The appendix to J. C. Holt’s history of Reading University helpfully names all its officers, professors and librarians who were in post between 1926 and 1976 (pp. 331 ff.).

The first four Vice-Chancellors are listed like this:

-

- 1926-9 W. M. Childs

- 1929-46 Sir Franklin Sibly

- 1946-50 Sir Frank Stenton

- 1950-63 Sir John Wolfenden

Ever since I first came across Holt’s book almost a decade ago, I wondered why William Macbride Childs, Reading’s first Vice-Chancellor, was never knighted.

Out of Reading’s ten Vice-Chancellors, five have received knighthoods, though not always solely for their academic leadership, and David Bell was already ‘Sir David’ on his appointment.

Nevertheless, Childs would seem to have been a prime candidate. After all, it was largely thanks to him that a relatively obscure College developed sufficiently to receive the Royal Charter (even Edith Morley had never heard of the College before she was invited for interview in 1901).

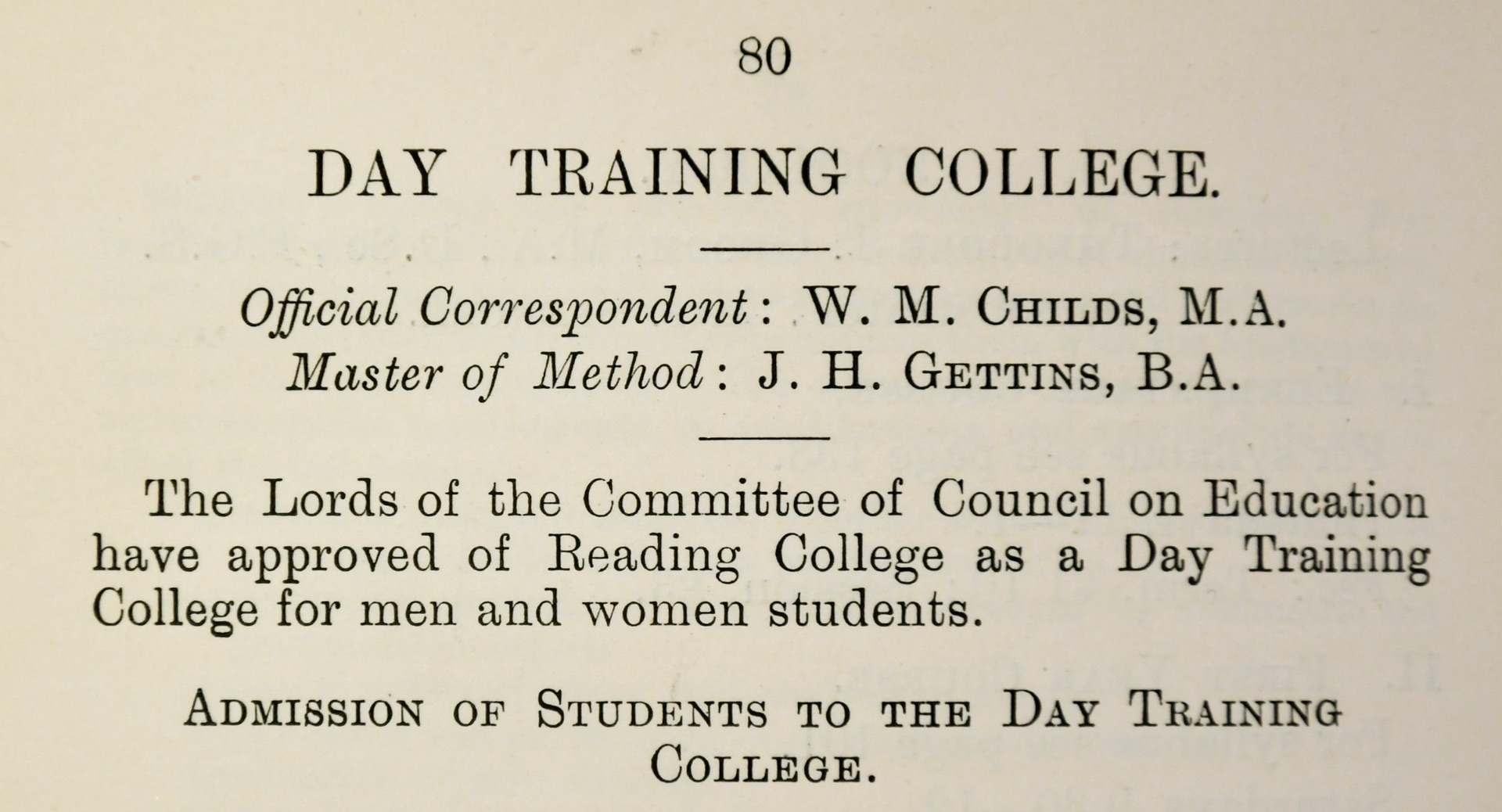

Childs’s relatively short tenure as V-C was the culmination of a much longer association with the College. It began inauspiciously in 1893 with a part-time position teaching history to pupil teachers, some coaching and giving University Extension lectures. In a parallel with Morley’s experience 8 years later he explains that;

‘I knew nothing about this new College, nothing about Reading ….’ (W. M. Childs, 1933, p. 1).

By 1903, however, Childs had become the Principal of what had recently become University College, Reading, and he soon developed a vision for achieving full university status. Here’s how Professor Holt recounts his achievement:

‘From the moment in 1906 when he first announced it, he pursued the objective of university status with a methodical and relentless intent. He was personally responsible for some of the most characteristic features of the University College: the emphasis on residence and the importance of agriculture. He was the inspiration behind the movement for the Charter.’ (Holt, 1977, p. 28).

Not that Holt was blind to Childs’s faults and errors; he documents these in some detail and concludes:

‘He was a man to found a university. He was not equally a man to develop one once founded’ (Holt, 1977, p. 28).

Following Childs’s retirement in 1929, the issue of a knighthood was a matter of concern for family, friends and fellow academics. Writing of the accolades his father had received, Hubert Childs wondered:

‘…. why was it that in all the eagerness to pay my father honour and to mark his achievement by words and action worthy of it, there was, seemingly, no recognition by the State of what he had done and stood for? The omission caused him little personal concern, for he attached no great importance to such things; but it perplexed his friends who expected a knighthood to be conferred upon him, both in honour of himself and the new University.’ (H. Childs, 1976, pp. 145-6).

One possibility was that the political instability following the General Election of 1929 and a change of Government were the explanation, but this idea was rejected by Hubert Childs.

More likely, in his opinion, was that, on separate occasions, his father refused to accept both the Freedom of the Borough of Reading and a knighthood unless Alfred Palmer, his friend and benefactor received the same honour.

As Hubert Childs concluded:

‘Those who attempt to apply conditions to the acceptance of honours inevitably run the risk of falling foul of unrelated and unthought-of considerations, and this may be what happened in this case.’ (H. Childs, 1976, p. 147).

Sources

Childs, H. (1976). W. M. Childs: an account of his life and work. Published by the author.

Childs, W. M. (1933). Making a university: an account of the university movement at Reading. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd.

Holt, J. C. (1977). The University of Reading: the first fifty years. Reading: University of Reading Press.

Morley, E. J. (2016). Before and after: reminiscences of a working life (original text of 1944 edited by Barbara Morris). Reading: Two Rivers Press.

The Magazine of University College Reading, 1904, Autumn Term, Vol IV, No. 1.

University of Reading Special Collections: University History MS 5305 Photographs – Portraits Boxes 1 & 2.

Thanks

To Ian Burn for supplying the correct image of Professor Holt.