‘The notion that an art student is a reckless creature, unable to handle any implement other than a pencil or brush, is sternly discouraged.’ (Article about Fine Arts at University College, Reading, Every Woman’s Encyclopædia, 1910, p. 2838)

This blog recently described the buildings and location of the Department of the Fine Arts on the London Road Campus. At times, it has also mentioned members of the Fine Arts Department such as Robert Gibbings, the celebrated wood engraver, underwater artist and travel writer, and Allen W. Seaby.

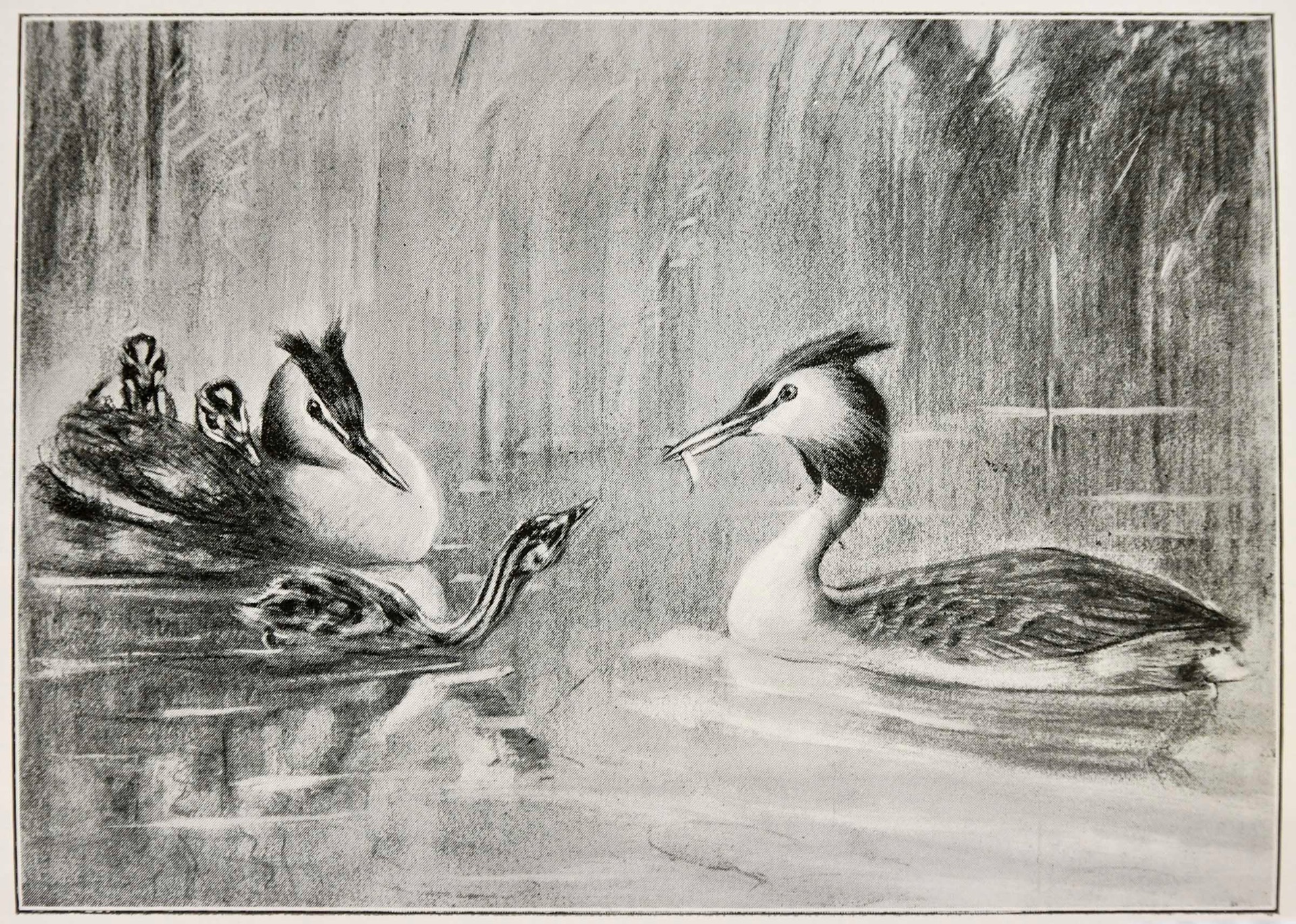

This post looks at the Department in 1910 when Seaby was still a lecturer. though he was soon to become Director of the Department and eventually Professor of Fine Art. A product of the Department himself, having obtained his Diploma in 1903, he made an impressive contribution to the culture of the College and University. Previous posts have referred to Seaby’s design of the bookplate for St Andrew’s Hall, his early educational research, the picture of the Great Hall by moonlight, sketches of the grebes on Whiteknights Lake and his participation in the Farm School.

An Encyclopaedia Entry

In 1910, Every Woman’s Encyclopaedia published a four-page entry about Reading’s Fine Arts Department.

The article must have been a triumph of publicity for both the College and the Department. Information was provided about fees, hostels for women students (‘the dietary is under medical inspection’) and staffing of the Department. There was praise for the well-stocked library and attention was drawn to the athletic ground and the common room where art students socialised with those studying a wide range of other subjects. The way that Fine Arts was successfully integrated within a well-developed higher education programme was described as ‘unique’.

One advantage of this was that art students had access to classes in other subjects. It also supplied them with a wide variety of subjects to draw and paint. Horticulture and Botany, for example, provided facilities for the flower painter and, ‘The animal painter … has access to the zoology professor and his museum’ (p. 2839; i.e. the Cole Museum).

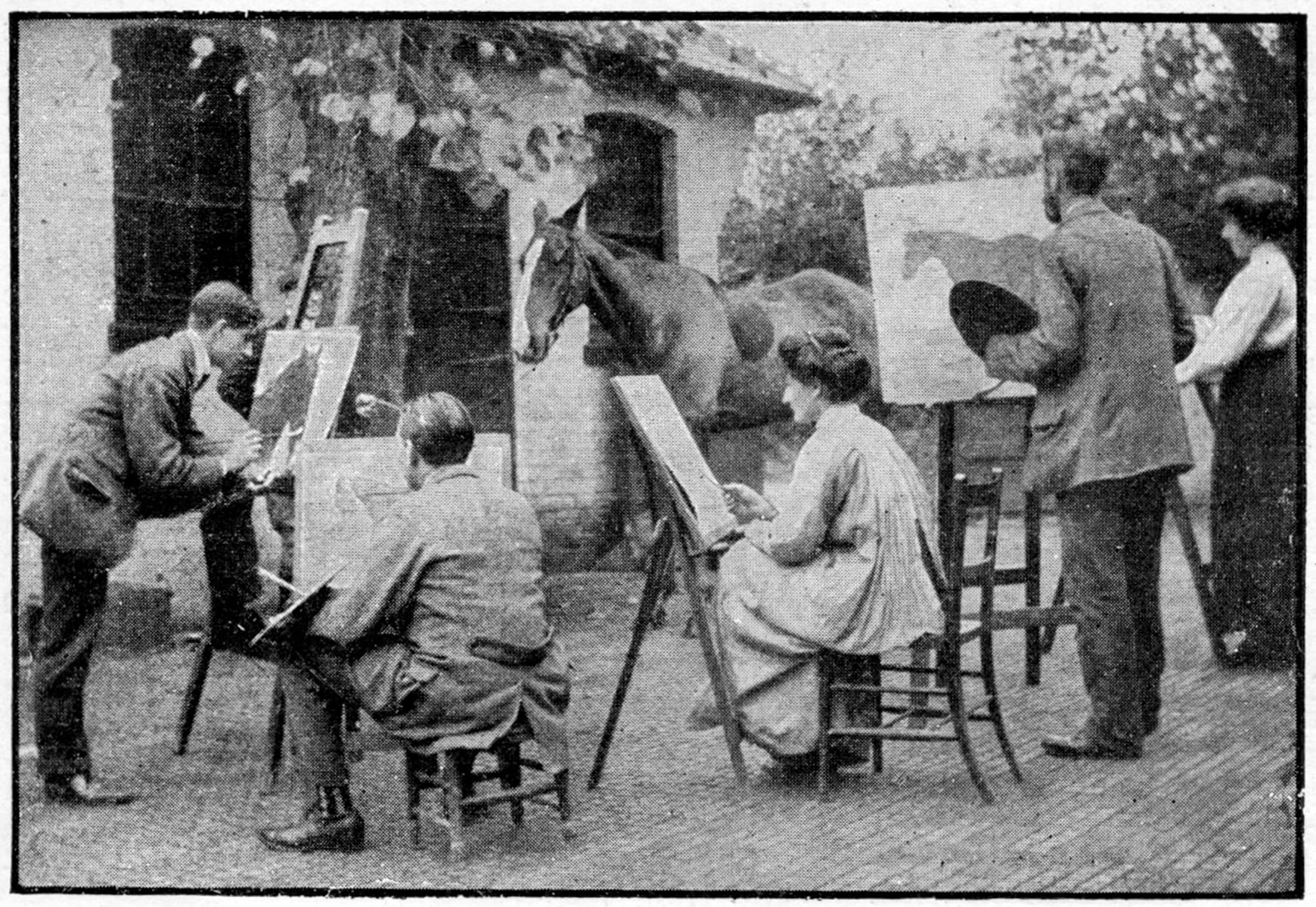

Using animals, even horses, as subjects obviously formed a highly significant part of the Department’s work:

‘The study of animal painting and modelling from life is another branch of the training. A collection of small animals and a number of birds are kept specially on the premises to act as models. They are placed in pens on the grass in the centre of the class on sunny days, and, in bad weather or in winter time, in cages in one of the studios.’ (p. 2840)

The curriculum included life classes that used professional models from London, and there was an emphasis on drawing from memory. One drawing-based craft such at etching, illuminating or colour printing was compulsory. Apparently, Reading was one of the rare institutions that taught colour printing using wood blocks. Other crafts included stained-glass work, artistic metalwork, leather work, wood carving, bookbinding and embroidery.

One thing that seems strange is that allowing students to use colour rather than just drawing in black and white was apparently rather daring:

‘The more elementary students are often allowed to express their ideas of objects placed before them in colour, and as is now slowly being recognised, such colour exercises keenly stimulate their sense of form.’ (p. 2839)

Of particular importance was the fact that the Department was recognised by the Board of Education as a centre for teacher training. As well as the Department’s own Diploma, therefore, students could qualify as art teachers in primary or secondary schools. It also gave them access to prizes and scholarships offered by the Board.

The entry provides a broad and entirely positive overview of the Department. There are inaccuracies, however – a minor but understandable error is the confusion between the University Extension College (formed in 1892) and University College, Reading (1902). What must have been more annoying at the time is the misspelling of Allen Seaby’s name as ‘Sealy’.

One discrepancy that I can’t explain is that Seaby, rather than Professor Collingwood, was described as Director of Fine Arts. According to the annual report for 1910-11, however, Seaby was not appointed Director until Collingwood’s resignation at Easter, 1911. All the other members of the Department who were listed in that year’s Calendar were mentioned in the article, including Walter Crane the Visiting Examiner.

The Curriculum as Presented in the College Calendar (1910-11)

The Calendar contains details of the scheme of work, the classes available, and regulations for the Diploma in Fine Art and Certicates in the various Crafts.

The curriculum was organised under groups of studies:

-

-

- Drawing, Painting and Modelling.

- Architecture.

- The Artistic Handicrafts.

- Design.

- Methods of Teaching.

-

To qualify for the Diploma, students had to follow courses for no less than nine terms and perform satisfactorily in three out of five of the following: Drawing, Modelling, Painting, Design and Composition. In addition, they had to pass an examination in one subject from the Associate Examination in Letters and Science which they attended for one session.

Certificates courses lasted one session and were available in Metalwork, Wood Carving, Emboidery and Leather Work.

The School of Art’s New premises in 2023

In 1910 Fine Art was located in Building L4 at London Road, where Art Education can still be found today.

In the mean time, the University of Reading’s School of Art has come a long way from the original Department of Fine Arts. In 2023 it moved from Earley Gate to purpose-built premises close to the Pepper Lane entrance to the Campus.

Thanks

To Richard Keefe for passing on the extract from Every Woman’s Encyclopaedia.

Sources

University College, Reading: the Fine Arts Department. Every Woman’s Encyclopaedia, Vol. 4, 1910, pp. 2838-2841.

University College, Reading. Calendars, 1909-10 to 1911-12.

University College, Reading. Report to Council, 1911.