In the 1880s, before the University Extension College became Reading College and before the latter became a University College, research was taking place in the Departments of Science and Agriculture; regular supplements to the College Journal reported the results of agricultural field experiments.

Educational Research

The first records of school-based research did not appear until 1910-11:

‘Mr. Wolters has conducted some interesting experiments at the Demonstration School with regard to Child Study; and Mr. A. W. Seaby tried some experiments with the older boys in drawing and design work. A short experimental study of fatigue in school was made by students preparing for the London University Examinations in Education.’ (Report of the Academic Board, 1910-11, p. 41)

The names Wolters and Seaby will be familiar to readers of this blog. Albert Wolters went on to found the Psychology Department and was Deputy Vice-Chancellor between 1946 and 1950; Allen Seaby became Professor of Fine Arts in 1920, and was Departmental Director from 1911. Both contributed to Teacher Education programmes and had experience teaching children (Wolters had qualified as an Elementary School teacher at Reading).

The ‘Demonstration School’ was Redlands School, and its three headteachers, including Eliza Chattaway, Head of Infants (see earlier post about the Farm School), were members of the College’s Teacher Education section. Redlands became a convenient focus for research activity, as shown by a report in the College Review under the heading of ‘Educational Experiments’.

Three such experiments were conducted in the Demonstration School ‘and other selected schools’:

-

- Spelling: the relative success of class teaching versus private study in learning spelling (instruction was twice as effective at all ages).

- Imagination: children were given the beginning of a story that they were asked to complete. It was found that girls tended to describe scenery, whereas the boys focused on actions. We are told that, ‘The London boys occasionally referred to common incidents of life in town, while the provincial children kept exclusively to Fairyland.’ (p. 22).

- Memory: ‘A hundred boys were made to learn a series of twelve numbers, the number of readings required to obtain a correct repetition being noted. It was found that there was great improvement between the ages of seven and ten and practically no improvement later.’ (College Review, 1910, p.22)

The Logbooks of Redlands School show that, following the creation of a Senior Mixed Department in 1929, University Education staff immediately requested further collaboration and, within weeks, a certain Miss Campbell (Lecturer in Education – see below) arranged for her students to administer intelligence tests in the lower part of the school.

Further information about educational research is hard to find. Projects probably took place that never found their way into College documents. I can find no evidence of any ‘experiments’ being published. Nevertheless, according to H. Armstrong’s overview of the history of the Education Department:

‘Investigations in teaching methods by members of the Education Staff were an important feature from the earliest days. It is interesting to record here an example of experimental work done by students themselves. Early in 1923, at St. John’s Schools, students tried out the Dalton Plan.’ (Armstrong, 1949, p. 15)

The Dalton Plan was a progressive scheme of learning designed by Helen Pankhurst in the USA. There was no formal class teaching; pupils worked at their own pace and designed their own timetables. The students at Reading concluded that:

‘…. class teaching must retain its decisive place in school administration, and could not be put aside.’

This and other ‘experiments’ raise questions about the extent to which the students were given free rein, how it was negotiated with the school, what preparation they received, and how parents, children and regular class teachers felt about it! Did anyone think about ethics?

Publications

The first list of staff publications appeared once the original College had acquired the status of University College, Reading. The list was published in the Official Gazette in 1903, and contains just 9 academic publications by 5 staff in the Letters and Science Departments, followed by a set of Technical Reports, mainly from Agriculture (e.g. ‘Practical Buttermaking’ by Mr Edward Brown). But it does also include an item titled ‘Blackboard Drawing’ by Allen Seaby (see above). This is the first record of a published contribution to the field of Education.

Subsequently, lists of publications appear only intermittently with Agriculture figuring prominently (‘The Value of Poultry Manure’ by Edward Brown & W. Brown, 1907).

In 1906, however, Education was represented again: W. G. de Burgh, Lecturer in Philosophy and Classics, published ‘The Development of Individuality in the Young: an Address to Students of Education’ in the ‘The Parents’ Review’. (Burgh became Dean of the Faculty of Letters in 1907 and was Deputy Vice Chancellor of the University from 1926 to 1934).

De Burgh wasn’t the only member of the College to publish in The Parents’ Review. In the Annual Report for 1909-10, H.S. Cooke, Lecturer in Education (later Master of Method and Head of Department), was author of ‘The Real Meaning of Children’s Play’.

‘The Parents’ Review’ described itself as ‘A Monthly Magazine of Home-Training and Culture’ and, between about 1890 and 1920, was distributed to parents and teachers engaged in homeschooling .

The following is an illustrative sample of publications relating to Education, set out as they appear in the Annual Reports:

-

- 1909-10: ‘Mr. Cooke:- “School Practice Guide and Instructions” (C. Elsbury, Reading).

- 1911-12: The Principal [W. M. Childs] .. .. “The Essentials of University Education.” (Hibbert Journal April, 1912).

- 1911-12: Professor de Burgh .. .. “The Use and Abuse of Educational Theory.” (Parents’ Review), March and April, 1912).

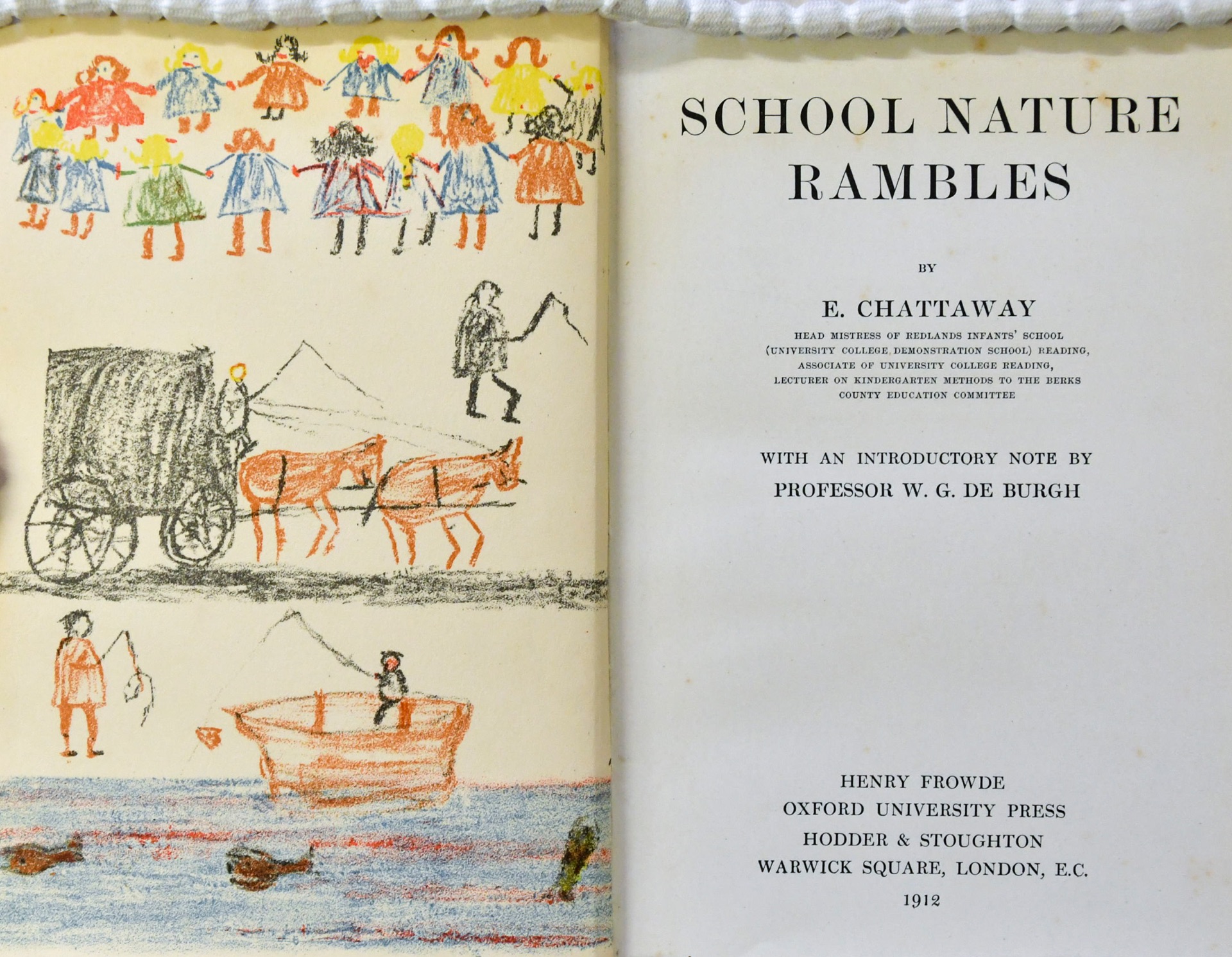

- 1912-13: Miss Chattaway .. .. “School Nature Rambles.” (Oxford Elementary Schoolbooks, 1912, pp. 221).

- 1913-14: Professor Edith Morley “Teaching as a Profession for Women.” (Educational Times, June, 1914).

- 1918-19: Professor Edith Morley … The Teaching of English. A Series of Papers read at a Conference at University College Reading, July, 1918. (Pamphlet 43 of the English Association).

Between 1903 and 1926, the year of the Royal Charter, just six members of staff produced literature on the theme of Education – a total of 17 publications. These were mainly practical guides or opinion pieces. None involved involving data collection and analysis, although Eliza Chattaway’s book is a (probably idealised) record of a year’s nature study with the children at Redlands Infants’ School.

Three of the contributors were based outside the Education Department. Of these, Edith Morley, as the most prolific, deserves a special mention. Over the course of this period, in addition to her research on English Language and Literature, she developed a reputation as an expert on the Teaching of English and organised a conference on the subject that took place in the Great Hall in July 1918. It was attended by over 300 people and was reported in the Journal of Education and The Times Educational Supplement. She edited the Volume of Proceedings that can be seen in the illustrative sample above.

Such was Morley’s interest in English teaching that two years later the Report of the Academic Board reported that:

‘Professor Morley gave evidence before the Government Commission appointed to report upon the study and teaching of English Language and Literature.’ (p. 14).

The outcome of this was the Newbolt Report of 1921 (see note below) in which Morley is mentioned as an Individual Witness.

On Becoming a University

The University took a more rigorous approach to recording publications. From 1925-6 onwards, the annual Proceedings combined the list of publications across departments and it contained only items that had been approved by the Research Board. The list is in three sections: I. Books; II. Articles embodying Results of Original Work; III. Other Publications. The list is longer than ever before, raising questions about how complete the earlier College lists had been.

We also find the first indication of a research grant for education from University funds: E. Smith received £20 ‘for travelling expenses incurred in connexion with researches on the history of English education between 1660 and 1714’ (Proceedings, 1925-6).

The following year, Isabella Campbell (see above) was awarded £15 ‘for travelling expenses incurred in consulting literature bearing upon her research on temperament tests’. In 1943 Campbell became the first lecturer in the Education Department to obtain a PhD on ‘A study of abstract thinking and linguistic development with reference to the education of the child of ‘average’ intelligence.’ In the same year, Charles Rawson became the first Education student to be awarded a doctorate for his work on the WWII evacuation.

Such events had been predicted by an article by Childs in Tamesis in 1926 which considered the implications of becoming a University:

Educational Research Today

These humble beginnings may seem a far cry from the achievements of the present Institute of Education. Nevertheless, thanks to the work of early pioneers, particularly those like Isabella Campbell and Albert Wolters who crossed disciplinary and departmental boundaries, a tradition was established that led to today’s internationally recognised research programme, with its valued contribution to theory and practice across the education, language and learning spectrum.

Note

The Newbolt Committee and its Report were named after its chair, Sir Henry Newbolt – a historian, novelist, poet and adviser to the Government of the day.

The Newbolt Report was often quoted by educationalists and linguists when Michal Gove, Secretary of State for Education (2010-2014), reformed the English curriculum for Primary Schools and Introduced tests of Spelling, Grammar and Punctuation (SPAG). A particular favourite of those opposed to the reforms was Newbolt’s reference to the unpopularity of grammar as the most hated part of the curriculum – an inspector’s report of 1894 is quoted, stating that, ‘English Grammar has disappeared in all but a few schools, to the joy of children and teacher.’ (Para. 51)

For the benefit of cricket lovers: in his role as poet, it was Sir Henry Newbolt who penned the famous line, ‘Play up! play up! and play the game!’

Sources

Armstrong, H. (1949). A brief outline of the growth of the Department. In H. C. Barnard (Ed.), The Education Department through fifty years (pp. 9-17). University of Reading.

Board of Education (1921). The teaching of English in England [The Newbolt Report]. London: HMSO.

Childs, W. M. (1926). Our University. Tamesis, Vol. XXV. No. 7. Summer Term, pp. 83-6.

Holt, J. C. (1977). The University of Reading: the first fifty years. Reading: University of Reading Press.

Rooke, P. (1991). Redlands: a hundred years at school, 1891-1991. Reading: Redlands School Parents’ Teacher Association.

The Journal of the University Extension College, Reading, Vols 2 & 3, 1895-96 & 1896-97.

University College, Reading. Accounts and Annual Reports, 1906 to 1925.

University College, Reading. Official Gazette. No. 31. Vol. II. 10th December, 1903.

University College, Reading. Official Gazette. No. 51. Vol. V. July 3, 1907.

University of Reading. Proceedings of the University, 1925-26 & 1926-27.