Written by Adam Koszary, Project Officer.

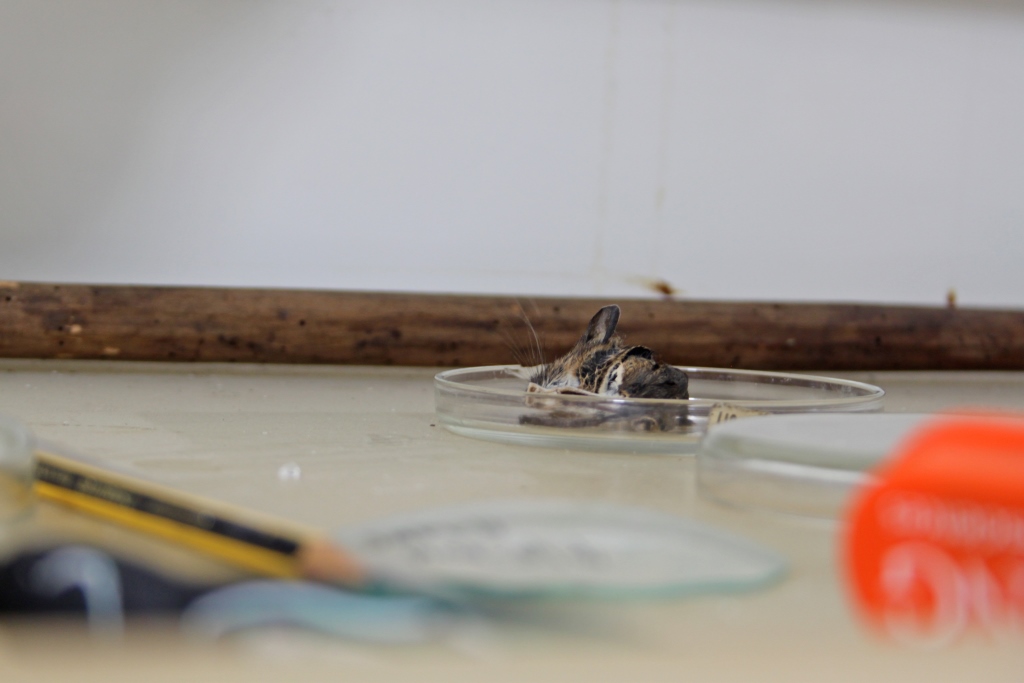

It all started with a story that, five or ten years ago, would have remained within the four walls of the museum and gone no further: our assistant curator found a dead mouse in a Victorian mouse trap.

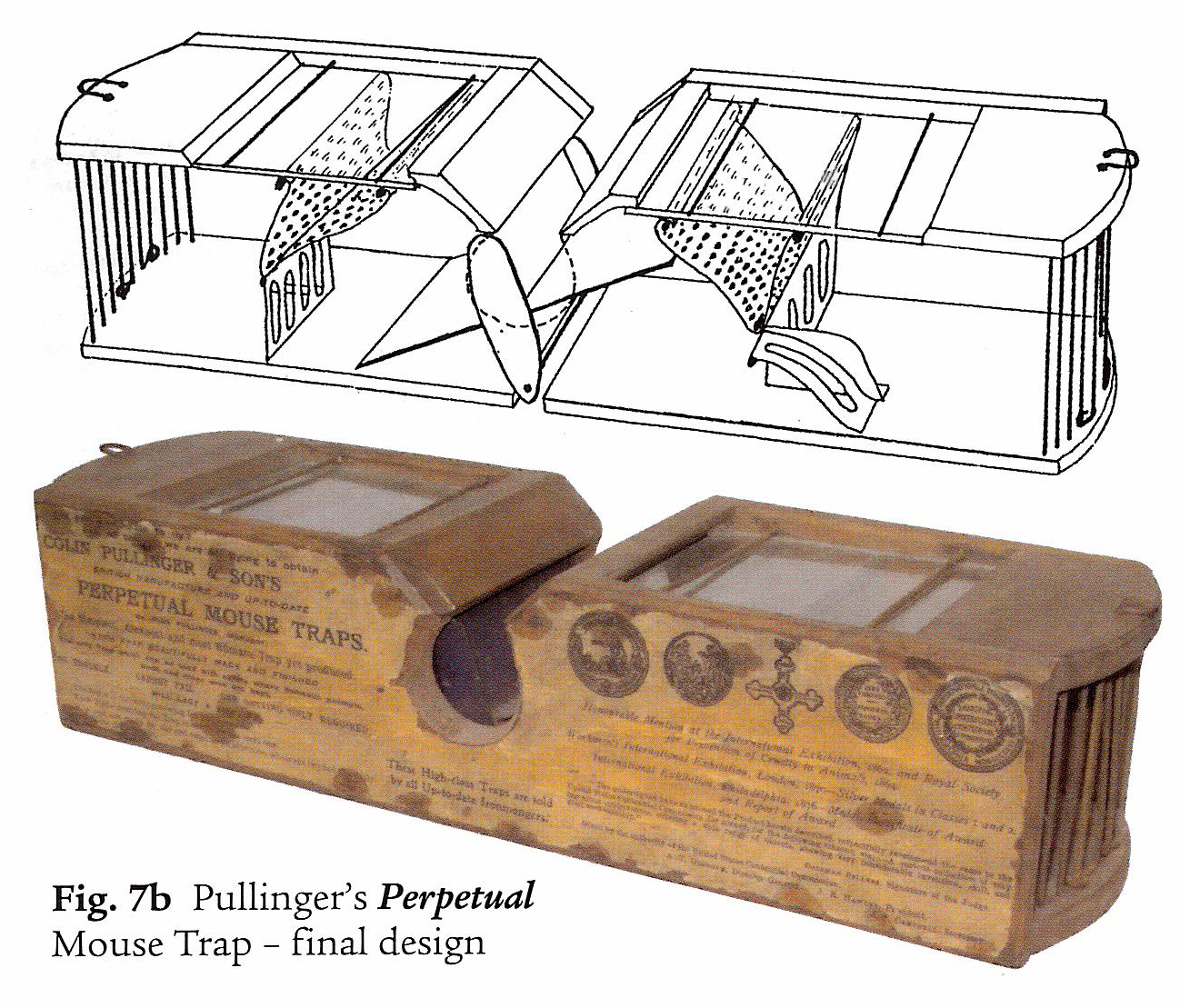

The trap was behind a glass case in our store; it was not baited and it was not on display. And out of the thousands of tasty objects the mouse could have chosen to call both home and dinner, it zoned in on one of the few objects designed to kill it.

As a humane trap, the mouse is meant to be found and then released. Tragically, our mouse would have died a lonely death. Since we check our collection for pests regularly, and don’t expect our traps to be achieving their original purpose, this mouse was simply unlucky to get trapped in a time-frame between check-ups.

We thought the story was interesting and posted about it on our blog and Tumblr. Fast forward five days and it has become global, viral news.

See our other blog post for more information about the trap and an update on what we’re doing with the mouse.

Interest in our Tumblr spiked, and then rapidly returned to normal levels.

And we’re not exaggerating.

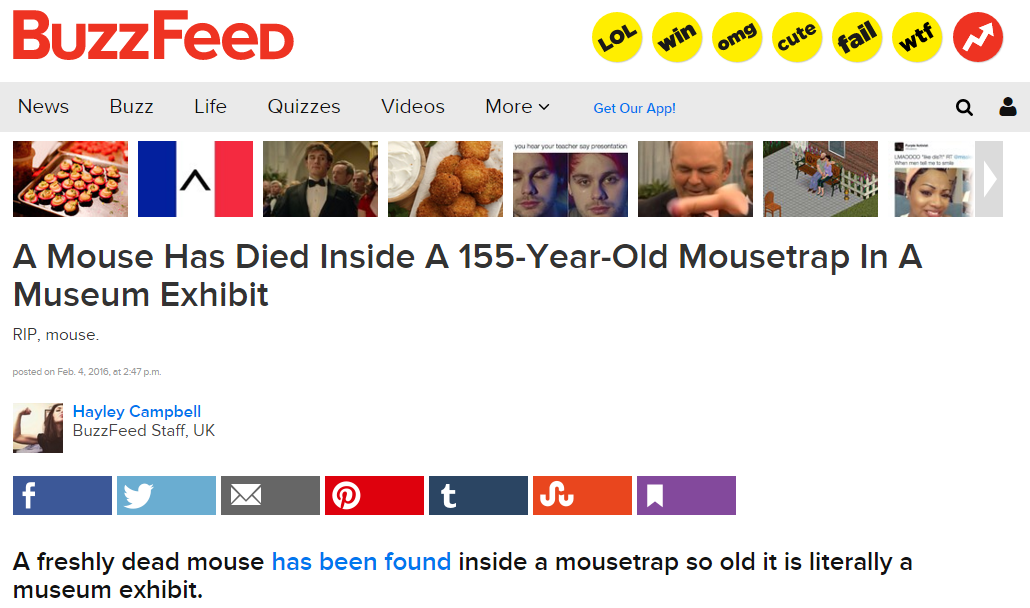

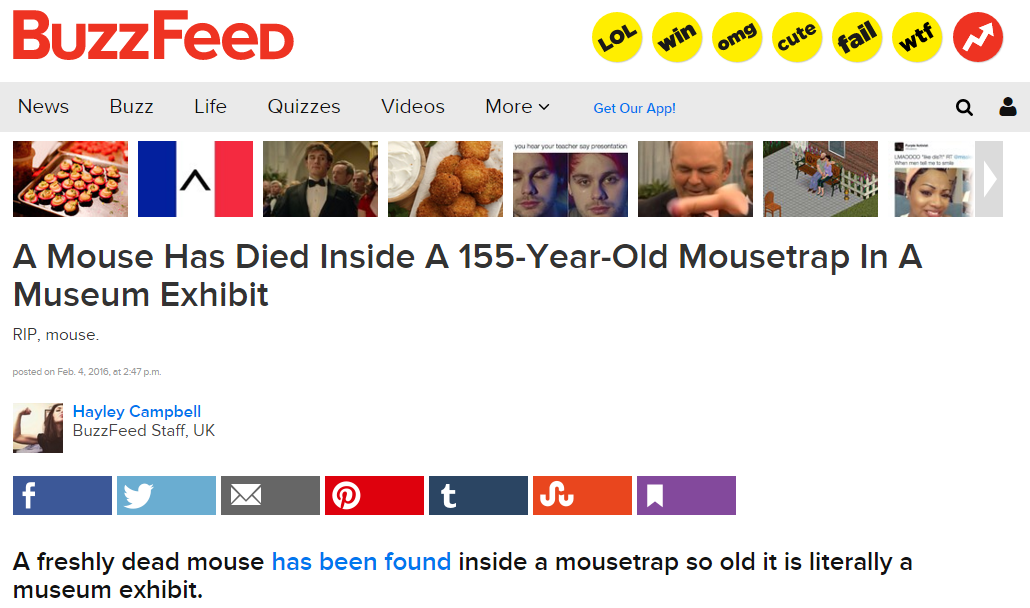

Since the original blog post, we have been interviewed by the BBC and the Canadian public radio broadcaster CBC. After featuring on BuzzFeed the story of our mouse rippled throughout the internet, ending up on The Daily Mail website, ABC, The Huffington Post, I F***ing Love Science and more. We trended on Tumblr, where our post has over 3,000 notes, and have been chosen as a feature of their History Spotlight category. We made the front page of Reddit, and our imgur gallery has been viewed 374,552 times. Our blog has had 67,521 views since the original post, more than the past two years put together.

Not bad for our BuzzFeed debut.

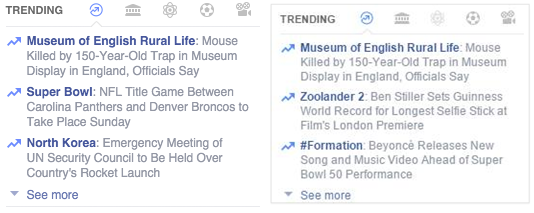

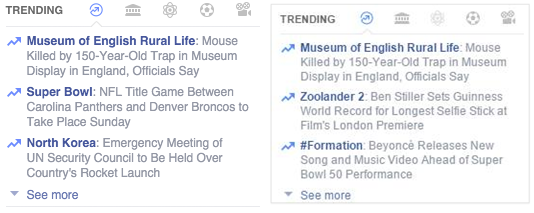

We thought everything had died down by Sunday, but then news started trickling in that we were trending on Facebook across the world. And not only that, but that we were trending higher than the SuperBowl, North Korea and…Beyonce:

Suffice to say, we’ve never had it so good on Facebook.

So what was the viral timeline of events? It all started with our original blog post, which was also cross-posted to Tumblr, and from there:

- We were messaged by a writer for Atlas Obscura on Tumblr asking permission to use our photographs. While we debated how to respond, the article was posted anyway. Our Assistant Curator was wrongly identified as a woman, but this was soon corrected

- Nick Booth, of UCL Museums, put a Buzzfeed writer in touch with the author of the original blog, Adam Koszary

- The Buzzfeed article was published, and then other websites rapidly picked up on the story, put their own spin on it and re-posted it on their own sites

- With a nudge, we were retweeted by Neil Gaiman but, more importantly, reblogged on Tumblr by him as well. Our original Tumblr blog jumped from c.200 notes to around 1800 in the space of a few hours

- Coverage continued, with our submitted story making the front page of Reddit and being featured on Saturday morning BBC Breakfast

- As more and more websites picked up the story we were also featured on various Facebook pages. As pages such as I F***ing Love Science shared the story, the MERL Mouse was suddenly trending across the world.

Our mouse made the ‘front page of the internet’, better known as Reddit.

Needless to say, there does not seem to be one recipe for going viral. What seems essential, however, is recognising when you have a good story, writing it well and having nice pictures.

From there it took getting our story in front of the right person – in this case Buzzfeed’s Hayley Campbell – and then watching the dominoes of ‘clickbait’ websites fall. We also nudged the story along, soliciting a retweet from a ‘power user’ of Twitter and Tumblr, Neil Gaiman, as well as posting updates and providing different angles on the story, such as our image gallery on Reddit.

We were lucky that we had been building our expertise and capacity in social media for some years, meaning we could hit the ground running when it became obvious the story was a hit. Our online network of museum professionals and journalists was essential to its success; without Nick Booth alerting Hayley Campbell to the story, it may not have kicked off in the first place.

However, before we publish blogs from now on, we’ll definitely be asking ourselves: ‘Would we be happy if this went viral?’ In hindsight, we were glad to have explained the ethical and practical issues involved with having a dead mouse in a museum object, as well as why and how it may have happened. Trust is very important to a museum, and if this story had gone viral without us considering the deeper issues we may have suffered immense damage to our reputation. There are many other stories about the important work we do as a Museum which we’d preferred to have gone viral, but nevertheless we hope those who saw the story have learnt a bit more about conservation, the continuing relevance of museum objects and how even the smallest of tragedies can captivate the world.

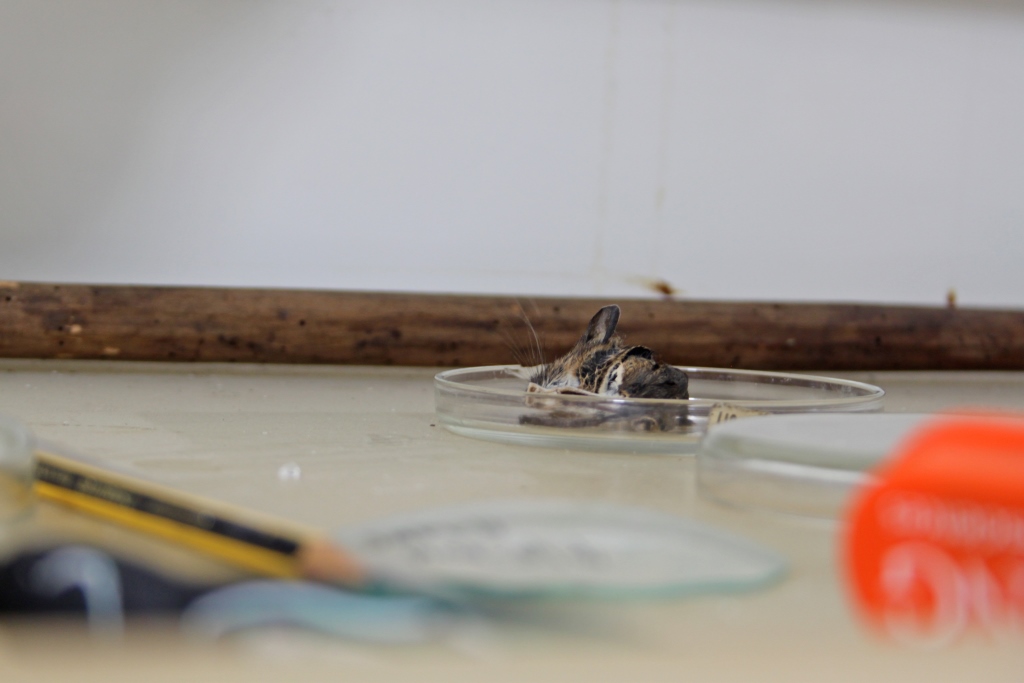

The mouse is currently being prepared by our Conservator.