written by Adam Koszary, Project Officer.

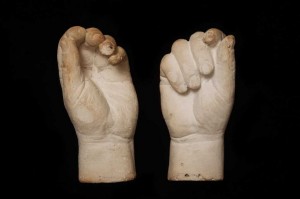

One of the biggest complaints levelled at museums is that visitors cannot touch anything. Objects are put tantalisingly out of reach behind thin Perspex and glass, or an arms-length behind a velvet rope. It is annoying because objects are almost always meant to be touched, and especially so in our museum where many of our objects are made by hand or made to be used by hands. We have tools which benefit from decades or centuries of refinement to fit perfectly in the hand, as well as textiles, ceramics, pulleys and cranks which demand to be touched – their roughness, smoothness, ridges, pits, dimples or simply put: their texture, is often integral to understanding them. However this then runs up against the fact that if we let visitors touch everything, we soon wouldn’t have a museum left. We often ask our visitors not to touch because we have to ensure that the collection remains whole and in good condition for future generations to enjoy.

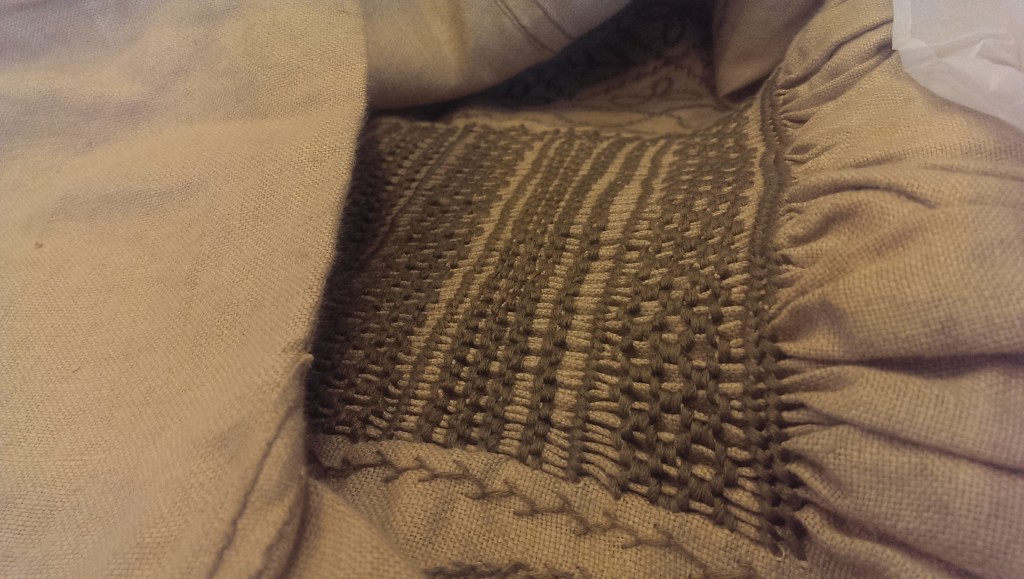

We spent a morning and part of the afternoon yesterday exploring this tension between preservation of our objects and all of the reasons why objects should be touched. It is obvious how simply by touching and interacting with an object you can learn so much more from it. By exploring a smock close-up you can see and feel the irregular hand-sewed seams as well as more fully appreciate the intricate detail of the smocking; by holding a flail you can feel how surprisingly light it is, yet imagine how heavy it may be after a day’s work (and the smoothness and many repairs of the flail showed it definitely had seen many a day’s work). There is also the fact that some people learn more from hands-on activities, and for people with visual impairments it is a necessity.

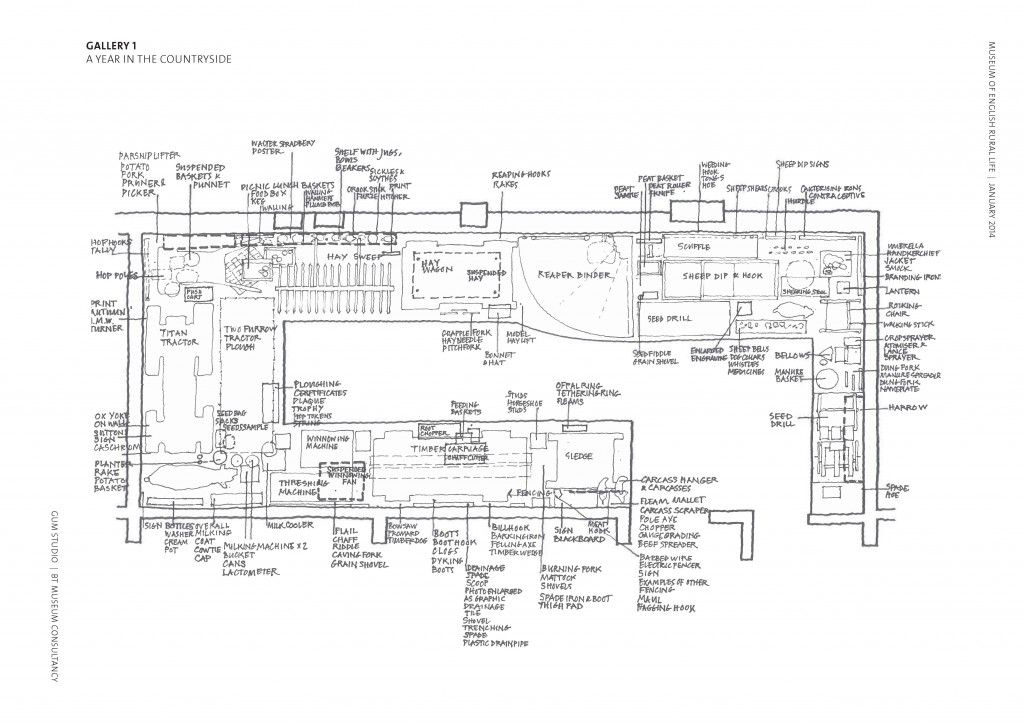

It is fair to say, then, that people both specifically and in general can only learn so much by reading a label and looking at an object, and as such we are exploring the different ways in which we could have objects available to handle by group-booked sessions and normal gallery visitors. After looking at case-studies from the Manchester Museum, the Horniman Museum and the Museum of London, we began to look into the idea of volunteer-led handling opportunities within the galleries, as well as the logistics of creating a handling collection. Of course, we already do have some handling of objects at some events and visits, but it has usually been on an ad-hoc basis. However, the new galleries of MERL as part of Our Country Lives also mean we have a great opportunity to integrate handling into everything we do, and make it a permanent feature of the new museum. Our next step is to ensure we are targeting the right audiences with our handling opportunities, and decide what themes the handling collection should cover. We’ll be working with Charlotte Dew on how to plan and implement a new handling collection, who is helping us as part of our Arts Council England-funded project Reading Engaged.