my post as Project Officer at the Museum to embark upon an AHRC-funded Collaborative Doctoral Award PhD, based jointly at King’s College London and here at MERL. I’m researching the history of draught power technology on British farms c.1920–1970. Draught power is essentially anything used to pull a load, from carts and wagons to ploughs and harvesters. I’ll admit I often get a blank look back when saying that, though, so I revert to telling people I’m doing a PhD on tractors.

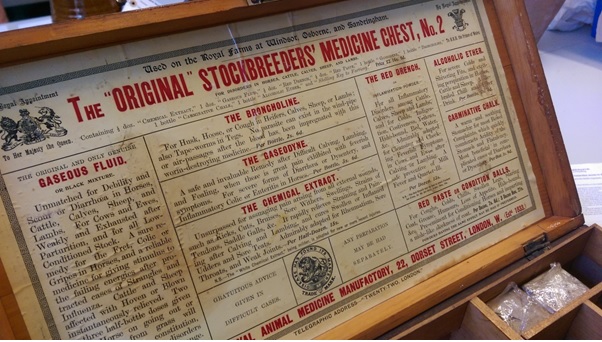

It’s not just tractors though; the technological landscape of twentieth-century British farms included steam engines, horses, oxen, home-made tractors, cars, lorries, jeeps, motorcycles and even military-surplus tanks. Histories of agricultural technology (and of technology in general) have tended to focus on new machinery and innovation. Which is fine, but it means that they look mostly at manufacturers, economics and government policy and rarely at the people actually using the technology – the farmers, horsemen, tractor drivers and farm mechanics. The aim of my project is to research the wide variety of draught power sources that farmers were using and the factors that influenced their decision-making. What they could afford to buy is always important, but I’m also interested to find out how their technological skills, working relationships, values and attitudes might also have had an impact on the animals and/or machines they chose to work with.

Back issues of The Farmers Weekly in the museum’s library.

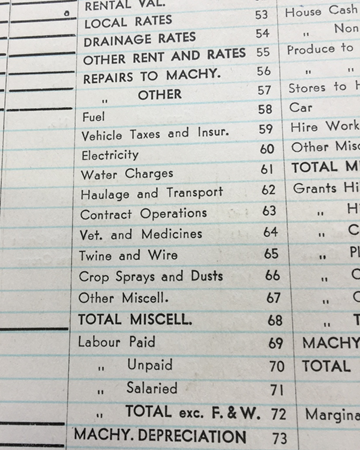

I’ve started by looking at the Second World War period, and over the past few months have spent a lot of time in the MERL archives reading 1940s issues of Farmers Weekly magazine. There are so many features in the magazine which help to show what farmers were thinking, discussing and buying, from adverts and articles to letters and photographs. In fact, there are so many amazing sources in the MERL archives, from films to farm diaries, that it’s a little daunting wondering how I’m ever going to find time to see everything. You can find out more about what’s in the collection here.

We’ll certainly keep up to date with Felicity’s progress and hopefully share some of the interesting things she discovers in her research.