According to The Economist ‘the Lionesses are national heroines’ (19 August 2023). When they roared at the Euros in 2022 and again at the World Cup this summer, we were repeatedly reminded how the Football Association had banned women from their pitches in spite (or perhaps because of) the fact that women’s football was flourishing during the years following World War I. The FA’s justification was that football was ‘quite unsuitable for females’.

Edith Morley and Sport at Reading

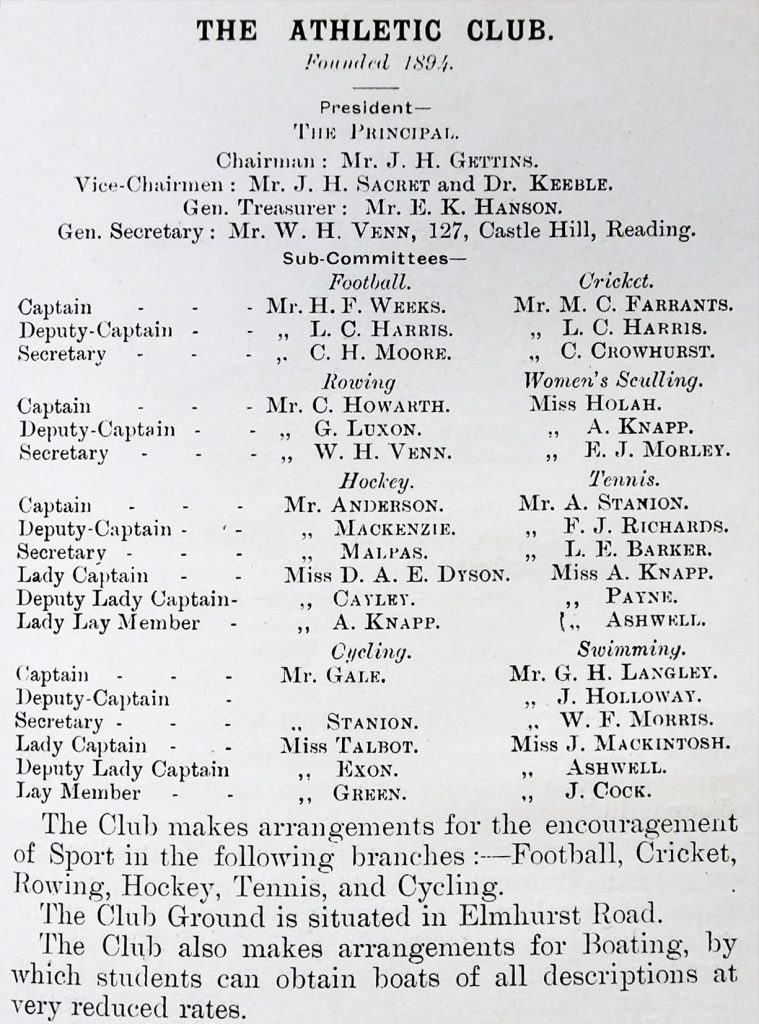

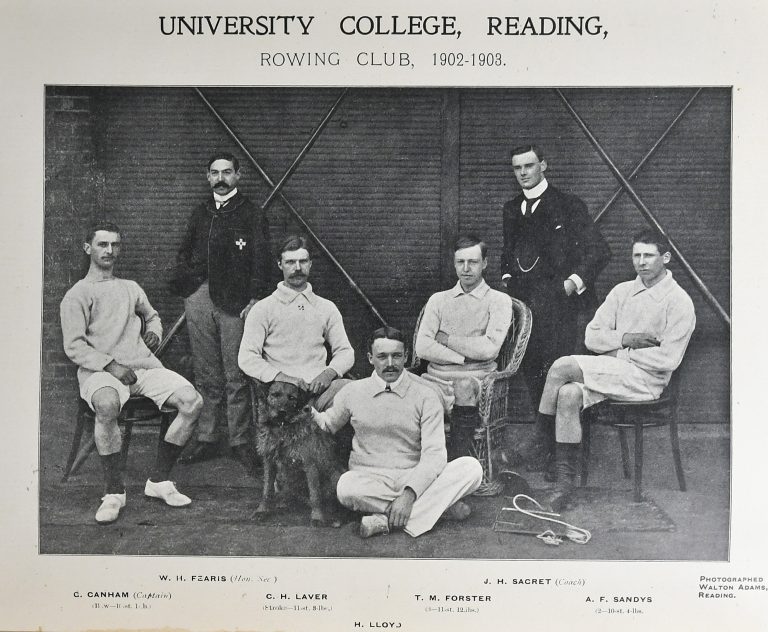

Reading University’s archives contain similar views about competitive rowing, even though in 1894 Women’s Sculling was the first sports club to be established at the College. Edith Morley was its Secretary from 1904 to 1907. It was only natural therefore that in 1917 she would be co-opted onto a committee that investigated whether boat racing was an appropriate activity for women. A letter to the Principal from Sir Isambard Owen, Vice-Chancellor of Bristol University, contained the following opinion:

‘Shall I be out of place in adding my opinion, as a physician, that rowing in races is not a suitable form of exercise for young girls?’ (Special Collections, UHC AA-SA 8).

In addition to sculling, the young Edith Morley’s sporting interests had included hockey and cycling. She had been given a bicycle for her 21st birthday but her father was wary of letting her ride it:

‘A few women had begun to ride a year or so before when safety bicycles first came into use, but in 1896 bicycling was still so unusual a proceeding for girls, that my father took counsel with various medical friends to find out whether there was any likelihood of my injuring myself permanently if he allowed me to accept the preferred gift.’ (Morley, 2016, p. 65).

The description of her cycling escapades that follows is further evidence of Morley’s spirit of adventure and sense of humour. She is, however, also making a serious point:

‘The acceptance of that bicycle marks an epoch in my life for it brought me, as it brought many other girls, hitherto undreamed-of freedom and emancipation. The bicycle meant a speedy end of chaperonage, the power to go on long expeditions on one’s own, the means of locomotion and enterprise previously denied women.’ (Morley, 2016, p. 65).

Hockey

As a hockey player, Morley claimed to be enthusiastic rather than talented, but she did have the distinction in 1901 of being a member of the first English women’s team to play in Holland. These were not official internationals, but Morley’s team won all their matches, one of which was attended by Queen Wilhelmina.

Earlier, Morley had joined the King’s College Hockey Club, one of the earliest London clubs for women. They had to play in skirts that hung exactly six inches above the ground, checked with a tape measure by the team captain. As skirts of this length were considered to be ‘indecently short’, players never wore them other than on the hockey pitch. Even so, the sight of a woman carrying a hockey stick in public brought forth cries of ‘new woman’ from bus conductors or passers-by.

Worse mockery can be found in Reading’s College Magazine in its second issue in 1901:

‘The Athletic Club Ground presents a sight every Thursday afternoon which is by turns sad and amusing. A seemingly numberless host of girls are closely packed together on a very small section of the hockey ground. All are armed with hockey sticks which they use unceasingly to belabour any large or small object within their reach. At long intervals a ball appears, which, as soon as a fair player discovers, she promptly sits down upon it. This is an extremely healthy method of taking exercise, and one which we can sincerely recommend to all our lady readers.’ (College Notes, Reading College Magazine, 1901, Vol. II, pp. 11-12).

In the next issue, a letter to the Editor retaliated with comparable sarcasm:

‘Dear Editor, – It is a pity that those who don’t take a prominent part in Athletics should make fun of those who do. They probably, however, make up for it by longsightedness, as this is essential for a person who sees what is going on at the Athletic Ground while “stewing” in the College Library, instead of taking healthy exercise; or perhaps they borrowed Kosmos Telescope. A Hockey Player.’ (Reading College Magazine, 1901, Vol. III, p. 32).

We need to remember that in 1901 Reading College, as it was known then, was still based in Valpy Street next to the Town Hall. Kosmos was the College Science Club – perhaps the ‘Hockey Player’ suspected the identity of the original writer.

The first mention of women’s hockey in the College calendars is in the issue for 1899-1900 where a Miss Gaynor was the ‘Lady Captain’. As for photographs, the earliest I have found is of the St Andrew’s team of 1906-7, mentioned in a previous post; and the Special Collections also hold a postcard of the College Team taken the following year:

The reverse shows eight names, handwritten and not always easy to decipher:

Some information about the women named can be found in examination results, in the College Annual Reports and copies of the Gazette, and in the Calendars’ lists of sports club committees:

-

- ‘Nell’ Plumley was probably Eleanor L. Plumley who passed the final examination for the Diploma in Letters in 1909.

- ‘Kitty’ Green was Lady Captain of Hockey, 1908-9 and 1909-10. I assume she was Kate Green who was awarded the BA of the University of London (Pass, Division II) in 1909.

- Nora A. Curtis studied science receiving her BSc Pass Degree, Division II, in 1910.

- Winfred M. Spain studied Arts and Education (distinction for years 1 and 2), and was awarded 1st Class Honours in Modern European History in the University of London Examinations of 1909.

- Gertrude S. Black was Lady Captain, 1907-8. If I have identified her correctly, she studied Horticulture, obtaining Class I in the Royal Horticultural Society Examinations in 1908 and the Associateship in Horticulture in 1909.

- Elsie S. Metcalf was Lady Secretary, 1908-9. She won the College Prize for University Students in the Faculty of Letters and the University College Scholarship for Singing in 1909.

- Maude G. Scott obtained the Diploma in Letters in the 1909 final examinations with a Distinction in Philosophy; in the same year she received the ‘Recognition of Teachers for Elementary Schools’.

- Edith Elliott was Deputy Ladies Captain, 1908-9. She passed the Year 1 Associate Examination in Philosophy and History in 1908.

The contrast between the image above and those of more recent students couldn’t be more conspicuous:

Jolly Hockey Sticks

Nevertheless, for a long time a combination of gender and social class connotations persisted, encapsulated in the phrase ‘jolly hockey stick(s)’. The Oxford English Dictionary’s first citation of this is from the character actress and comedienne Beryl Reid who used it in her comic portrayal of a schoolgirl in 1953.

The full OED entry attests to three closely related meanings: as an interjection; as an adjective; and as a noun. The definition of the first of these reads as follows:

‘Used in representations or imitations of upper or upper-middle-class speech associated with a type of English public schoolgirl, esp. to express (mock) boisterous enthusiasm, excitement, exuberance, etc.’

Descriptions like this seem amateurishly remote from the 21st Century. There may be hockey sticks here, but there’s certainly nothing jolly about them!

Post Script

With support from The Friends of the University, ‘A History of Sport at University of Reading’ was published in 2021. This was a collaborative project involving Iain Akhurst, Director of Sport from 2004 to 2019, Dr Margaret Houlbrooke, Professor Cedric Brown, and Chris Lewis (Department of Typography).

THANKS

To Sharon Maxwell, Archivist at the Museum of English Rural Life/Special Collections Service, for finding the original references to hockey in the College Magazine.

Sources

Anonymous contribution to College Notes. Reading College Magazine, 1901, Vol. II, pp. 11-12.

Letter to the Editor. Reading College Magazine, 1901, Vol. III, p. 32.

Lionesses of the future. A game-changer for domestic football. (2023, August 19). The Economist, p. 26.

Morley, E. J. (2016). Before and after: reminiscences of a working life (original text of 1944 edited by Barbara Morris). Reading: Two Rivers Press.

Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “jolly hockey sticks, int., adj., & n., Forms”, July 2023. <https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/8243969470>

Reading College. Calendar, 1899-1900.

University College, Reading, Annual Report, 1908-09.

University College, Reading, Calendar, 1907-08 to 1909-10.

University College, Reading, Official Gazette, No. 51. Vol. V. July 3, 1907.

University College, Reading, Official Gazette, No. 52. Vol. V. November 25, 1907.

University College, Reading, Official Gazette, No. 55. Vol. VI. December 15, 1908.

University College, Reading, Official Gazette, No. 56. Vol. VII. October 25, 1909.

University of Reading (2021). A history of sport at University of Reading 1892-2018.

University of Reading Special Collections, Uncatalogued papers including correspondence about Boat Racing, Reference UHC AA-SA 8.

University of Reading Special Collections, MS 5305: University History, Photographs – Groups Box 1.