The education and training of Pupil Teachers formed a significant proportion of the work of the University Extension College (1892-8) and Reading College (1898-1902). In a post about Reading’s ‘Normal Department’ I included information about Pupil Teachers and their attendance. On his appointment to the College in 1893, it was the job of W. M. Childs to teach them English history, something that all but defeated him:

‘…. at first it was uphill work, and sometimes I returned to London more that half inclined to throw up my job.’ (Childs, 1933, p. 4).

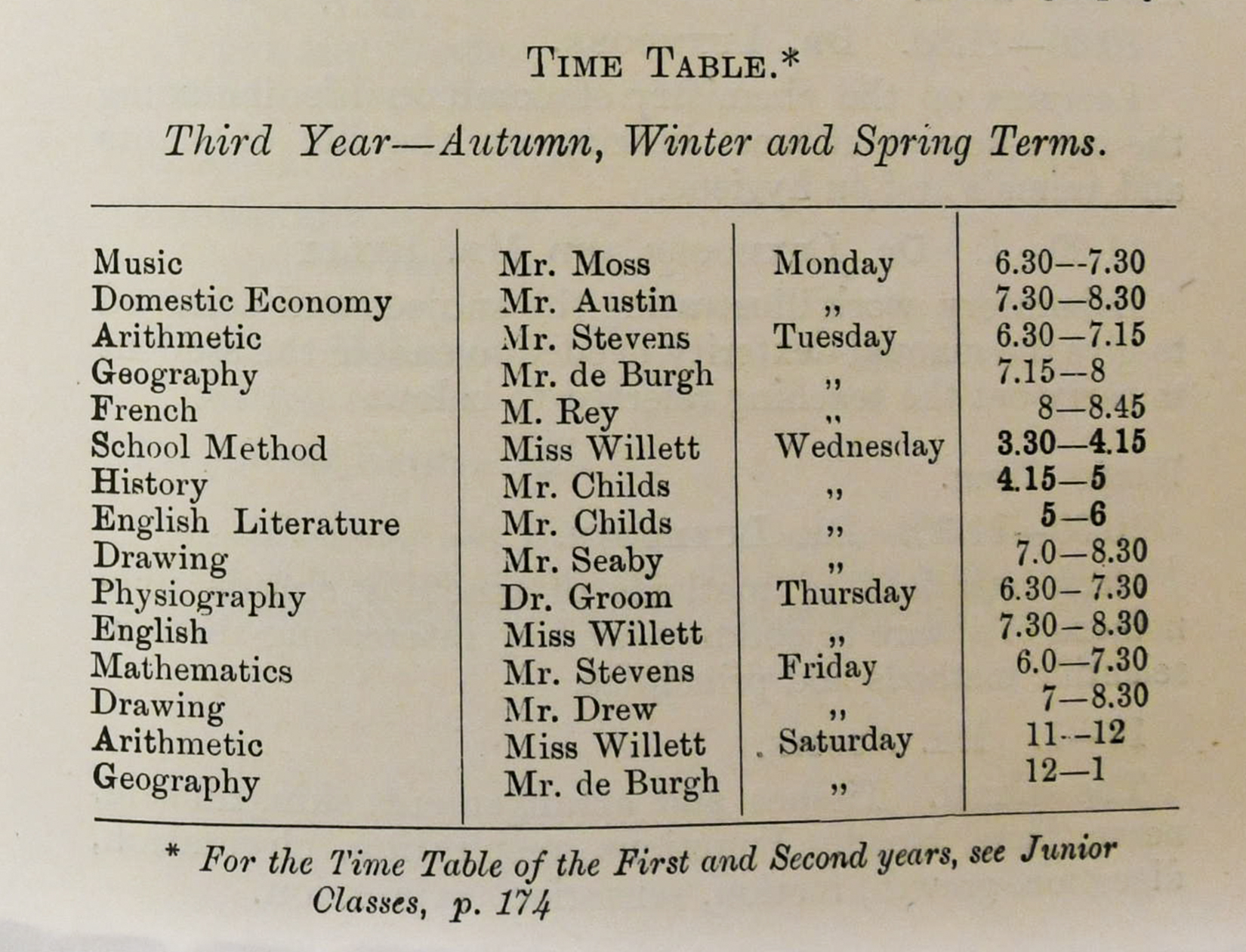

Below is the timetable for the third-years during 1899-1900. Four of the staff (de Burgh, Rey, Childs and Seaby) are in the photo of the Education Department at the end of the post, Teacher Education, Albert Wolters and the ‘Criticism Lesson’ :

Textbooks are specified in the College Calendar for History, Geography, English Language and Literature, Music, Algebra, Euclid and Mensuration.

The courses were intense and sometimes highly academic. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the choice of textbooks for English Grammar. Until 1898 two books were listed:

-

- Outline of English Grammar, by C. P. Mason (Bell and Sons), 2s.

- For Fourth Year. Historical English Grammar, by C. P. Mason (Bell and Sons), 3s 6d.

I have never seen copies of either of these, but in 1899 they were replaced by a single volume:

-

- English Grammar, past and present, J. C. Nesfield (Macmillan), 4s. 6d.

No doubt the students were thrilled to be saving a whole shilling on the deal; whether they were thrilled by the grammar is another matter!

Nesfield’s grammar was first published in 1898 and my own copy, bought in a second-hand bookshop 40 years ago, is the reprint of 1900:

The work is divided into three main sections followed by appendices:

-

- Modern English Grammar

- Idiom and Construction

- Historical English: Word-Building and Derivation

- Appendices on Prosody, Synonyms, and other Outlying Subjects.

The 470 pages of small print must have been a formidable challenge for the Pupil Teachers.

Some of the terminology in the volume would be a mystery to many English teachers today. And contemporary linguists might be unhappy with the syntactic analysis, not to mention the division of the language into ‘parts of speech’.

Some expositions rely on diagrammatic paradigms; personal pronouns are shown in three separate tables (1st person, 2nd person, 3rd person) that cross-tabulate Case (Nominative, Possessive and Objective) with Number (Singular or Plural), sometimes with separate columns for Gender (Masculine, Feminine, Neuter). Included in the tables are ‘thou’, ‘thy’, ‘thine’, ‘thee’, ‘ye’, ‘you’, ‘your’ and ‘yours’ (p. 35), a total of eight forms compared with only three in modern English. Thus, ‘If thou shouldst love’ (p. 63) is an example of the 2nd person singular ‘Future tense’ of the ‘Subjunctive mood’ .

The chapter on Syntax contains Parsing Charts like the ones below for ten word classes:

-

- Modern English Grammar:

- ‘State clearly the rules of English Accidence with regard to the use of shall and will in Assertive sentences.’ (p. 139).

- ‘Prove that vowel-change is not the decisive mark of the Strong conjugation.’ (p. 142).

- Idiom and Construction:

- ‘Explain and parse the following phrases:- methinks; woe is me; I had as lief.’ (p. 218).

- ‘Point out any grammatical errors that are common in ordinary colloquial speech. Say exactly what you understand by “good English”.’ (p. 219).

- Historical English: Word Building and Derivation:

- ‘What is a vowel? What vocalic sounds exist in modern English? Show particularly how they are all expressed by means of the six Roman vowels.’ (p. 423).

- ‘What traces of reduplication can you adduce in the tense formation of verbs in English (Old and Modern).’ (p. 428).

- Modern English Grammar:

Sources

Childs, W. M. (1933). Making a university: an account of the university movement at Reading. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd.

Nesfield, J. C. (1898). English grammar past and present. London: Macmillan.

Reading College. Calendar, 1898-99 & 1899-1900.