Kathleen Hale, OBE (1898-2000) was an artist and children’s author best known for her stories about ‘Orlando, the Marmalade Cat’ about whom she wrote and illustrated nearly 20 episodes. She created Orlando thanks to a shortage of suitable literature to read to her four-year-old son; she was so tired of bedtimes filled with Beatrix Potter and Babar the Elephant that Orlando was created as a substitute. According to her obituary in The Guardian, Hale despised the style and values in Enid Blyton’s books, calling her ‘the Pied Blyter’. She would never have inflicted them on her own children!

School in Manchester

Hale was born in Scotland but brought up in Manchester where she attended the Manchester High School for Girls. She was a rebellious teenager, described by her headmistress, Miss Sara Burstall, as ‘uneducable and the naughtiest child she had ever had to deal with’ (Hale, 1994, p. 26) (see Women and Higher Education for the link between Sara Burstall and University College, Reading).

In spite of spending most of ‘nine years at the school sitting in the corridor in disgrace’, Hale’s artistic talent was nurtured by a new art teacher, the progressive Miss Ritchie. As Matriculation approached it was clearly pointless for Hale to sit the examination. Instead, Miss Ritchie sent samples of her drawings to University College, Reading. The outcome was a two-year scholarship – two of these were being offered in Fine Art during this period. Her scholarship is recorded in the College’s annual reports in 1916 and 1917.

Hale was still too young to take up the award, however, and had to spend an extra year at school. Miss Burstall had the sense to let her study what she liked and what she was good at: Art, English Literature and French. She was also allowed to attend life-drawing classes at the Manchester School of Art.

University College, Reading-first impressions

In 1915 Hale enrolled in the Department of the Fine Arts led by Allen W. Seaby. Her reaction on arriving at the College is reminiscent of Elspeth Huxley’s disillusionment. Unlike Huxley, she didn’t compare the Great Hall to an outsize garden shed, but she did express her disappointment:

‘From what I had heard of the dreaming spires of Oxford and the backs of Cambridge, I imagined ancient stone buildings drenched in history and drama. I arrived in an almost incandescent ecstasy of anticipation, only to be deflated by the tall, dark-red, Victorian edifice at which I had to announce myself. Nor were my spirits lifted by the rest of the college, which consisted of one-storey departments catering for various branches of learning, linked by ‘cloisters’ paved with cement and with tiled roofs supported by prosaic wooden posts instead of the traditional stone pillars.’ (Hale, 1994, p. 43)

No doubt the dark-red, Victorian edifice was ‘The Old red Building’ that faced London Road and housed the College adiministration.

The Fine Arts Department was no better – it was small and cramped; life models weren’t available (apart from a ‘depressed’ owl in a cage); history of art lectures reminded her of school; the war had left a shortage of staff and students and there was nobody qualified to teach oil painting. There were only five other students, one of whom soon disappeared. It was a sad contrast to the lively, slightly bohemian atmosphere of the Manchester School of Art.

Nevertheless, she settled into college life and enjoyed the courses she attended, including agriculture for which she had to borrow a cap and gown. Eventually, she was to become a close friend of Allen Seaby whom she described as ‘a wry old man, brittle with rheumatism, but as cheerful and alert as a bird’. In her autobiography she explains how he taught her to produce traditional Japanese woodcuts.

A close shave!

There was, however, one blot on the horizon – at the beginning of her autobiography, Hale explains that twice in her life she had narrowly avoided expulsion for immorality or indecency. The first, at the age of twelve, was for drawing bare-breasted mermaids in the margin of her religious textbook. The second, at Reading, was for having her hair ‘cut in short bob with a fringe’ (Hale, 1994, p. 7) for which she was summoned before a special meeting of the College governors. Being hard up at the time, she had sold the hair for £5.

This is how she told the story to Sue Lawley on Desert Island Discs in 1994:

KH: ‘It was so long and so heavy [that] when I did it up with hundreds of hairpins it would slowly uncoil and slide down the back of my neck with [the] hairpins too. So it was quite long.’

Sue Lawley: ‘But it was quite a racy thing to do, really, to cut your hair off short.’

KH: ‘Yes, yes. I wasn’t the first, but at the Reading University [sic] I was, and they said I’d have to go down. They couldn’t accept [it]. I said, well, I haven’t cut off my morals with my hair and then there was a long silence and I found I was still enrolled as a student.’

The matter was never mentioned again and she continued with cropped hair for the rest of her life.

College Life

Otherwise, apart from some anxiety about her body shape, all was well. She had a single room in St Andrew’s Hall, took advantage of the sports facilities, playing tennis, skating in the winter, joining the rowing club and learning to punt – a sharp contrast to her hatred of sport at school.

She was particularly impressed by Dr Hugh Percy Allen, Director of the Music Department and a charismatic teacher. She joined his choir but didn’t actually dare to sing; she mimed the words in silence. When Dr Allen became aware that she had no voice he allowed her to remain as a reward for her enthusiasm.

St Andrew’s Hall was ruled by the eagle-eyed warden, Miss Bolam, who keenly enforced the rule that students should attend a place of worship on Sunday mornings. Hale found a solution to this:

‘… when it was time for church and I had to walk past Miss Bolam sitting at her window, I ostentatiously carried a volume much the same size and colour as a hymn-book; then I would spend the morning peacefully reading in a field, and mingle craftily with the churchgoers on their return. But the lady sensed my deception and blandly questioned me on the content of the sermon and the choice of hymns. I tried to placate her, assuring her that I spent Sunday mornings in the contemplation of God’s presence in nature. She was better able to understand my spending some of my Sunday mornings at Quaker meetings…’ (Hale, 1994, p. 48)

Hale’s scholarship ended in 1917 when she was 19. There is surprisingly little information available about her examination results, just a single mention in 1916 of passing History of Painting, part of the Diploma in Fine Arts. There seem to be two reasons for this lack of documentation. First, Fine Arts students were exempt from some of the assessment that other diploma students underwent. Second, even though diploma courses usually lasted two years, Fine Arts (and Music) required three. So Hale was a year short of completion.

The Governors of the College offered to extend the scholarship for a year in acknowledgement of her ‘dedication and talent’ but Hale was anxious to see what ‘Life’ was like:

‘I sold my excellent bicycle for the price of a single ticket to London, and set out with only a few shillings in my pocket, my pince-nez delicately chained to one ear and no qualifications whatsoever for earning a living.’ (Hale, 1994, p. 51)

Return Visit to St Andrew’s Hall

In 1978 the University Bulletin recorded that an eighty-year-old ‘distinguished visitor’ had returned to St Andrew’s Hall. Kathleen Hale, now Mrs Douglas McClean, was photographed on the stairs in the entrance hall which now (in 2026) is the exhibition area for the MERL and Special Collections. It was here that the young student had heard classical music for the first time, sitting on the stairs and listening to concerts given by the music students. She claimed she had never seen a piano before, let alone a cello, violin or flute.

Hale was welcomed by Dr Elizabeth Edwards, Warden of St Andrew’s, and shared anecdotes such as the time when members of the Royal Flying Corps, then occupying Wantage Hall because of the war, invited the women of St Andrew’s to a dance. The College authorities refused permission, but Miss Bolam subsequently agreed to invite the airman to a dance in her own hall. There were enthusiastic preparations by the women, but the men took their revenge by not turning up.

Postscript

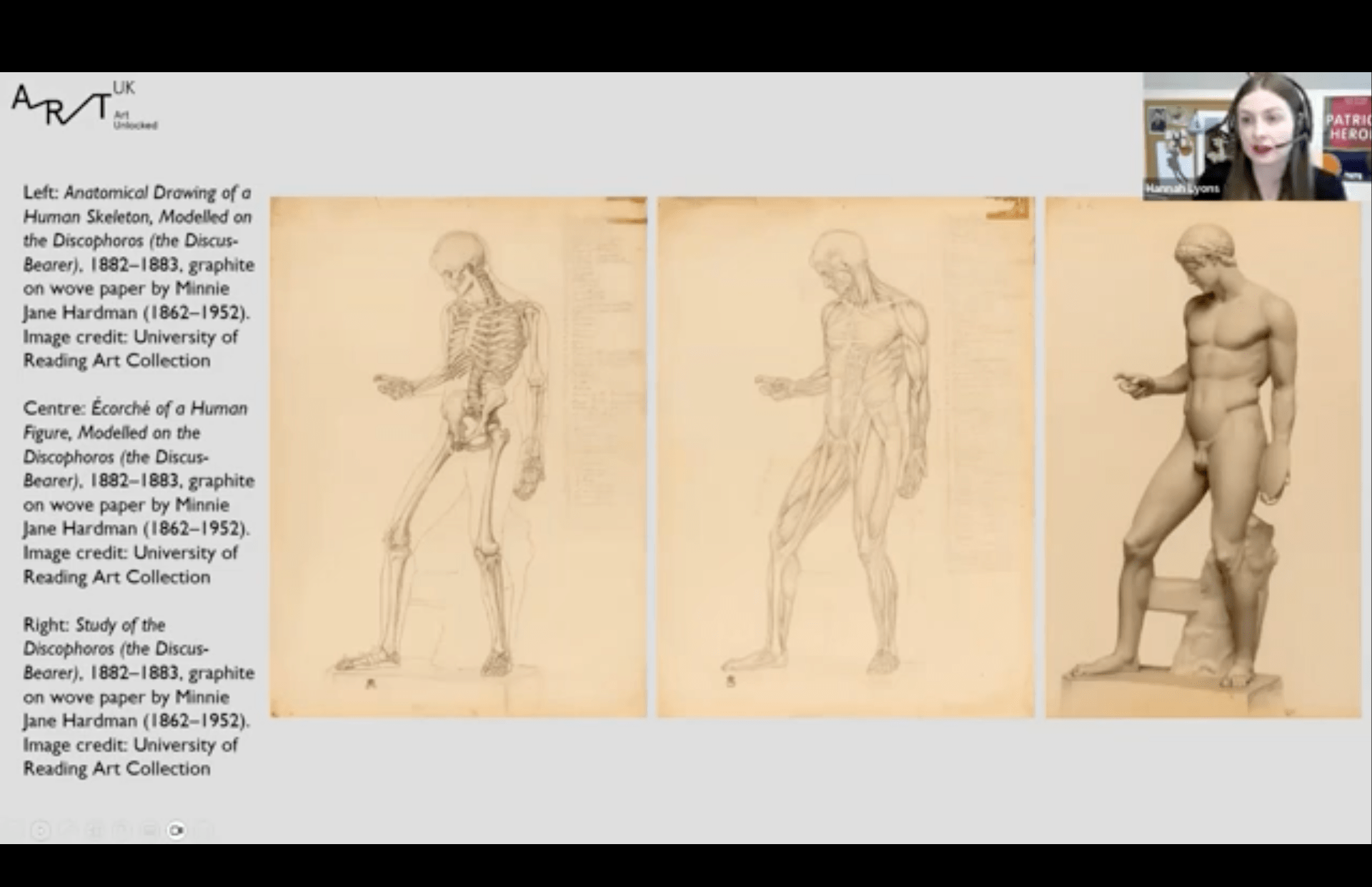

The University of Reading’s Art Collection holds six portraits by Kathleen Hale, all completed in 1920, well before the first Orlando story. They include the large pencil drawing below. The other five, together with information about Hale’s early struggle for recognition as an artist, can be viewed on the Art Collections website. There is much more to Kathleen Hale than Orlando!

Thanks to:

Michele Drisse (Reading Room Supervisor, Museums & Collections); Dr Hannah Lyons (Curator of University Art Collections) and Sharon Maxwell (Archivist, Cataloguing & Projects) for their help with this post.

Sources

Desert Island Discs, 30th October 1994. Kathleen Hale – BBC Radio 4.

Hale, K. (1994). A slender reputation. London: Frederick Warne.

MacCarthy, F. (2000, January28). Obituary: Kathleen Hale. The Guardian.

Parkin, M. (Ed.) (2001). Memorial Exhibition: Kathleen Hale 1898-2000. London: Michael Parkin Fine Art.

University College, Reading. Annual Report of the Academic Board, 1915-16 & 1916-17.

University College, Reading. Calendar, 1915-16 & 1916-17.

University of Reading Bulletin, May 1978, No. 102.

University of Reading. Calendar, 1977-78.