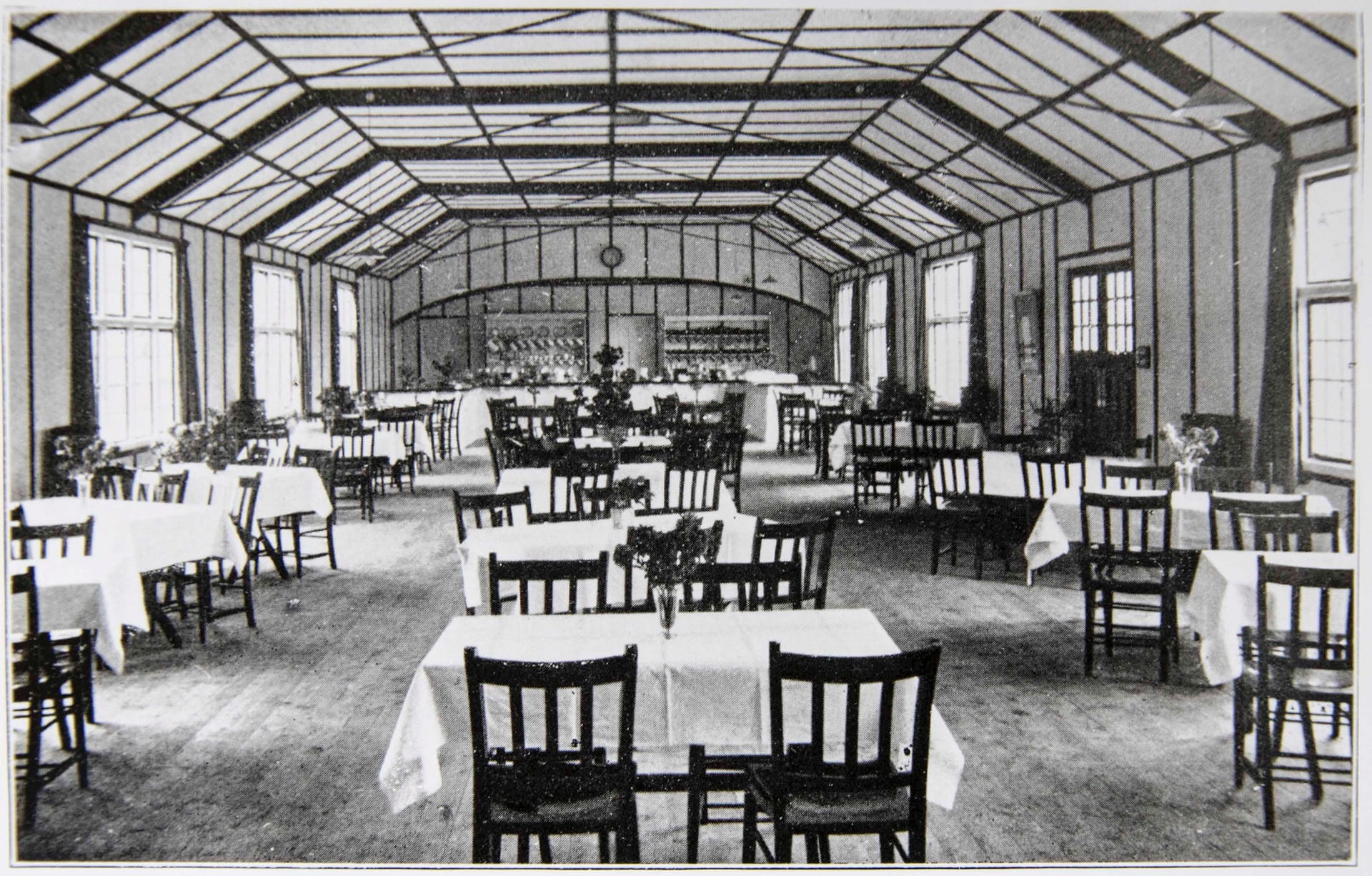

On the 7th July 1977, the University of Reading hosted the William Smith’s Children’s Book Fair. The venue was the Great Hall on the London Road Campus.

Details of this can be found in the archive of Christine Pullein-Thompson in the University’s Special Collections. Christine, together with her twin sister Diane and older sister Josephine was a children’s author, renowned for her popular pony stories. The Pullein-Thompson sisters were local to the area, having grown up in the village of Peppard in Oxfordshire where they lived in a house with its own stables. They were riding horses and writing stories about them from an early age.

Christine lived from 1925 to 2005 and was the most prolific of the three sisters, producing over 100 books with translations into 12 languages.

The Book Fair

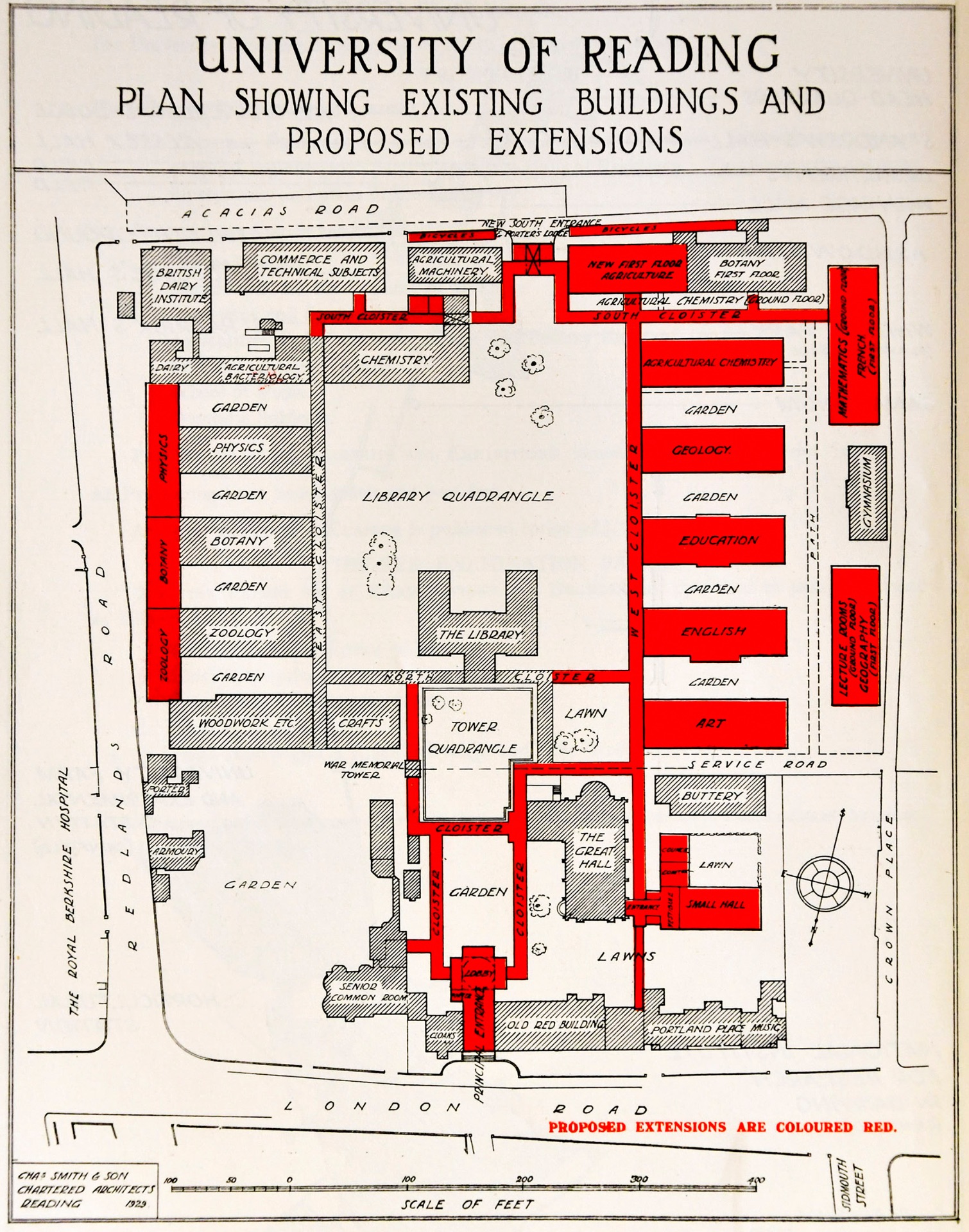

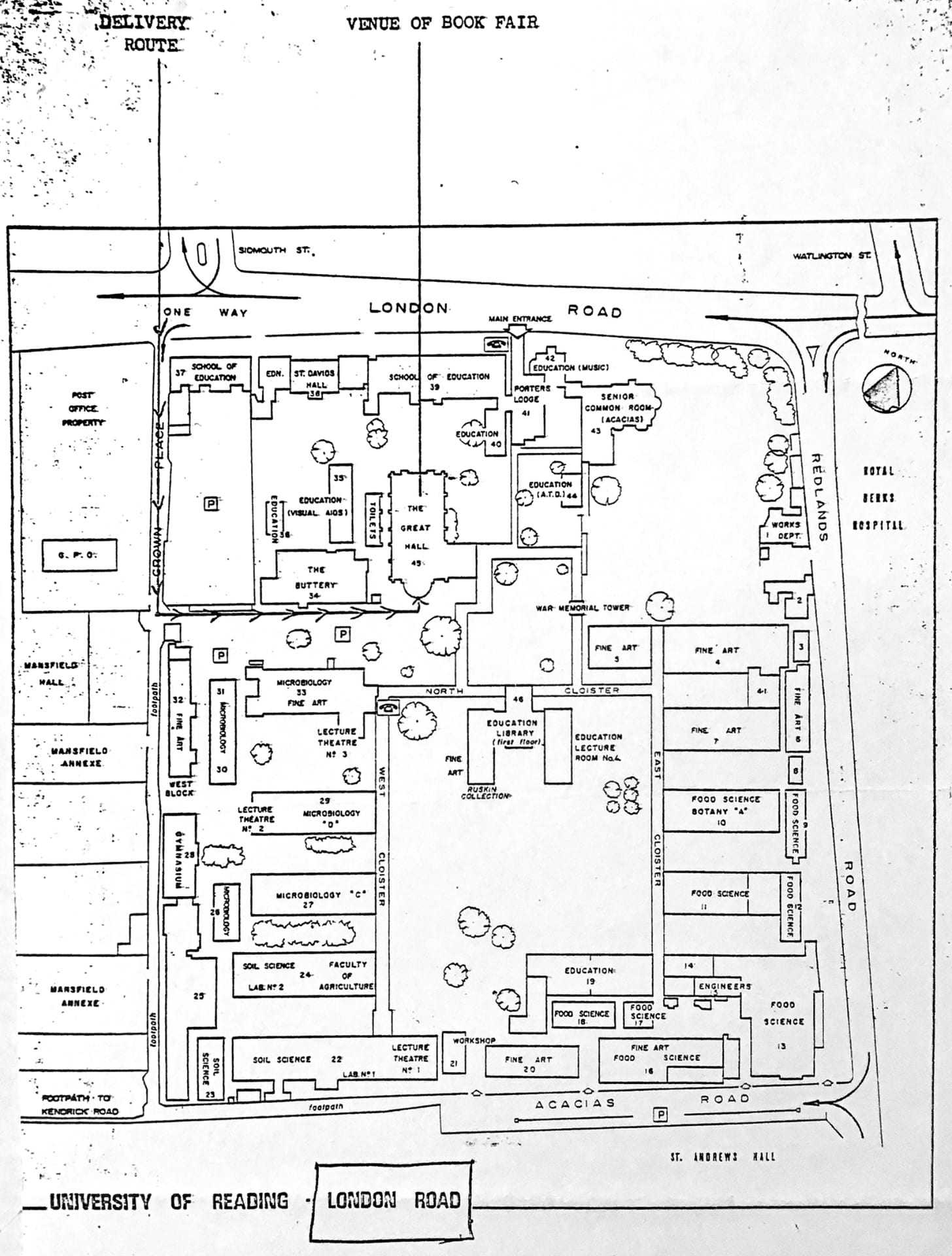

On 12th May 1977 Granada Publishing Ltd., Christine’s publisher, wrote to her address in Middle Assendon, Henley. They had arranged for her to attend the Children’s Book Fair in Reading in July, and enclosed maps of the location of the University and the position of the Great Hall at London Road.

She was to conduct a ‘guess the weight of the pony articles’ competition, with Granada supplying 50 of her books as prizes. There would also be ‘further stock available for direct sale.’

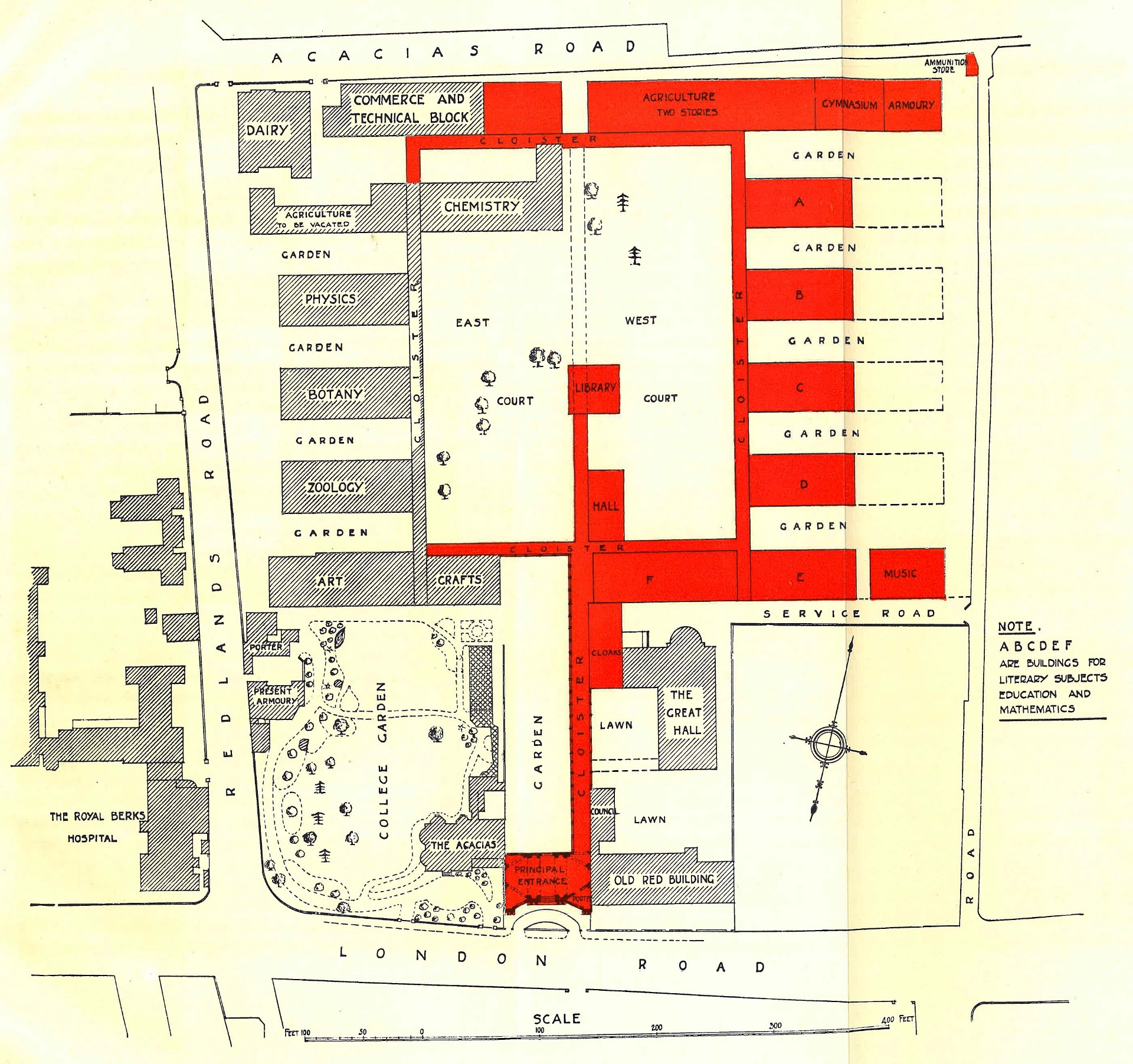

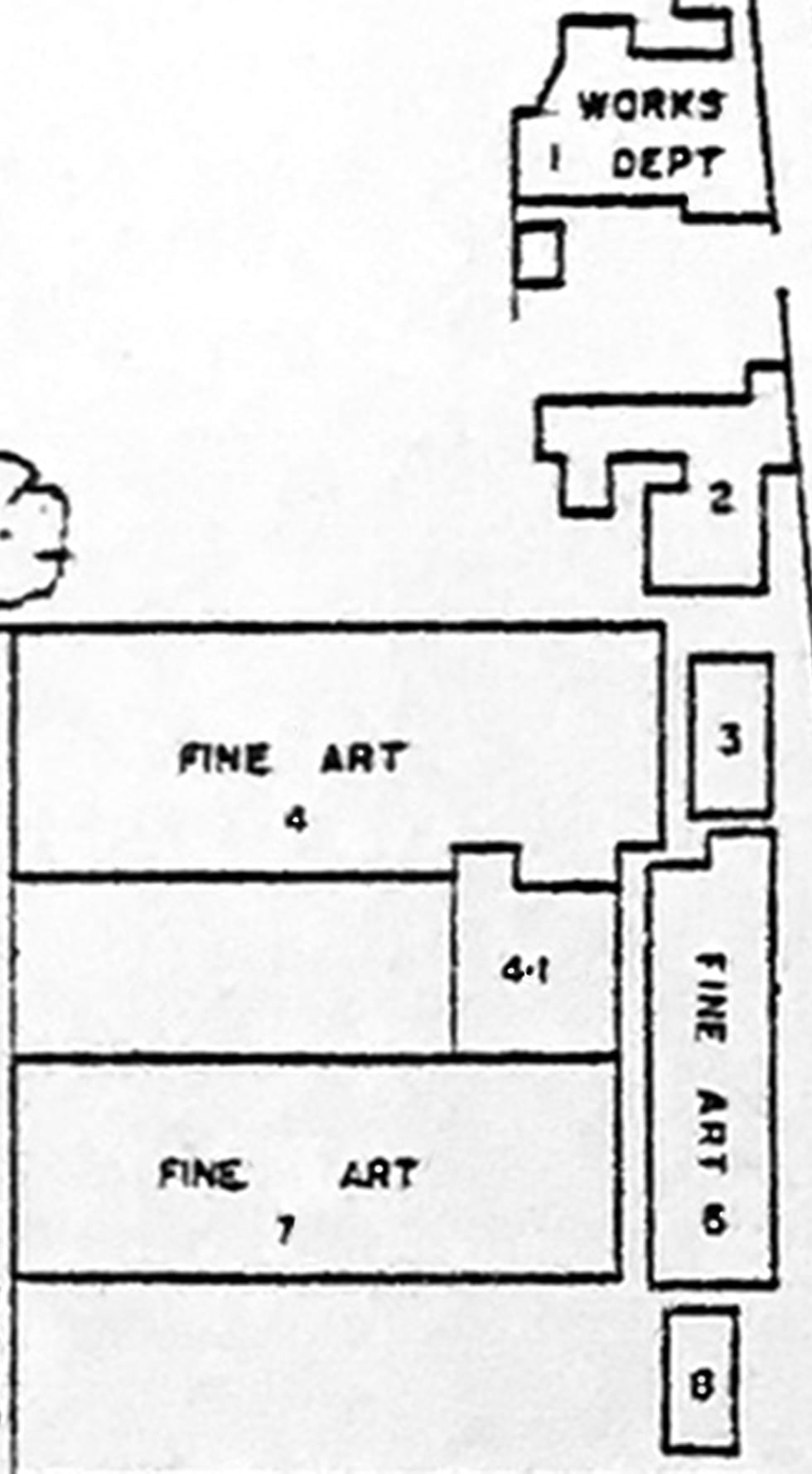

The Map of the Campus

The plan of the London Road Campus in 1977 was new to me. I find it interesting because it is a previously missing link between the pre-Whiteknights maps of the 1930s and ’40s and my own memories of the site from when I joined the School of Education in 1987.

This is also the first map I have seen that includes numbered buildings. And most of them bear the same numbers as today (L16, L19, L22, L33, etc.). This original numerical system counted in a roughly clockwise direction beginning with the Works Department in the top right hand corner and ending with Acacias (L43, the Senior/Staff Common Room), and L44, commonly known as ‘The Dolls’ House’.

If this numbering system seems less obvious now it is because many buildings no longer exist or are no longer occupied by the University – the Buttery (Building 34 between the Great Hall and L33) burnt down in 1982 and along London Road, the Old Red Building and Portland place have become private accommodation.

Some other adjustments had to be made too. For example, Fine Art Buildings 4.1, 6 and 7 are now, in 2024, occupied by Art Education and bear the single designation, L4.

In earlier maps of the 1930s and 40s, Buildings 4 and 7 had been separated by a garden and labelled Fine Art and Zoology respectively; building 4.1 that linked them had yet to be constructed. Buildings 3, 5 and 8 on the map have all disappeared.

Other notable absences from today’s campus that must be especially salient for members of the Institute of Education are the two Food Science buildings between L16 and L19, and the Fine Art block between L16 and L22. The full extent of demolitions can be seen below.

Consequences of the move to Whiteknights

The purchase of Whiteknights Park by the University had been completed in 1947. Building on the site began in 1954 and in 1957 Queen Elizabeth II performed the official opening of the Faculty of Letters, now the Edith Morley Building.

The effect of the gradual migration of departments from London Road to the new campus can be visualised in the version below of the 1977 map. The site was now dominated by five departments: The School of Education, Fine Art, Food Science, Microbiology and Soil Science.

The School of Education had been founded in 1969 through the amalgamation of the regional Institute of Education, established in 1948, and the University’s Department of Education. It is possible that at least one of the buildings labelled Fine Art was, in fact, devoted to Art Education. This was certainly the case in 1987 when part of the ground floor of L16 was occupied by Fraser Smith and his fellow Art Education colleagues James Hall and Richard Hickman.

Sources

Gillet, C. R. E. (1949). Reading Institute of Education. In H. C. Barnard (Ed.), The Education Department through fifty years (pp. 45-47). University of Reading.

Holt, J. C. (1977). The University of Reading: the first fifty years. Reading: University of Reading Press.

University of Reading Special Collections. Christine Pullein-Thompson Collection, Correspondence with Publishers, Granada: MS 5078/107.