Reading has a long and proud history of teacher education and its roots can be traced to the creation of the University Extension College in 1892. At first, courses took place in the ‘Pupil Teachers’ Department‘, but in 1893 it became known as ‘The Normal Department‘ and the name remained until 1897.

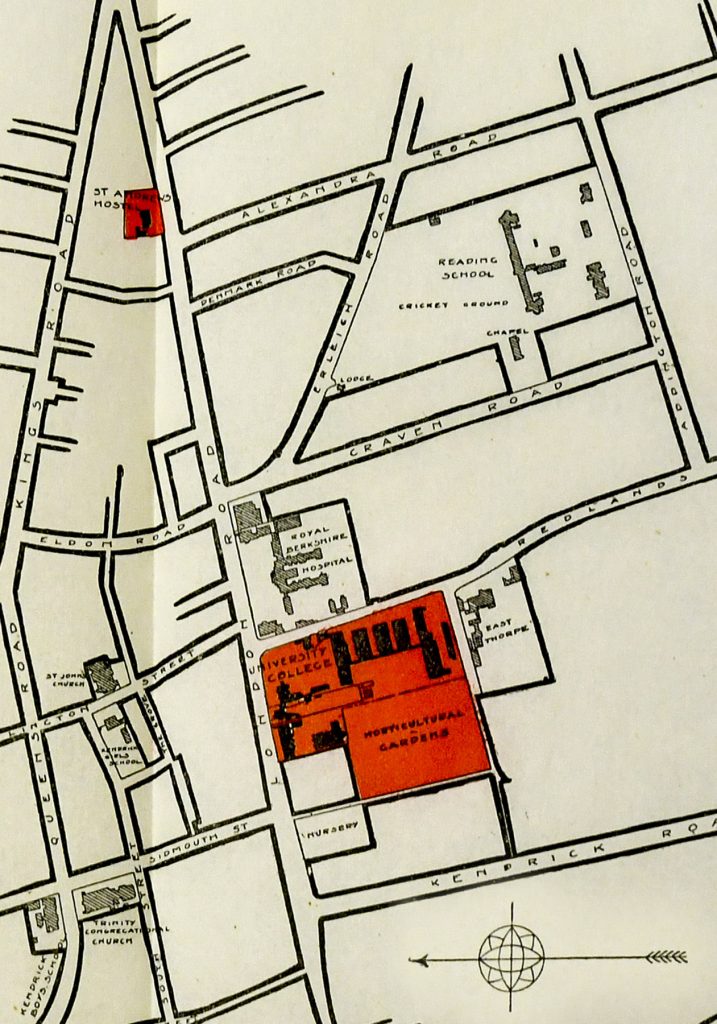

The map below, published in the Calendar of 1893-4, shows the location of the Normal Department on the site of the Extension College in Valpy Street. Only a year previously the department’s premises had been the vicarage of St Lawrence’s Church.

Until 1899 when it became a Day Training College, the work of the Department was fairly limited in scope and focused on subject knowledge rather than pedagogy. In the first year of the Normal Department it covered three main areas:

-

- Pupil Teachers attended classes on Saturday mornings and on weekday evenings after school. They were entitled to an allowance of 3 hours per week private study at school. Fees of £2 per annum were paid by their schools.

- Uncertificated Assistant Teachers attended courses of instruction that included Algebra, Geometry, Arithmetic, English, Music, Geography and History. There were separate timetables for men and women: men were not offered Music and women were offered fewer subjects because they had no access to Algebra or Geometry. The timetables make no mention of science. Participants paid somewhere between 4 shillings and 6 pence and 10 shillings and 6 pence per term, depending on its length and whether or not students attended small-class tutorials.

- The College collaborated with Berkshire County Council to provide classes for teachers in rural Elementary Schools. Courses gave technical instruction in areas such as Agriculture and Hygiene over a period of three years. They were held at Didcot, Newbury and Reading.

The duties of the Normal Department were carried out by a staff of six, led by a Superintendant and assisted by a Senior Tutor. They are named in the extract from the Calendar of 1893-4 shown below and include W. M. Childs who was later to become the University of Reading’s first Vice-Chancellor.

In his memoir ‘Making a University‘, Childs gives an interesting insight into the business of educating pupil teachers:

‘As for the pupil teachers, they almost defeated me … I had been told that until lately all these pupil teachers had been taught on traditional lines by their own head teachers in their own schools, and that herding them into central classes was not popular.’ (p. 3)

The students were prepared for the Queen’s Scholarship Examination by which the thousands of entrants were rank-ordered in order to determine admission to training colleges.

Childs was not impressed, expressing sentiments that would strike a chord in some quarters today:

‘Under this forced draught, competition became nerve-racking, and mental preparation a hot-bed of cram. All teaching was ‘suspect’ unless it ‘paid’ ; and no device of memorizing was deemed too sordid if only it would win marks.’ (pp. 3-4)

Nevertheless, Childs overcame his difficulties with the ‘genial disorder of the handful of boys‘ and the whispers of the girls. And he claimed that all his teaching skill derived from these early years of struggling to manage pupil teachers’ attention and goodwill.

What was ‘Normal’ about the department?

I had never encountered the use of ‘normal’ in the context of UK teacher education before. I was, however, acquainted with the ‘écoles normales‘ in the French system. Professor Cathy Tissot, then Head of the Institute of Education, told me that both ‘Normal Department’ and ‘Normal School’ had been standard terminology, historically used, in the United States.

A survey of Google Books showed that during the 19th Century and the early decades of the 20th, collocations of both normal+department and normal+school were many times more frequent in US publications than in the UK and that US usage fell towards UK levels after 1940. Later usages tend to be historical accounts of educational settings.

The Oxford English Dictionary records eight citations of this sense of ‘normal’ but they didn’t explain what was ‘normal’ about a Normal Department. So I sent a query to ‘Grammarphobia’, a blog based in the USA about usage, word origins and grammar run by Patricia T. O’Conner and Stewart Kellerman. They pointed out that the term originally had to do with norms and standards and that the schools, departments, colleges and universities were normal in the sense of providing a model. Their carefully researched reply that encompasses usage in France, Britain and the US can be read in full here.

A future post will look at the next significant stage in the development of Teacher Education at Reading that laid the foundations for what was eventually to become today’s Institute of Education. This was the creation of the Day Training College in 1899.

Thanks

To Prof Cathy Tissot for originally raising this topic.

To Patricia T. O’Conner and Stewart Kellerman for their excellent blog and their speedy response to my queries.

Sources

Childs, W. M. (1933). Making a university: an account of the university movement at Reading. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd.

Reading College. Calendar, 1898-99.

University Extension College. Calendar and general directory of the University Extension College, 1892-3.

University Extension College. Reading. Calendar, 1893-4 to 1897-98.