As far as we can tell from census records, Mary Ann Bolam was born in Rainton Bridge, Durham, in 1862 and was the daughter of Thomas Bolam, a wagon wright for the local colliery who later became a grocer. She had a younger sister named Susannah, a dressmaker, who was born in 1864.

We know little about Bolam’s early education but in his history of the first 50 years of Reading University, Holt (1977) points out that she was a member of Summerville College at a time when women could not be accepted to an Oxford University degree. She graduated with honours in History (4th class) and received her first degree from the University of Dublin.

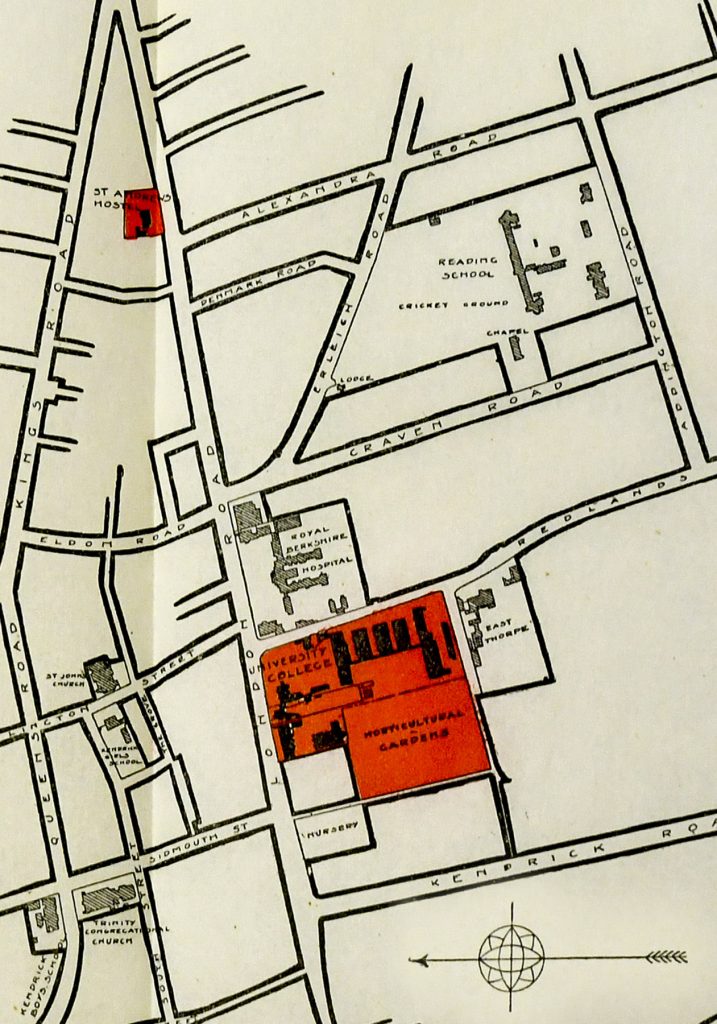

There followed a Teacher’s Certificate from the Board of Education, and a Diploma in Education and Geography from the University of St Andrew’s. Before taking up her post at Cheltenham Ladies’ College in 1897, she was Mistress of Method at Durham Training College and taught at a Demonstration School nearby. She moved to Reading in 1900 and remained in post until 1927.

Retirement

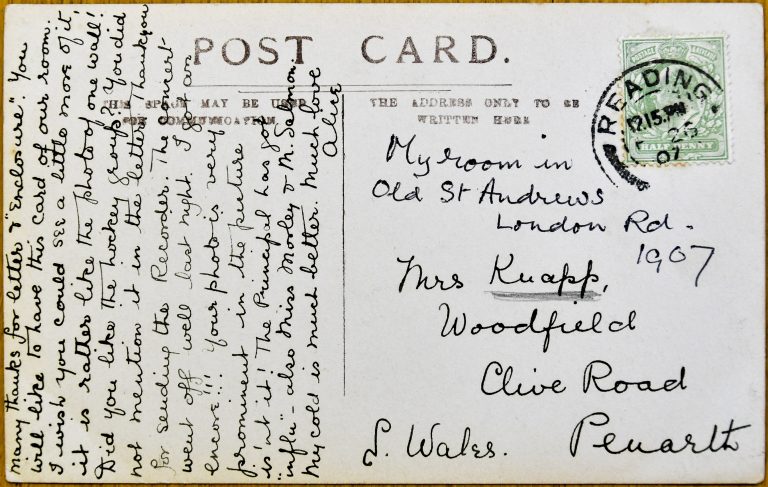

On her retirement in December 1927, the Reading Standard reported an official presentation to her in the University’s Buttery at London Road. It was attended by 120 of St Andrew’s Hall students, past and present. She received gifts of a silver coffee and tea service and a cheque. A framed portrait of her was presented to Mrs Childs by the chair of the St Andrew’s Students’ Committee so that it could be given a permanent place in the hall. In my previous post I mentioned that Holt had described Bolam as a ‘living legend’, and there were many similar accolades now (‘Obstacles that would have crushed the spirit of a less brave woman seemed to make Miss Bolam grow younger.’ – Reading Standard, 10/12/34, p.10). Professor Childs wrote a glowing testimonial in Tamesis that concluded:

‘Her fame with us is secure ; for no one else in this University can ever do again pioneer work of the same kind.’ (Childs, 1927, p. 210).

After retiring she lived at 30a Northcourt Avenue. The house was built in 1927. It lies on the opposite side of the road from Wellington Avenue and still bears its original name: ‘Four Ways’.

It is said that Mary Bolam’s students presented her with a particularly fine front door, which she promised would always be open to them (Kemp, 1996). An article in the Reading Standard from 1944 in honour of her 85th birthday showed her to be still living at ‘Four Ways’. It claimed that her students had helped her to build it in gratitude for all she had done – this seems a slight exaggeration, however; the builders were J. H. Margetts & Son (Kemp, 1996).

Bolam’s great-nephew, Stanley Phalp

There are few details available about how Mary Bolam spent her retirement. At one stage, she was a member of the Governing Council of Kinmel School, Abergele, North Wales, from which she resigned in 1929 – the Council had never met and the school never drew on her expertise.

Nor do we know exactly when and why she left Reading. According to the Northampton Mercury, she died at the age of 88 in Weston Favell, Northampton, on November 30th 1949 and left the sum of £1,792 10s. 8d.

One interesting detail to emerge from newspaper articles of the time, however, is that in the 1930s she was either the tenant or owner of Pond Wood Farm, Billingsbear, near Wokingham (now replaced by housing). It seems that she had taken over the farm for the benefit of her great-nephew, Stanley Phalp, who was given the role of manager.

Stanley had been born in 1911 and was the grandson of Mary Bolam’s sister Susannah. His father, Norman Thomas Bolam Phalp, had been incapacitated in the 1914-18 War, and from the age of seven, Stanley was in the care of his great-aunt. He was known to some Reading students from spending his summer holidays at St Andrews Hall, and in 1928 he enrolled as a student in Reading University’s Faculty of Agriculture.

Stanley’s Suicide in 1934

Stanley Phalp died on the 29 September 1934. The first press reports of the circumstances of his death appeared a few days later on 3 October.

He had been spotted in a semi-conscious state in his car on Saltpit Road, Hurst, near Reading. A doctor had been called but death could not be prevented. There was a lengthy police investigation.

Stanley’s father was interviewed, but he knew little about Stanley’s private life or finances, other than that he was in perfect health, a non-smoker and a teetotaller. The Coroner established that Stanley lived with Miss Bolam, but that he was of age and therefor not in her charge. Because a post-mortem had failed to reveal the cause of death, the Coroner adjourned the inquest and ordered a forensic examination of the organs by a county analyst.

Arsenic poisoning was confirmed – according to the Public Analyst, more than five times the fatal dose had been extracted from the stomach contents. The press revealed that police had discovered a bottle of weedkiller and a letter from a woman in London who had turned down Stanley’s proposal of marriage.

The inquest was resumed on October 13 and the jury returned a verdict of suicide. Mary Bolam gave evidence. She produced a letter from Stanley that she had found in her desk, and gave details of a phone call he had received from a Miss Joan Rich whom he had known for several years and who had been expected to come and stay. Stanley had then left in his car, presumably having already ingested the poison.

Mary Bolam said that Stanley had seemed in good spirits that day, ‘His heart and soul were in his work at the farm and he worked from morning until night.’ (Coventry Evening Telegraph, 3 Oct 1934, p. 1).

The case was reported in detail, both locally and nationally, paying particular attention to his relationship with Miss Rich, their letters to each other, the content of the phone call, and the nature of the poisoning. Bolam had clearly been upset by being taken to view the body in the car; and she was incensed by the lurid and sensational nature of some of the newspaper coverage:

‘”I do not think it ought to be allowed in England for anyone to give such a slanderous report,” she said. “He was a fine English boy, living such a clean life.”‘ (Coventry Evening Telegraph, 3 Oct 1934, p. 1).

A sense of the tone of some of the articles can be judged from the headlines:

-

- ‘Collapsed in car. Mystery of young man found dying’ (Daily Mail, 3 Oct);

- ‘Motorist’s mystery death. Coroner orders analysis of organs to be made. Young farmer found dying in car.’ (Reading Standard, 5 Oct);

- ‘Dying man in car. Analysis reveals arsenic. Letter from a girl’ (The Daily Telegraph, 12 Oct);

- ‘Suicide verdict on farm manager. Girl and courtship she wished to end. Dying in car’ (Gloucestershire Echo, 13 Oct);

- ‘Unrequited love tragedy. Suicide of young farm manager. Girl and new attachment. Farewell letter torn up unread.’ (The Sunday Times, 14 Oct);

- ‘Arsenic in stomach. Young farm manager’s suicide. Phone “Goodbye” to girl’ (Shields Daily Gazette, 15 Oct).

I combed the University’s annual reports for the years 1928 to 1935 looking for mentions of Stanley Phalp but could find nothing about him, not even his examination results. There is, however, an obituary in this issue of the Old Students’ Magazine:

The text is a welcome contrast to the press accounts, with no mention of suicide, and is worth quoting in full:

‘MR. STANLEY PHALP died on September 29, 1934. Old St. Andrew’s students will remember his coming to the Hall in his school holidays. He was in the Faculty of Agriculture from 1928 to 1932, and was a member of St. David’s Hall. He was a keen Rugby player and rowed in the Eight of 1931 and 1932, gaining his colours in the former year. At Pondwood Farm, Billingsbear, Wokingham, which Miss Bolam took for him in 1933, he made a reputation in the short time for his intelligent, keen and painstaking methods.’

Thanks to:

Dr Rhianedd Smith (University Museums and Special Collections Services) for passing on material about Mary Bolam from the British Newspaper Archive and for retrieving census data.

Penny Kemp for permission to reproduce the sketch of 30a Northcourt Avenue.

Sources

Childs, W. M. (1927). Miss Bolam. Tamesis, Vol. XXV. Summer Term, No. 10, pp. 209-10.

Holt, J. C. (1977). The University of Reading: the first fifty years. Reading: University of Reading Press.

Kemp, P. (1996). Northcourt Avenue: its history & people. Reading: Northcourt Avenue Residents’ Association.

University of Reading. Old Students’ Association (1935). Mr. Stanley Phalp. Old Students’ Magazine, 21, p. 64.

Newspaper Articles

Arsenic in stomach. (1934, October 15). Shields Daily Gazette, p.6.

Broken romance. (1934, October 19). Western Gazette, p. 10.

Collapsed in car. (1934, October 3). Daily Mail, p. 19.

Deaths. (1934, October 6). The Times, p. 1.

Death of Miss Mary Bolam. (1949, December 9). Northampton Mercury, p. 5.

Dying man in car. (1934, October 12). The Daily Telegraph, p. 12.

Farm manager’s death (1934, October 13). Coventry Evening Telegraph, p. 1.

Found dying in car. (1934, October 3). Hartlepool Daily Mail, p. 2.

Man’s arsenic death. (1934, October 12). Daily Mail, p. 13.

Miss Bolam. (1944, October 6). Reading Standard, p. 5.

Miss Bolam and Governing Council. (1929, August 28). Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette, p. 7.

Miss Bolam’s birthday. (1944, October 13). Reading Standard, p. 5.

Motorist’s mystery death. (1934, October 5). Reading Standard, p. 11.

Northampton will. (1950, March 24). Northampton Chronicle and Echo, p.8.

Reading College. (1900, September 22). Berkshire Chronicle, p. 8.

Suicide verdict on farm manager. (1934, October 13). Gloucestershire Echo, p. 1.

The death of a farm manager. (1934, October 15). The Times, p. 8.

University news. Oxford, July 22. (1896, 25 July). York Herald, p. 6.

University of Reading: Presentation to the first Warden of St. Andrew’s Hall. (1927, December 10). Reading Standard, p. 10.

Unrequited love tragedy. (1934, October 14). The Sunday Times, p. 30.

Young man’s suicide in car. (1934, October 15). The Daily Telegraph, p. 9.