Science engagement volunteer, Eilish Menzies, considers beekeeping and the role that it plays in food production.

Walking through the MERL galleries you can see the crucial role bees play in past and present global food security. By simply taking a stroll through the collection, you can really get a sense of the progressive steps that honey production has made and inspired throughout agriculture. Our library, archives and Special Collections also contain multiple historical books on bee keeping, bee anatomy and honey cookbooks. However, for a process so old and ingrained in societies all over the world, it seems strange that we are now facing an international reduction in bee colonies.

Much like humans, bees are social creatures, meaning they live together in large colonies. They present one of the few examples of true eusociality, where all individuals in the hive work by cooperative division of labour. The hive is essentially controlled by one female, known as the queen, whose sole function is to reproduce. As the name would suggest, honey bees produce honey. This is their primary source of food and it is obtained from the nectar of plants.

Bees on the whole are incredibly important players in the ecosystem ballgame. When foraging for food they act as pollinators for a range of different plant and tree species, and contribute £200 million to crop production every year in the UK. It’s estimated that one in every three mouthful of food we eat is dependent on pollination by bees.

Illustration from Life of the Honey Bee.

© Ladybird Books Ltd www.vintageladybird.com

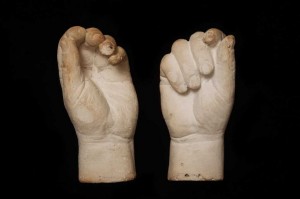

Our relationship with bees stems back millions of years, when ancient human cultures would collect honey from wild bee colonies. However, this wasn’t for the faint hearted, as it almost always involved climbing to high and hard to reach places and sticking your hand in a nest of unwelcoming bees. It wasn’t long until humans began to domesticate bees by providing artificial spaces to house the hive. As the growth of bee keeping continued to spread, many new structures were produced to improve the collection of honey. The typical hives you see today are known as Langstroth Hives, named after Lorenzo Langstroth. His design has remained relatively unchanged for over 160 years.

A Langstroth Hive from our A Year on the Farm gallery.

As for the future of bee keeping, things seem a little bit uncertain. National statistics show that bee populations have not been able to keep up with the increased demand for honey. Disease and harsh winters have meant the global production of honey has become much more irregular, leading to an increase in price. As pollinators, bees are responsible for large proportions of global agriculture, meaning a decrease in their population could have severe consequences on food production and ultimately our survival. This issue becomes apparent when you consider the role of bees within the pollination of rural crops around the globe. Smallholder agriculture makes up 80% of the crops in Africa and Asia and is particularly important in developing communities. For the 2.5 billion people living off of these crops, optimising pollination could be the primary approach in food security schemes.

As the MERL galleries demonstrate, change and uncertainty has always plagued our agricultural industry. We can only hope that the bee populations and the honey industry continue to adapt to these changes and that our future collections will be filled with the results of these achievements.

Save