Following Reading College’s recognition as a Day Training College in 1899, it became increasingly evident that, despite construction work, the premises on Valpy Street were inadequate for an institution that had aspirations to become a University College or University. As W. M. Childs put it in ‘Making a University’:

‘The new buildings of 1898 gave relief, but we had hardly become used to them before we began to outgrow them. The prospect was serious. The site would take no more buildings; it could not be enlarged and to put part of the College elsewhere would destroy unity, and was otherwise impracticable. We began to talk of migration and rebuilding, not too hopefully.‘ (p. 38)

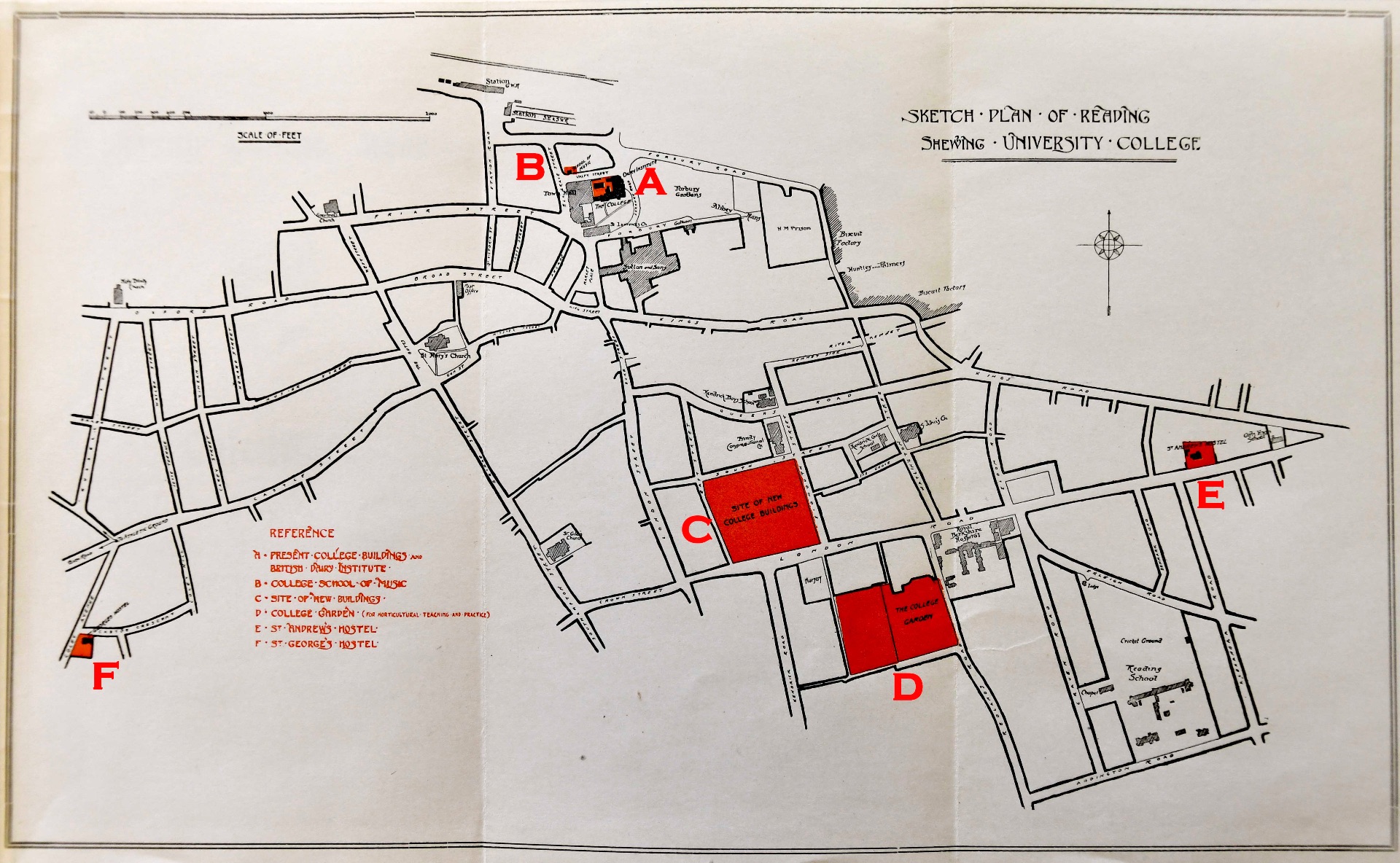

It is well known that the original College was relocated to the present London Road Campus in 1905. I was surprised to discover, therefore, that a sketch plan of Reading dated 1902 showed the present location of Kendrick School as the new site.

The locations marked on the plan are:

-

- A: College Buildings and British Dairy Institute in Valpy Street;

- B: College School of Music;

- C: ‘Site of new College buildings’ (now Kendrick School);

- D: College Garden (rented for Horticultural Teaching and Practice – now part of the University’s London Road Campus);

- E: St Andrew’s Women’s Hostel;

- F: St George’s Women’s Hostel.

The explanation for this anomaly is that in 1901, Reading’s Town Council came up with a proposal that would have solved the College’s problems of space: the College’s premises in Valpy Street would be exchanged for the section of municipal estate shown on the map. The parties came to an agreement the following year and all seemed well until 1903 when lawyers uncovered insurmountable problems relating to the proposal’s legal validity, leasehold rights and possible restrictions on building.

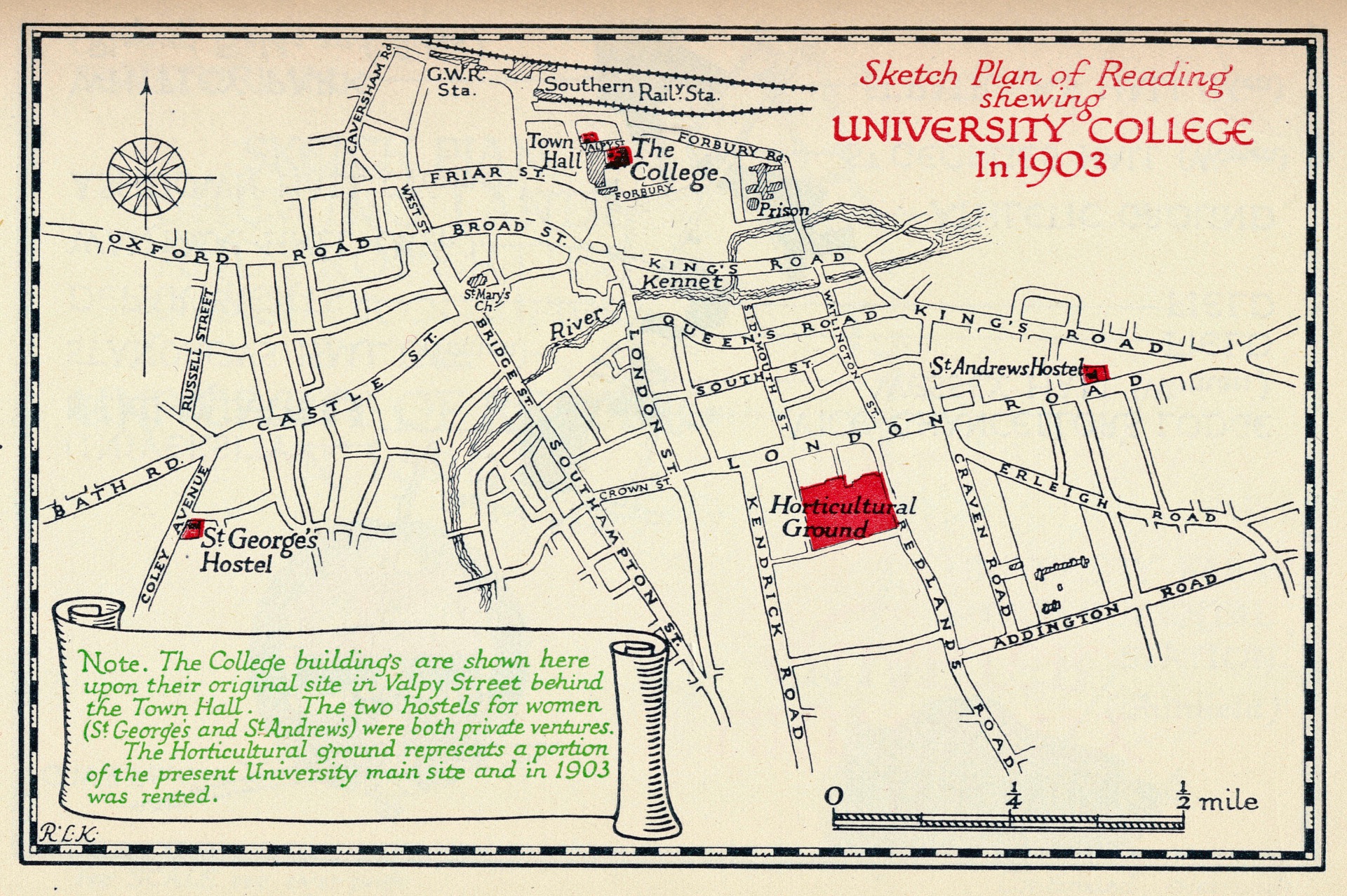

In the College map of 1903, therefore, reference to the ‘Site of new College buildings’ had been removed.

In 1903, W. M. Childs took over from H. J. Mackinder as Principal of what was now University College, Reading. It was Childs who sought a solution by approaching Alfred Palmer, a member of the College Council, about the possibility of taking over land and buildings on London Road that had been the Palmer family home.

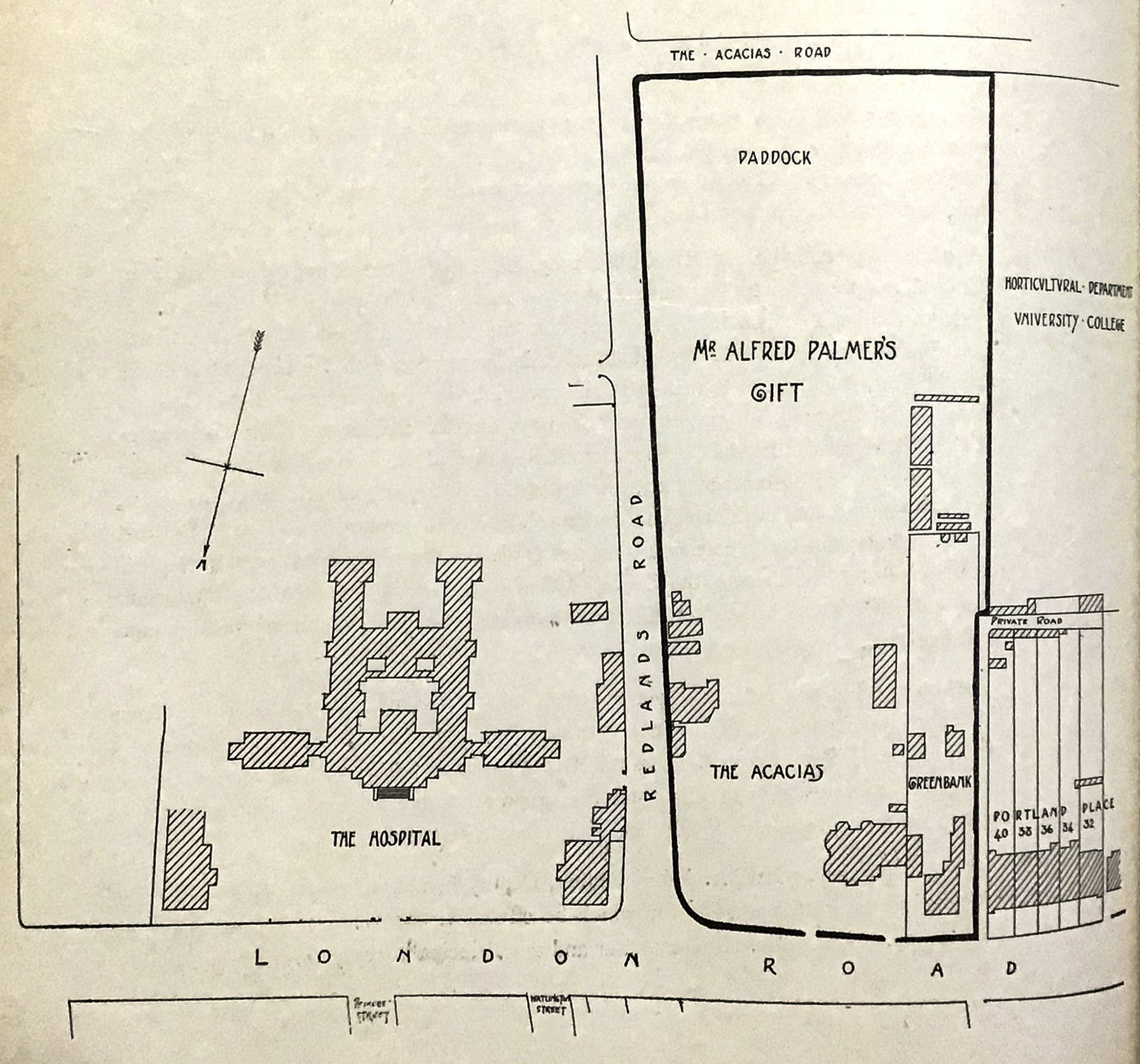

Palmer had recently agreed to donate £6,000 to the College building fund, and an agreement was reached by which this donation was sacrificed in exchange for the transfer of the property to the college. The following is an extract from Palmer’s letter of agreement, written to the Principal from his home in Wokefield Park, Mortimer on January 13th 1904:

‘I am willing to give the College the grounds and buildings known as “The Acacias” and “Greenbank” including the stabling, cottage, paddock, and the strip of ground adjoining the paddock …. There is a frontage on to the London Road of about 270 feet, a depth of about 700 feet along the Redlands Road, and a width of about 340 feet along the Acacias Road. In making the offer of this site I withdraw my promise of contributing Six Thousand Pounds to the building fund of the college.‘

Palmer also declared that he was prepared to sell the houses and gardens of Nos. 32, 34, 36, 38 and 40 London Road for £4,000, thus providing an extra 240 feet of frontage.

On 19 January 1904, the College Council accepted the offer unanimously and the first removals from Valpy Street to what was to become today’s London Road Campus began in 1905. The annual calendar used the map below to illustrate the most convenient route between Reading’s two stations and the two sites.

Sources

Childs, W. M. (1933). Making a university: an account of the university movement at Reading. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd.

University College, Reading. Calendars, 1902-3, 1903-4, 1905-6.

University College, Reading. Official Gazette. No 33. Vol. III. 21st January, 1904.

University College, Reading. Official Gazette. No 34. Vol. IIi. 22nd February, 1904.

University Extension College, Reading. Calendar, 1897-8.