Building L16 at London Road houses Campus Reception and the students’ Support Centre; it is also the administrative hub of the Institute of Education.

When I joined the School of Education at London Road in September 1987, my office was on the first floor of L16. It nestled between the display area and the lecture room of the Reading and Language Information Centre (RALIC) run by Betty Root MBE.

On the ground floor was Modern Languages led by Gordon Shute and Art Education with Fraser Smith and his colleagues James Hall and Richard Hickman. Gordon Shute also ran the Short Courses Office in what is now Campus Reception.

My office was large enough to accommodate a seminar group of 12 students, quite a luxury for a new lecturer. None of the offices had a computer until we received a portable Amstrad in the summer of 1988. There was no network; everything was transferred on 3.5″ floppy disks.

Originally, I thought my old office was today’s Room 110, but having compared the brickwork and partition walls of Rooms 108, 110 and 112, I now believe it to have been 108, and that the original Reading Centre lecture room has been divided to form 110 and 112. Whatever the case, present staff in these three offices no longer have the luxury of ‘a room of one’s own’ – each is shared by two or three staff.

In 1989 the University merged with Bulmershe College of Higher Education and the Faculty of Education and Community Studies was formed. At some stage following Education’s departure from London Road to Bulmershe Court these rooms on the first floor were occupied by the Centre for British Teachers, by coincidence my previous employer.

‘The Tech Block’

Two people who remember lecturing in L16 even before it housed the School of Education are the microbiologists Dr John Grainger and Dr Gillian Roberts (now Dr Gillian Grainger). According to John, it was known as ‘The Tech Block’ as a result of its previous history as the location for Commerce and Technical Subjects:

‘By 1957 when I came to Reading the term ‘Tech Block’ for L16 seemed to have been part of tradition in the London Road vocabulary since whenever. I guess it emerged when ‘Commerce’ was no longer part of the activities in L16 and ‘Tech’ was less of a mouthful in conversation than ‘Technical Subjects’ or similar.’ (Dr John Grainger, August 2024)

John Grainger, who later became head of Microbiology before it was absorbed into the School of Animal and Microbial Sciences, recalled that during his time in L16 academic staff were still obliged to wear gowns during their lectures. By about 1970, however, when his wife Gill was lecturing there, this requirement had ceased.

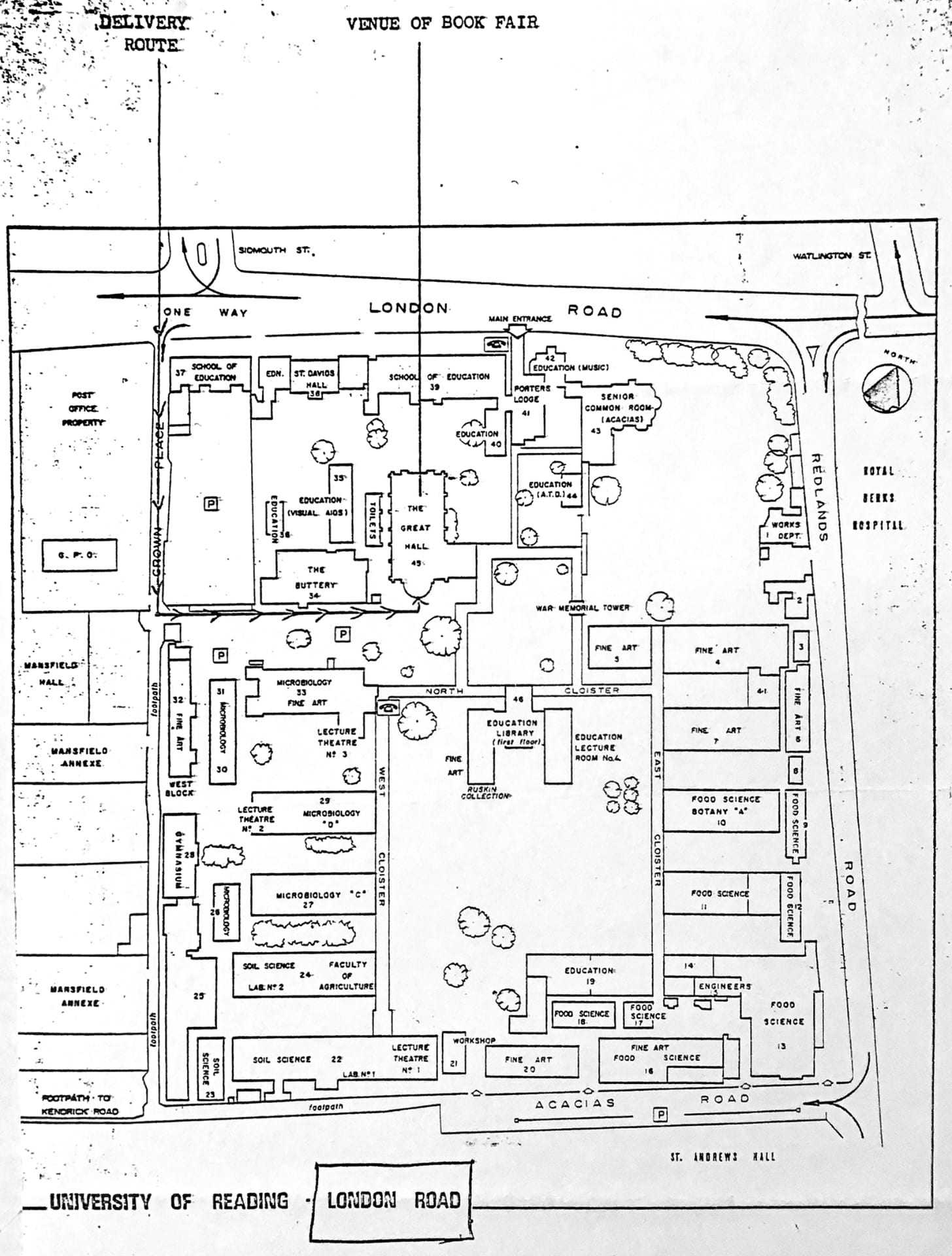

It was only this year that I realised the logic behind the numbering of the buildings at London Road. The earliest map I have found that shows the numbers is from 1977 (see post of 16 January 2024). The sequence begins in the north-east corner of the campus and moves in a clockwise direction round the site. L16, therefore, was originally the 16th building to the south on the east side. Thanks to so many buildings being demolished or knocked into one, however, the sequence is less transparent today.

Origins

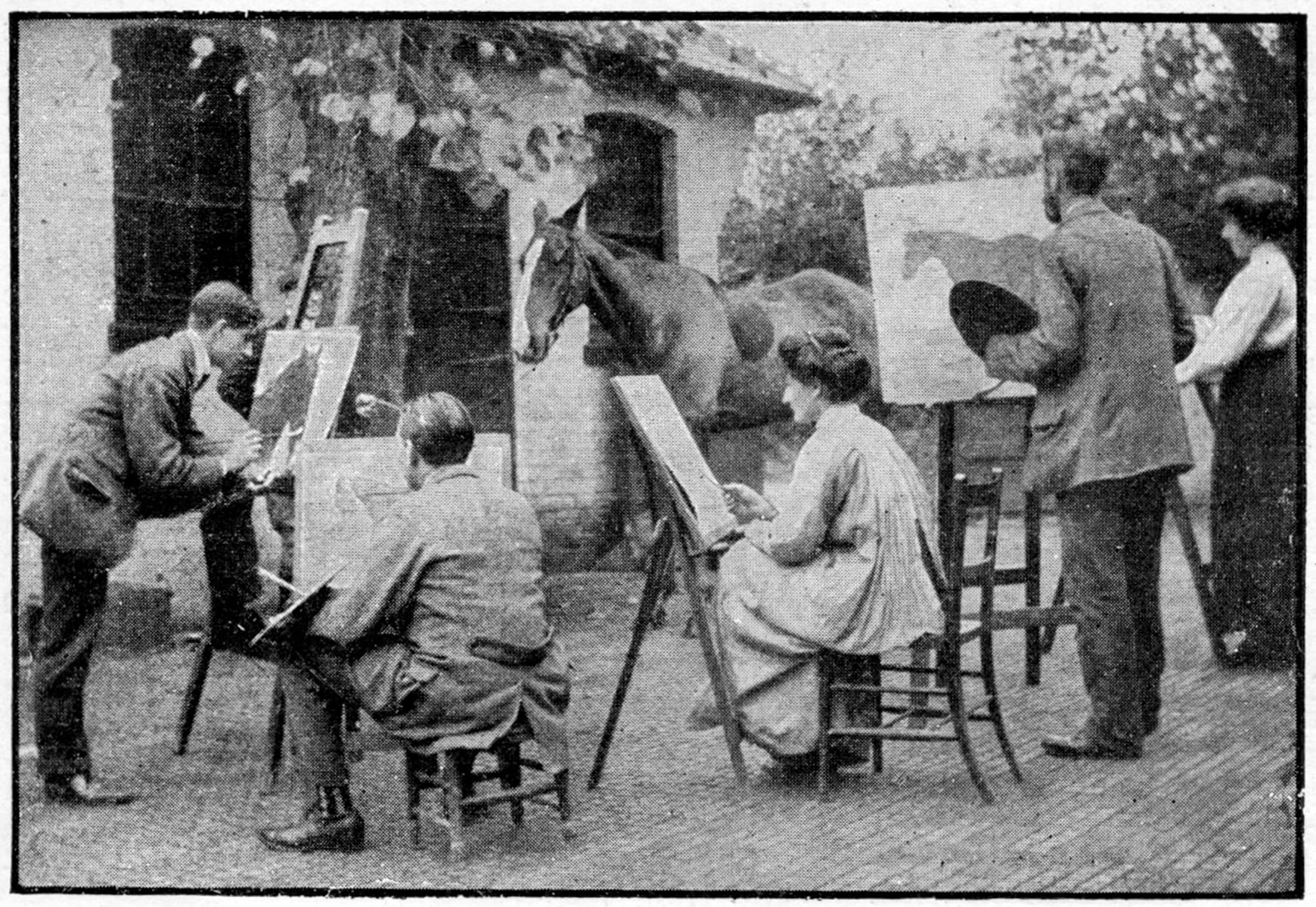

In 1904 Alfred Palmer gifted the University College the grounds on which the buildings along the east cloister were soon to be constructed. A map of that year published in the College’s Official Gazette describes the southeastern section where L16 was to be situated as the Palmer Family’s paddock.

Before Palmer’s gift, the area had been rented by the College and was variously referred to on site plans as ‘The College Garden (for Horticultural Teaching and Practice’ (Calendar, 1902-3) and ‘Horticultural Ground’ (Childs, 1933).

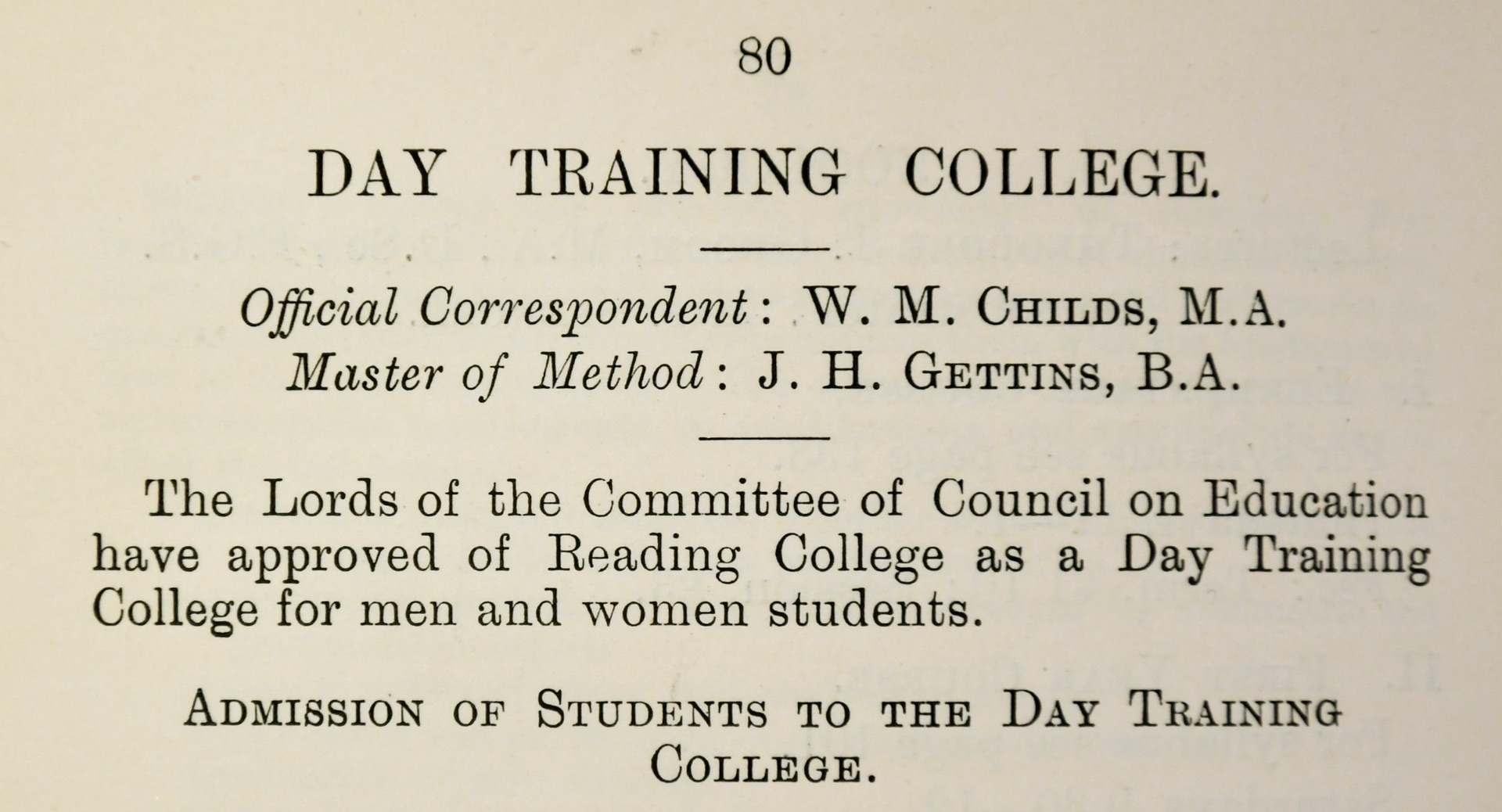

The original architects’ plan produced by W. Ravenscroft and C. S. Smith and presented to Dr Childs, the College Principal in 1904, was reproduced in the Students’ Handbook in 1907. L16 is the building on the far left and, uniquely, is unlabelled.

Following the site’s construction, the first map on which L16 is discernible is a ‘Sketch Plan of Reading Shewing University College’ published in the College Calendar in 1906. A close-up of the campus section can be seen here:

Occupants of the Building

As noted above, L16 was unlabelled on the architects’ plan. However, architects’ notes received by the College in 1907 refer to a Geography building that isn’t to be seen on the original plan. This can only be L16:

‘GEOGRAPHY. This building contains 2400 square feet, and comprises two large rooms for the use of commercial and geographical classes, a large room for typographical teaching, and private rooms for members of staff.

The basement storey adjoins the agricultural building and comprises a large boiler house and coal store. Into this basement all gas, water and electric light supplies are brought. Here the meters are fixed, and thence supplies are taken via the creeping way to the whole of the new buildings on the site.’ (Ravenscroft & Smith, 1906, pp. 7-8).

Note that ‘adjoins’ here does not mean that the buildings were attached, but simply that they were in close proximity to each other, as can be seen on the architects’ plan.

Later campus maps give us further information:

-

-

- A ‘Development Plan’ of 1911 published a year later in the College Review describes the building as the ‘Commerce and Technical Block’;

- A ‘Plan of Buildings on the Main Site’ of 1926 shows the occupants to be ‘Geography Commerce Domestic & Technical Subjects’;

- Two different plans from 1929, both labelled ‘Plan Showing Existing Buildings and Proposed Extensions’ use the label, ‘Commerce and Technical Subjects’ (University Gazette, 1929; Special Collections UHC – PLANS Box 1);

- A ‘Plan of Buildings on the Main Site’ from the early 1930s published in Smith & Bott’s (1992) pictorial history of the University includes the word ‘Domestic’ for the first time: ‘Domestic and Technical Subjects’;

- Holt’s (1977) history of the University includes ‘The development plan for London Road, 1944‘ showing ‘Technical Subjects’; in addition, the word ‘Commerce’ has been crossed out and replaced by ‘Agriculture’;

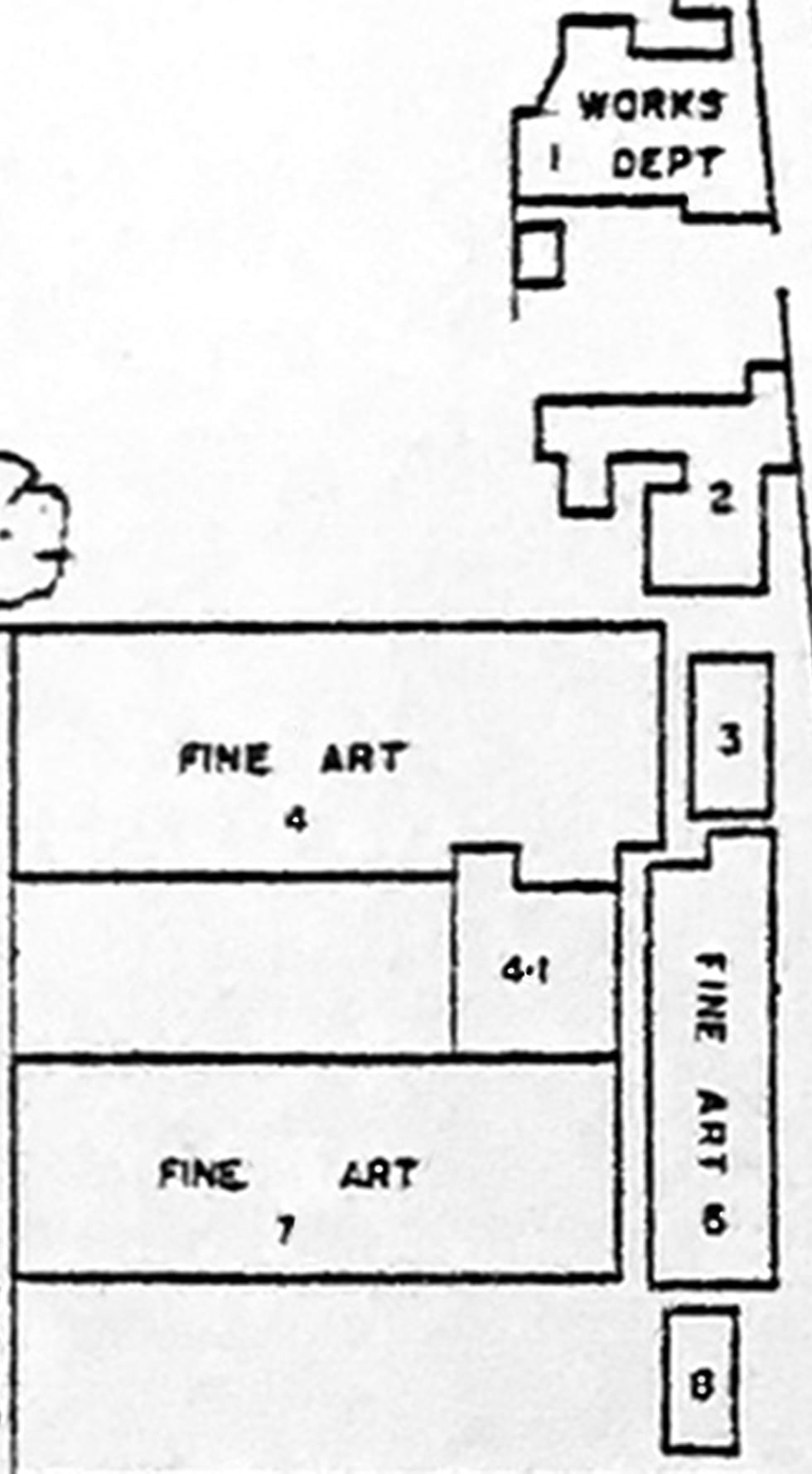

- An undated plan that was in use in 1977 and was found in the Christine Pullein-Thompson Collection, show the building in use for ‘Fine Art’ and ‘Food Science’ – by this time most departments had moved to Whiteknights and London Road was occupied by just five main departments: The School of Education, Fine Art, Food Science, Microbiology and Soil Science.

-

With regard to the frequent references to Commerce, and Technical and Domestic Subjects, these curricular areas have their origin in the evolution of the University from the Extension College of 1892 and its amalgamation with the Local Schools of Art and Science. As Holt (1977) points out, much of the teaching in 1926 when the Royal Charter was granted, was not at a level associated with other, more established universities.

Out of 1,656 students at Reading, only 306 were reading for a degree, less than half the number of evening class students. Because there had been simply nowhere else for non-degree students to go, they and their courses were incorporated lock, stock and barrel into the University.

L16 and the War Effort (1914-18)

In his memoir W. M. Childs reported that:

‘Throughout the war period, the College and those still at work within it busied themselves with many kinds of public service. For example, large quantities of munitions were made, and many hundreds of munitions-workers were trained. We exerted ourselves to stimulate locally the production of food. Our Voluntary Aid Detachment set up a hospital through which passed more than 1300 wounded men ….’ (Childs, 1933, p. 218)

Annual reports of the period mention the Fine Art Department making ‘War Hospital appliances’ in the woodwork shop; Chemistry was making B[eta]-eucaine for the Admiralty, an early substitute for cocaine that was used as a local anaesthetic.

In 1916 it was noted that the training of munitions workers had been moved from the Physics building to larger rooms in the Commerce building (presumably L16) where new lathes, machines and an extra electric motor were installed. By the end of 1916, 157 men and women had been trained. During the course of their instruction they had produced 4,000 shell bases and 200 Maxim crosshead pins.

The Changing Shape of the Building

Today the shape of L16 is an almost perfect rectangle but it wasn’t always so. The image below shows the original plan and later changes to the east-facing wall (bottom right on each plan):

An early undated image in the Special Collections shows some differences from the modern building but these don’t correspond with the above diagrams, and, to date, I have been unable to find the documentation that explain these and subsequent alterations.

The east wall has since lost its lower window, and the chimney has been replaced. A close-up taken in 2024 shows three generations of brickwork suggesting an extension or major reconstruction:

The join can be be seen more clearly on the north and south walls:

Thanks to:

Ian Burn, John and Gillian Grainger and Dennis Wood for their contributions to this post.

Sources

Childs, W. M. (1933). Making a university: an account of the university movement at Reading. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd.

Holt, J. C. (1977). The University of Reading: the first fifty years. Reading: University of Reading Press.

Ravenscroft, W. & Smith C. S. (1906), Notes by the Architects on the New Hall and Buildings. Special Collections, Ref: C Box 1466.

Reading University Gazette. Vol. II. No. 2. March 21, 1929.

Smith, S. & Bott, M. (1992). One hundred years of university education in Reading: a pictorial history. Reading: University of Reading.

The Reading University College Review, Dec 1912, Vol V No. 13.

University College Reading. Calendars, 1902-3, 1906-7.

University College, Reading. Official Gazette. No 34. Vol. III. 22nd February, 1904.

University College, Reading. Reports of the Council, 1914-15, 1915-16, 1916-17.

University College Reading (1907). Students’ handbook. First issue: 1907-8.

University of Reading (1929). Plan Showing Existing Buildings and Proposed Extensions. Special Collections. ref: UHC – PLANS Box 1.

University of Reading Special Collections. Christine Pullein-Thompson Collection, Correspondence with Publishers, Granada: MS 5078/107.