‘Writers must learn pretty quickly to disguise what they’re doing if they don’t want to end up in the libel courts.’ (Val McDermid, 2023)

My previous post about Elspeth Huxley dealt with her time at Reading as it was portrayed in the book, ‘Love among the Daughters’. Her description of Reading and the London Road Campus was far from flattering.

The reviews and notices of the work label it ‘non-fiction’ even though it bears many characteristics of a novel. In the Evening News of 26th Sept. 1968 it was already listed fourth in the non-fiction best sellers; the following month it was ranked first, ahead of Kim Philby’s ‘My Silent War: the Autobiography of a Spy’ (there are those who claim that this contained elements of fiction, too). And in an interview with The Times on 16th September 1968, Huxley described it as autobiography. Nevertheless, it is generally regarded as an example of ‘fictionalised autobiography’, a genre in which changes to details of real people, places and events do not detract from the authenticity of the account.

There are several reasons to question the accuracy of the narrative:

-

- a gap of over 40 years between the events described and publication;

- changes calculated to avoid offending people who were still alive;

- exaggeration and caricature for comic effect (the humour is a recurring theme of the book reviews; Christine Nichols, Huxley’s biographer, regarded it as one of her wittiest books);

- Huxley’s own statements about her recollections;

- discrepancies with historical records.

In August 1968 Huxley was interviewed on BBC Woman’s Hour by Marjorie Anderson. Here she gave a far more nuanced explanation of ‘autobiography’ than in her Times interview:

‘Well, it’s an autobiography in a sense, but it’s more of a recreation, more of a reconstruction of the period and of the impressions one had of life at that age than it is a chronological series of actual events. I don’t pretend to remember conversations which one had forty years ago, so one recreates the conversations, trying to make them true to the people one was conversing with – I mean one tries to create the atmosphere, but it’s much more of a creation of atmosphere than a chronicle.’ (Recorded 9th August 1968; broadcast 18th September 1968).

She further revealed that she never kept a diary but did have some notes that she made at Cornell and some old photographs.

Huxley’s Family

Elspeth stayed with her aunt, uncle and cousins on arrival in England and during the vacations. Although these periods have little relevance to her time in Reading, the treatment of her relatives illustrates her approach.

Gertrude, Kate and Joanna are the children of Aunt Madge and Uncle Jack. They are Elspeth’s cousins and ‘the daughters’ of the book’s title. All the above names are pseudonyms, as is the case with other relatives and acquaintances.

Cousin Gertrude is a superficial 1920s flapper; Kate got herself expelled from her convent school for various crimes such as running a book on racehorses; Joanna, the youngest, attends a ‘smart’ school in Suffolk; Aunt Madge descends into weeks-long silent sulks; and the idiosyncratic, bigoted Uncle Jack seems angry, disapproving and withdrawn except when reminiscing about his regiment.

These caricatures are accompanied by other family members such as Aunt Lilli and Uncle Rufus (a less well-suited couple it is hardly possible to imagine), not to mention the bottom-pinching Lord Fulbright who insists on taking young women skating, and the withered Russian countess with a constipated parrot that attacks people’s ankles.

It is in such stereotypes, and those of some of the personalities at Reading, that much of the humour lies. It must be said, however, that some of the witty features that thrilled the critics of 1968 are far less hilarious for the modern reader – Lord Fulbright comes across as a sinister predator rather than an amiable eccentric; the casual racism and antisemitism in language and attitudes, the snobbery and patronising colonial attitudes, even if they accurately reflect and satirise the views of a particular section of society in the 1920s, can still come as a shock.

In ‘Elspeth Huxley: a biography‘, Christine Nicholls documents the extent to which changes had to be made to avoid offending living family members. In particular, the real-life Joanna didn’t want her daughter to know about her youthful indiscretions. Joanna’s adventurous character was therefore transferred to Kate, and references to drugs, illegitimacy and an abortion were deleted.

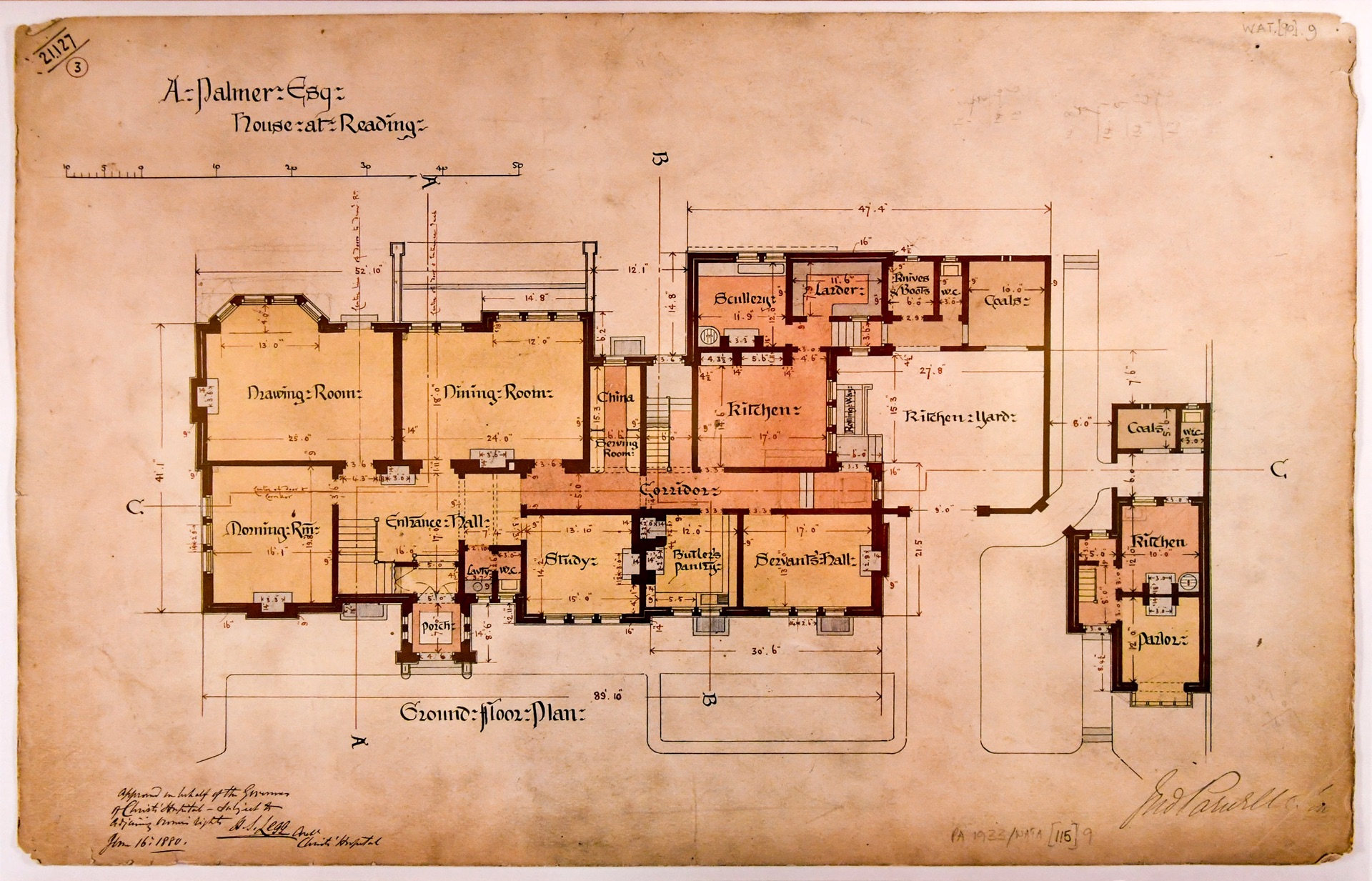

Reading and the College/University

In his master’s thesis, Richard Keefe confirms some details in the book, but also notes factual errors: the number of Women’s halls of residence, the size of the student population and the ratio of male to female students. Huxley claimed that ‘Girls were in the fortunate position of being heavily outnumbered by men’ (p. 48), whereas in fact the opposite was true. This misconception, which was perpetuated in the book reviews, and even her biography, must have resulted from Huxley’s experience among predominantly male Agriculture students.

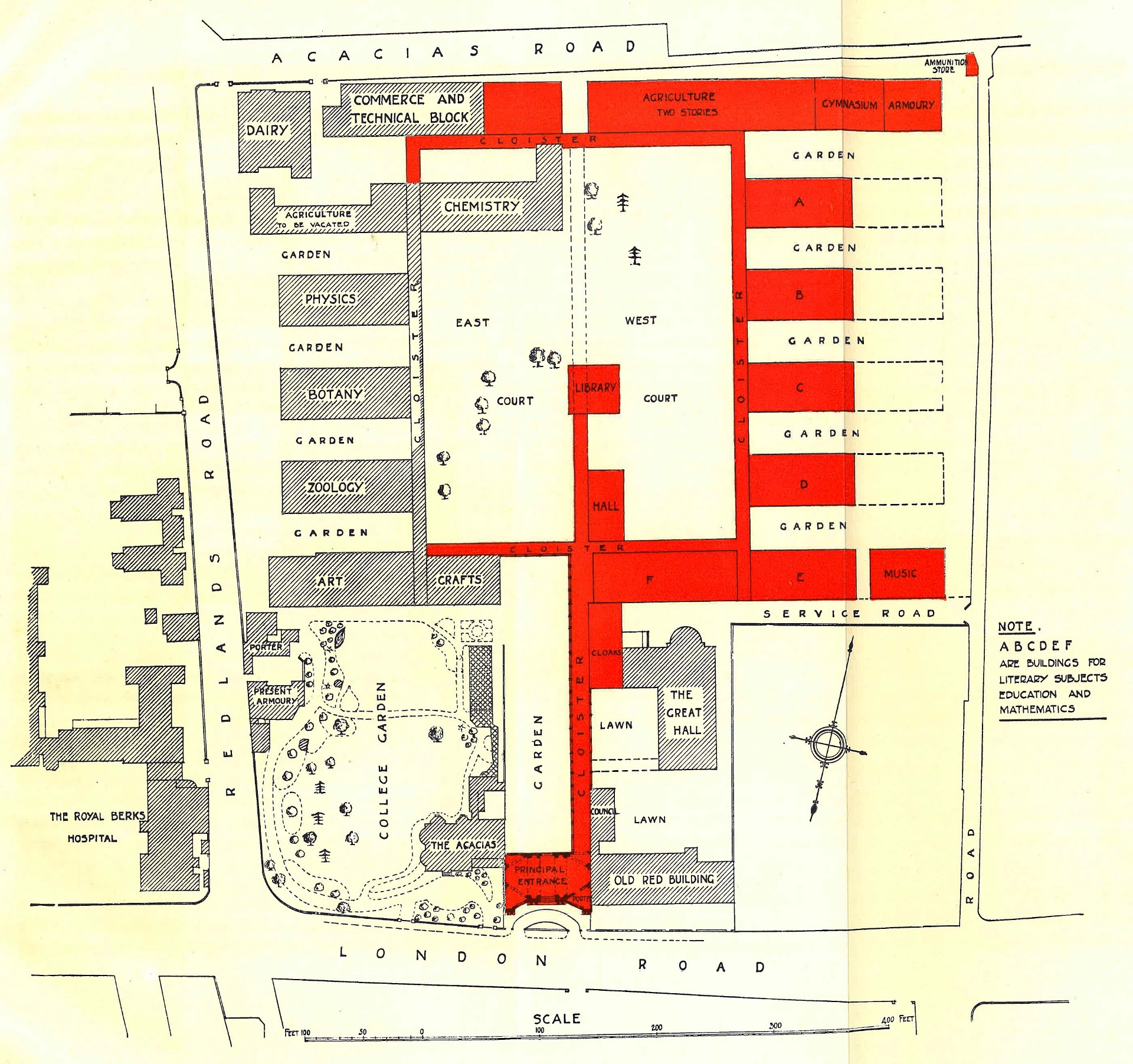

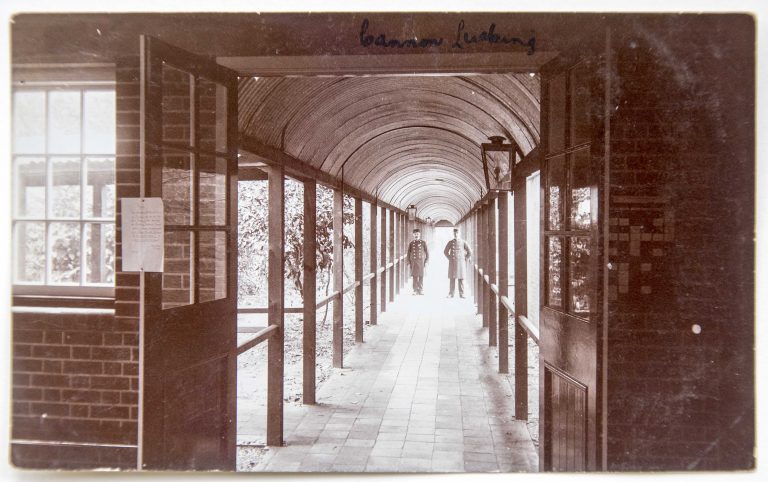

Elspeth’s gloomy perception of the campus and its buildings contrasts sharply with that of Edith Morley (‘These extensive and beautifully laid out grounds’, 1944/2016, p. 111) and with the ambition of W. M. Childs, Reading’s first Vice-Chancellor, ‘to make a place of sojourn for impressionable youth’ (1933, p. 51). In his history of the first 50 years of Reading University, J. C. Holt (1977) concludes that Huxley’s views could be neither ignored nor dismissed – an objective judgement was impossible.

However, in the BBC interview, when Marjorie Anderson queried the dreariness of Reading and the wisdom of educating young people in dreary surroundings, Huxley appeared to attribute this to the town rather than the University:

‘Oh I don’t think I found it dreary myself. I thoroughly enjoyed it.’

Huxley’s Fellow Students

The pseudonyms of the students who figure most centrally are:

-

- Dando: female, a Dairying student who played lacrosse;

- Thomas: male ‘an athlete and a hockey star’, Dando’s friend;

- Snugg: female, a third-year student, housemate of Huxley;

- Turner: male, Rugger Captain, Snugg’s friend;

- Corbett: male, Cricket Captain;

- Viney: male, captain in the Officers Training Corps, and member of the University’s rowing eight;

- Swift: female, Fine Arts student, housemate of Huxley;

- Abdul: male, studying Commerce, Swift’s friend, described as ‘a swarthy, sleek-haired Oriental of some kind’, p. 59); the only foreign student, and the only student referred to by his first name;

- Nash: male, member of the Dramatic Society and Labour Club – an outsider because of his politics and background.

Thomas, Turner, Corbett and Viney made up the self-styled Philosophers Club, an all-male clique who ‘sat together in the Buttery, drank together in the pub, … shared a boat on the river, [went on] jaunts to London to see a show.’ (p. 53).

Following a careful analysis of student records and having spotted how Huxley transposed letters in people’s names, Richard Keefe is confident that he has identified the students on which the characters of Snugg and Turner were based.

Of Snugg, Huxley writes that she:

‘… gave herself airs, and was apt to introduce into conversations topics like hunt balls, point-to-points, first nights, presentations at court and cousins in the Foreign Office’ (p. 51).

All of which was greeted with scepticism because she came from Birmingham. Richard Keefe suggests that the real Snugg was Marjorie Hope Scutt, born in 1906, a student of Fine Art (Diploma), Embroidery (Certificate) and Leatherwork (Certificate).

Huxley sums up Turner as:

‘… not only lord of the [Rugby] Fifteen but he was reading agriculture, had a job lined up in the colonies, held office in the Students’ Union, and was said to drink a lot of beer ; so he was one of the social princes. (p. 50).

Turner was due to spend the next year in Trinidad as training for the Colonial Service and is identified by Keefe as George R. Parker, a Wantage Hall student (1924-26).

Turner’s intended career seems typical of what Huxley claims for the majority of agriculture students at Reading – they would never dirty their hands ploughing or hoeing, but would join local authorities or become agricultural officers and District Commissioners somewhere in the Empire, enjoying the benefits of servants, plenty of leave, good pay and a generous pension after only 25 years.

The Academic Staff

While it takes detective work to identify the students in the book, Huxley’s lecturers in the Agriculture Department are immediately recognisable. One, Professor Sidney Pennington, is even mentioned by his real name – there was no need for a pseudonym because she held him in high regard – he was a practical person who could turn his hand to real farm work. This should not surprise us as, before his promotion, the College had appointed him farm manager in 1914.

One observation that finds an echo in the University’s Photographic Collection is that ‘the professor was accompanied everywhere by a small and shaggy white terrier’ (p. 69).

Huxley’s other lecturer was ‘Our Dean’, unnamed but obviously H. A. D. Neville, professor of Agricultural Chemistry and Dean of Agriculture since 1920. He is not named in the book, presumably because his description is less complimentary:

‘… a small, squat, ugly, rather savage Midlander who taught biochemistry, spitting out the formulae as if they had been so many oaths …’ (p. 116).

The Intermingling of Fact and Fiction

According to Huxley’s biographer, the detail in ‘Love among the Daughters’ cannot be entirely trusted:

‘What Elspeth did was to portray locations accurately, but conceal the truth about events and people who were still alive. She would often transfer a remembered incident to a different time, and always amalgamated or distorted characters so that there was no danger of libel.’ (Nichols, 2002, p. 82)

Nevertheless, as Antonia Fraser suggested in the Sunday Times (22nd September 1968), Huxley skilfully negotiated the blending of fact and fiction such that the reader understood far more of the social history of the period than through academic study.

Acknowledgements

The BBC copyright content is reproduced courtesy of the British Broadcasting Corporation. All rights reserved.

Thanks also to Penguin Random House for permission to access the Review File for ‘Love among the Daughters’ and to use the quotations from the Woman’s Hour interview.

Many thanks to Richard Keefe for giving me a copy of his master’s thesis.

Sources

Childs, W. M. (1933). Making a university: an account of the university movement at Reading. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd.

Holt, J. C. (1977). The University of Reading: the first fifty years. Reading: University of Reading Press.

Huxley, E. J. (1968). Love among the daughters. London: Chatto & Windus.

Keefe, R. (2022). History, Big Data and changes in the University of Reading / University College Reading’s Student Population over time (1908-1972). Unpublished Master’s Thesis, University of Reading.

McDermid, V. (2023). Past lying. London: Sphere.

Morley, E. J. (2016). Before and after: reminiscences of a working life (original text of 1944 edited by Barbara Morris). Reading: Two Rivers Press.

Nichols, C. S. (2002). Elspeth Huxley: a biography. London: Harper Collins.

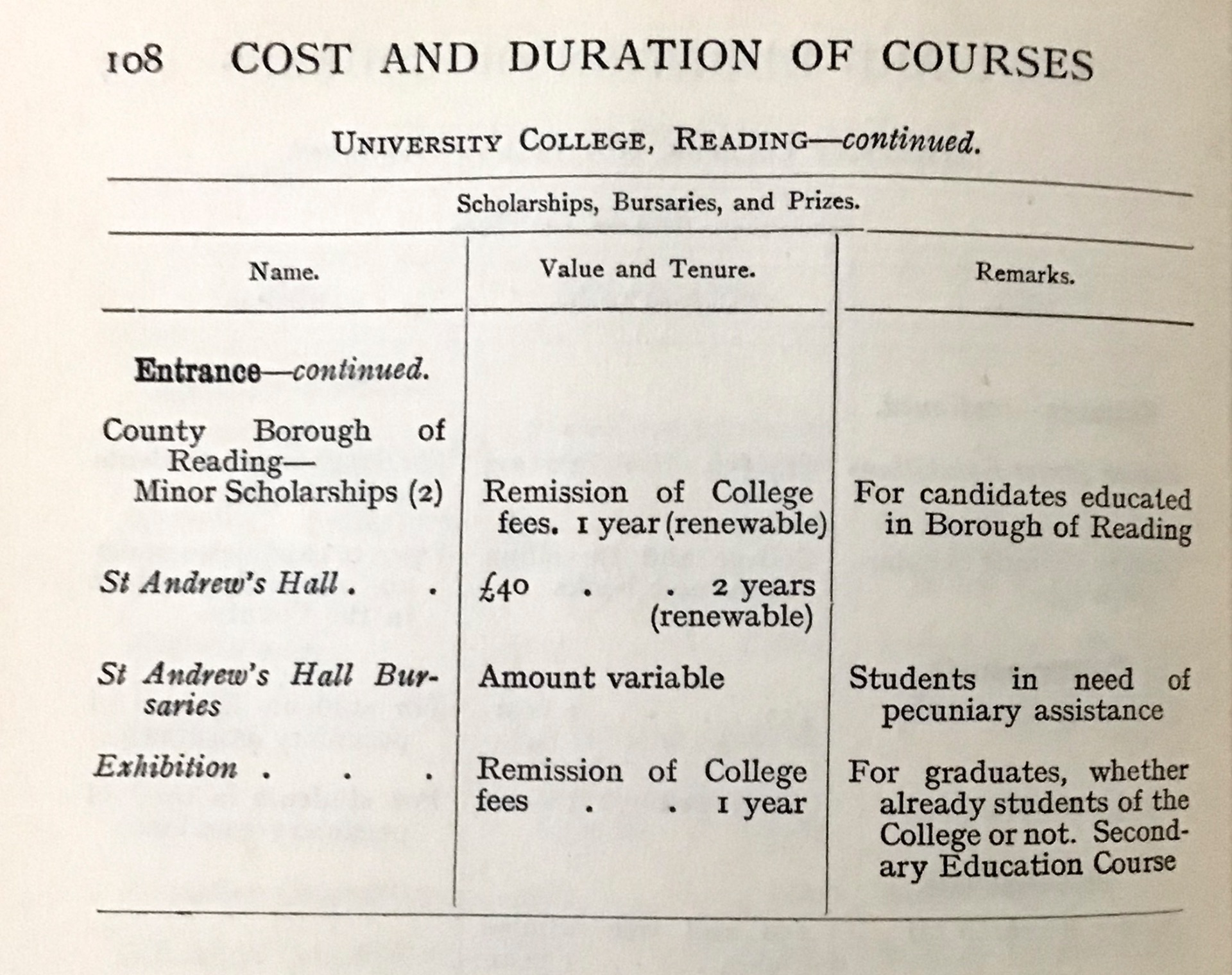

University College Reading, Calendar, 1925-6.

University of Reading, Calendars, 1926-27 & 1927-28.

University of Reading Special Collections. Review file for ‘Love among the Daughters’ by Elspeth Huxley. Reference number: CW R/4/40 [also containing interviews with the author and BBC broadcasts – BBC copyright content is reproduced courtesy of the British Broadcasting Corporation. All rights reserved].

University of Reading Special Collections. University History MS 5305 Photographs – Portraits Boxes 1 & 2.