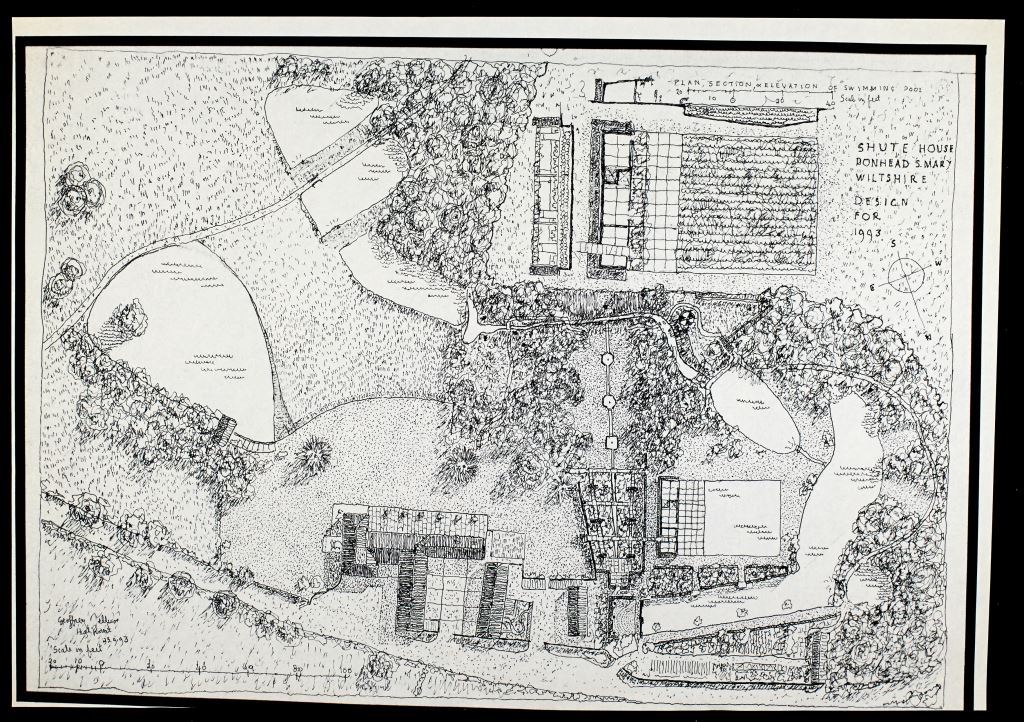

This year, thanks to generous funding from the Landscape Institute, we are pleased to offer bursaries to encourage use and engagement with our varied and fascinating landscape collections. Read more about our Landscape Institute collection here, including the collections of Geoffrey Jellicoe, Sylvia Crowe and Brenda Colvin. See a full list of our collections here.

Details below, please apply by email to merl@reading.ac.uk

![From AR COL A/6/5, Folder relating to Little Peacocks Garden, Filkins [Brenda Colvin's home from 1960s]](https://blogs.reading.ac.uk/merl/files/2015/02/AR-COL-A_6_5-Little-Peacocks_8.jpg)

From AR COL A/6/5, Folder relating to Little Peacocks Garden, Filkins [Brenda Colvin’s home from 1960s]

Student travel bursaries

The purpose of the student travel bursaries is to enable students to access collections held at Reading related to landscape, including landscape design, management and architecture.

We are offering 2 bursaries of £150 each.

Applications will be by email to merl@reading.ac.uk (please put “Landscape Bursary” in the subject line) will be invited from any student in part or full-time higher education.

Interested applicants should submit a CV, and a short statement (max 400 words) outlining their interest in and current work on landscape, stating how the bursary would be spent and how it would be beneficial to their studies. Applicants should identify those materials in the archive that would be of most benefit to them.

Plate from ‘The art and practice of landscape gardening’, by Henry Ernest Milner, MERL LIBRARY RESERVE FOLIO–4756-MIL

Academic engagement bursary

The purpose of this award is to encourage academic engagement with collections held at Reading related to landscape, including landscape design, management and architecture.

Successful proposals will attract a stipend of £1,000. The funding can be used to offset teaching and administration costs, travel and other research-related expenses. Appropriate facilities are provided and the successful applicant will be encouraged to participate in the academic programmes of the Museum.

The intention for this award is to create an opportunity for a researcher to develop and disseminate new work in the broad arena of landscape.

Applications will be by email to merl@reading.ac.uk (please put “Landscape Bursary” in the subject line). Interested applicants should submit a CV and a statement (max 800 words) outlining their interest in, and current work on, landscape.

Timetable

Academic engagement bursary:

1 September 2016 – applications open

31 October 2016 – applications close

30 November 2016 – successful candidates announced

Any work will need to be carried out and monies claimed by 31 July 2017.

Student travel bursaries:

1 September 2016 – applications open

28 February 2017 – applications close

31 March 2017 – successful candidates announced

Any work will need to be carried out and monies claimed by 31 July 2017.

For informal enquiries please email c.l.wooldridge@reading.ac.uk

We look forward to receiving your applications!