In a post of 7 September 2021, I mentioned that the Covid crisis wasn’t the first time that the London Road Campus had been closed because of an epidemic – in 1917 an outbreak of measles brought about a complete shutdown for two weeks at the end of the Lent Term.

The possibility of infection spreading across the campus and halls of residence continued to be a concern during the 1920s. This is illustrated by correspondence from February and March 1925 about students’ involvement in social work. The record of these is incomplete, but the gaps can be inferred from the five documents that remain.

It appears that a group of women students had been in contact with a Miss M. Maplesden, Secretary to the Reading Council of Social Welfare. They wished to carry out voluntary work in Coley, an area of social deprivation and overcrowding near the centre of Reading (see Ounsley, 2021). The students were advised to approach Professor Childs, Principal of the College, who requested that Miss Maplesden write to him formally. This she did on 24th February 1925.

Letter 1: Miss Maplesden to Professor childs

In her letter, Miss Maplesden made three main suggestions:

-

- that the students should join Domestic Science students who would already be observing social work in the neighbourhood;

- having found out what aspects of social work would be suitable, they would submit a plan for the following academic year to the Principal;

- the students should take responsibility for Coley Hall which had recently been offered to the Council for use on weekdays;

- in addition, she was in favour of the scheme being extended to include men students.

Letter 2: Miss Maplesden to Professor childs

The following day she wrote again to Professor Childs. From the content we can infer that they had already met to discuss the proposal, and that Childs had warned her that Hall Wardens were likely to be concerned about students bringing back infection from the Coley area.

Apparently, she had already informed her Executive Committee of the risk, and in an attempt to forestall such objections, she includes the following, rather baffling, justification:

‘Members of the Committee drew attention to the fact that during a period of epidemic the schools in crowded areas such as Coley, Greyfriars and Silver Street are as a rule less open to epidemics than the schools in better neighbourhoods.’

Memo 1: Professor Childs to the Hall Wardens

On the 3rd March 1925, Childs sent out a memo. It isn’t clear whether it went to all the wardens of halls and members of the two Hall Management Committees; on the typed copy in the University’s Special Collections, just five names have been added by hand:

-

- ‘bolam’ (Mary Bolam, Warden of St Andrews Hall – for women);

- ‘britton’ (Winifred Britton, Wessex Hall – for women);

- ‘Mrs. Childs’ (Emma Catherine Childs – wife of the Principal – Chair of the Committee for the Management of Women’s Halls of Residence);

- ‘Little’ (Emily K. Little, St George’s Hall – for women);

- ‘Cooke’ (H. S. Cooke, Cintra Lodge – for women: the only women’s hall with a male warden).

In the memo, he explained the situation and asked the wardens for their views. He warned that:

‘There are certain things which it is necessary to bear in mind, namely, the risk of infection and the general conditions under which the work is done.’

Childs received five replies; unfortunately only Letter 3 (see below) has survived.

Letter 3: Winifred Britton to Professor Childs

On 5th March 1925, Winifred Britton responded with a handwritten letter from Wessex Hall outlining her objections:

-

- there was too little time for the volunteers to shadow the domestic science students who were studying social welfare;

- ‘Coley is one of the poorest districts in Reading & the risk of infection would be great’;

- Coley was a long way from the College and time would be wasted travelling;

- ‘… it would entail students being absent from Hall dinner, a thing which is always discouraged.’

- there might be a lack of organisation, supervision and leadership;

- finally: ‘Also I do think that [the students] are inclined to forget the fact they are sent here to pursue a definite course of study which leaves very little time for outside activities.’

According to an interview conducted by J. C. Holt (1977), the relationship between Britton and Childs was a difficult one, and Britton resigned in 1929. I don’t know whether it was a factor in this case.

Letter 4: Professor Childs to Miss Maplesden

On the 18th March 1925, Childs sent a diplomatically worded letter declining the proposal. In doing so, he drew on several of Winifed Britton’s arguments. Nevertheless, he denied that risk of infection was a factor – after all, Education students were already doing teaching practice in local elementary schools. Instead, he suggested that the students could help run a summer camp.

‘Coley Talking’

The social history of Coley has been documented by Margaret Ounsley in ‘Coley talking: realities of life in old Reading’. Her chapter, ‘Talking of health, medicine, illness and death’, presents details of epidemics of measles, influenza, tuberculosis and diphtheria. To avoid too negative a picture, however, it is worth quoting part of the conclusion to that chapter, especially as it refers to the year of the Maplesden/Childs correspondence:

‘It would be wrong to give the impression that the population of Coley was completely disease-ridden. Undoubtedly, the poorest children were undernourished in the first few decades but by 1925 attendances at the Southampton Street Feeding Centre had dropped to eight. Many infants and children died, but also many people couldn’t remember having a day’s illness in their lives. The children for the most part seem to have led a hardy outdoor life with basic but nourishing food. Coley School won boxing, football and swimming trophies year after year in the 1920s and 1930s. There is no doubt that standards of health improved dramatically at this time.’ (Ounsley, 2021, p. 87)

Sources

Holt, J. C. (1977). The University of Reading: the first fifty years.Reading: University of Reading Press.

Ounsley, M. (2021). Coley talking: realities of life in old Reading. Reading: Two Rivers Press.

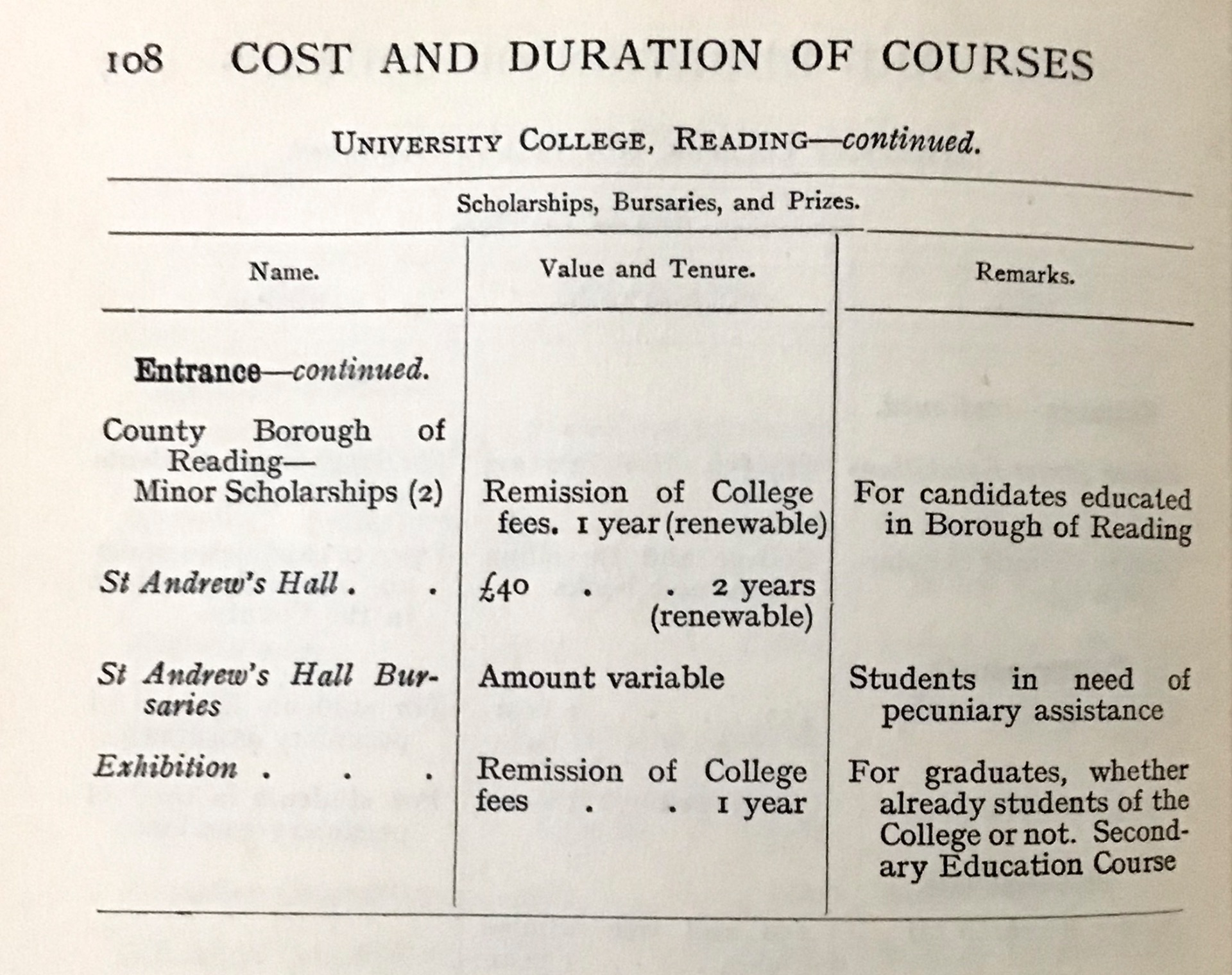

University College, Reading. Calendar, 1924-5.

University of Reading Special Collections. Uncatalogued papers relating to women students. Reference UHC AA-SA 8.