In December 1906, the driver of the 9:10pm train from Basingstoke to Reading noticed a sudden jerk as it passed under the Bath Road bridge where Berkeley Avenue now emerges onto the main road. Thomas Gauntlett, the Great Western driver thought little of it until he found blood and clothing under the tender on arriving at Reading Station.

A ticket collector was sent to investigate, and the body of a woman was found beneath the bridge. It was positioned in way that suggested she had lain across the rails. The deceased was identified as Eveline Marie Dowsett whose disappearance the same evening had already been notified to the police.

An article in The Berkshire Chronicle stated that she was a BA of Oxford who had taught at Reading High School and ‘Reading University College’. Readers were assured that, ‘by all who knew her she was held in the highest esteem.’

The Inquest

The Chronicle dwelt in detail on Eveline’s mental state. She had been distressed over the death of her sister Alice the previous March and had spent some time in an institution in Bath, although she had never been certified insane. On her return to Reading she had seemed much improved, but the family had been warned of suicidal tendencies.

Eveline had also been deeply troubled by her lack of religious faith. Strangely, this was represented by The Berkshire Chronicle as her being ‘A Victim of Religious Mania’.

Ellen Perkins, Eveline’s half-sister, quoted her as saying that she had wasted her life and blamed her disturbed condition on intensive study for examinations:

‘Nellie, I have not got the steady head you have; my head is rocky. I ought never to have gone in for these examinations; they have done all the harm. My brain is so excited; I shall never be right again.’ (The Berkshire Chronicle, 11 December 1906).

The Coroner recorded a verdict of suicide.

How much do we know about Eveline?

Eveline was born in Brighton in 1872, but the 1881 census shows the Dowsett Family as having moved to Reading. By 1891 they had relocated to 160 Castle Hill, their permanent address until Eveline’s death.

Other members of the household were her father Arthur, a brewer, her younger sister Alice, their sister-in-law Ellen Perkins, a cook and a footman.

Reading High School

The Chronicle referred to Eveline teaching at Reading High School. Between 1887 and 1913, this was the name of today’s Abbey School on Kendrick Road. There is no record, however, of Eveline having taught there, although it can’t be completely ruled out.

On the other hand, a Register of Old Girls in the school’s museum does list both Eveline and her younger sister Alice as pupils. The entry mentions an Oxford course in History as well as Reading’s University Extension College:

Census Data

Whether Eveline was ever employed as a schoolteacher isn’t entirely clear, but census returns during her lifetime reveal that at some stage she had been a trainee:

-

- 1881: Alice, age 5, Scholar; Eveline, age 9, Scholar.

- 1891: Alice, age 15, Scholar; Eveline, age 19, Student Teacher,

- 1901: Alice, age 25, Living on own means; Eveline, 29, Living on own means.

Teaching at the College

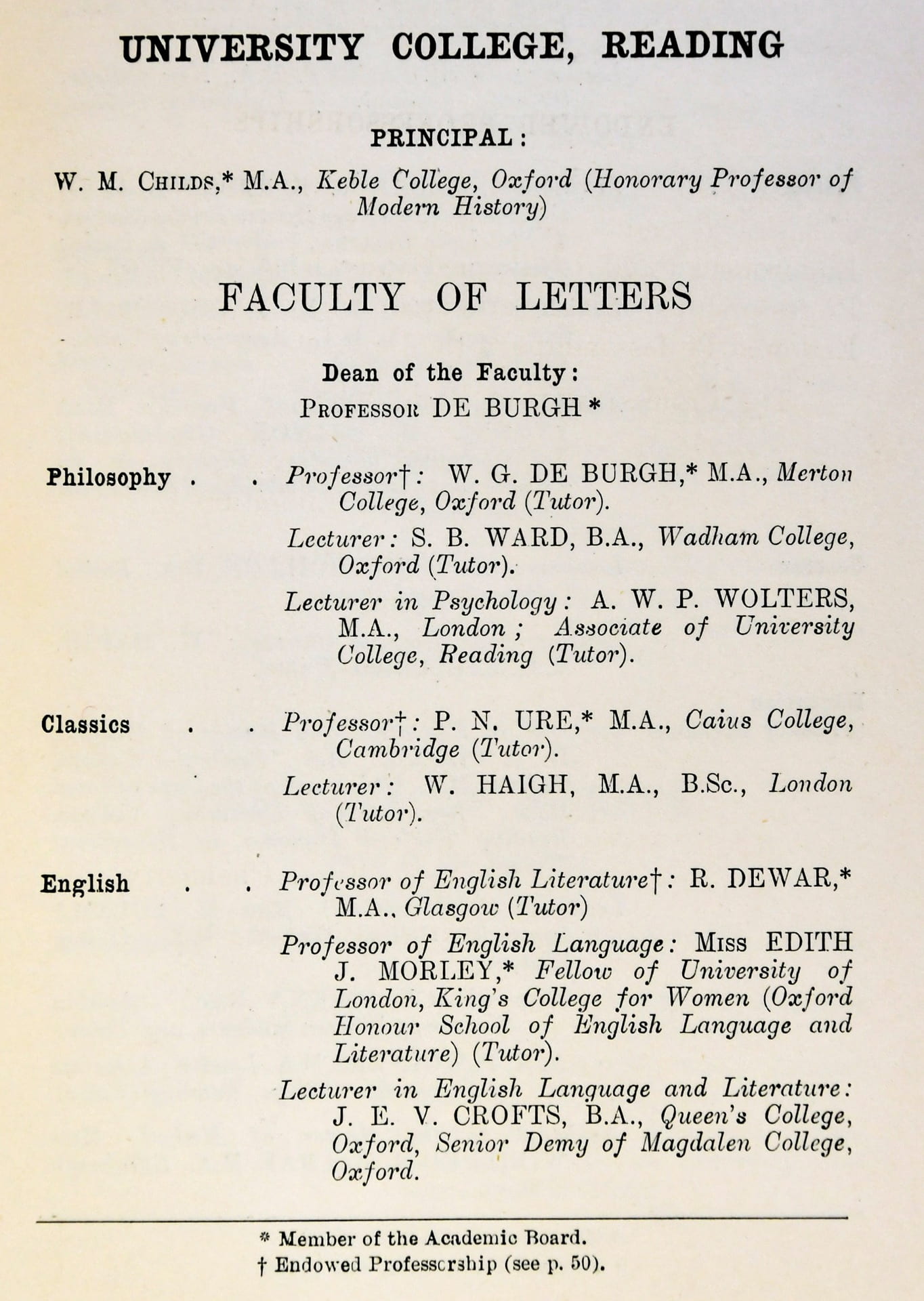

The Chronicle’s mention of Eveline’s teaching at the University Extension College can be confirmed. She did so during the academic year 1897-98. The College Calendar for that year (see below) shows that she had been allocated to the History Department under the guidance of W. M. Childs. Her job description was ‘Assistant for Normal Classes’, in other words, training or educating teachers – from 1893-95 the Education section had been known as The Normal Department, a common label at the time for teacher training institutions.

Education was not yet such a key part of the College’s business as it would become in 1899 when the Board of Education recognised it as a Day Training College. Nevertheless, staff were already contributing to courses for Uncertified Assistant Teachers and Pupil Teachers. And it was to contribute to the latter that Eveline had been appointed. She taught Arithmetic, English and Reading to first- and second-years.

Eveline as a Student at Reading College

In 1898 the University Extension College was renamed Reading College, and the Gazette for May 1902 (see below) reveals that Eveline Dowsett had been awarded the ‘Diploma of Associateship in Letters’. According to the regulations for the period, this meant that Eveline would have:

-

-

- passed a Preliminary Examination in English, Arithmetic and two other subjects;

- attended full courses in 4 subjects for 2 sessions, satisfying examiners appointed by the Oxford University Extension Delegacy at the end of each year.

-

She would, therefore, have been a student at the college for at least two years previously.

A Conundrum

The sequence of events in Eveline’s life raise a number of questions:

-

-

- 1891 (census): Student Teacher (age 19);

- 1897-98: teaching at Reading’s University Extension College;

- 1901 (census): living on her own means;

- 1900-02: studying for her Associateship;

- 1906: died.

-

What was she doing between leaving school and joining the College staff? Had she been working as an uncertified teacher? Did she at some stage obtain a teaching qualification?

According to a blog published by the Bodleian Libraries, the Associate Diploma at Reading was particularly popular with students wanting to become teachers because the examinations were accepted by the Government’s Board of Education as equivalent to teacher training exams. It is possible therefore that a combination of previous teaching experience and the Associateship left her fully qualified.

What we don’t know is how references to a BA in the newspaper article and to Oxford History Schools in her school record fit in. Whatever Oxford University examinations Eveline had taken, she certainly would not have been awarded a BA because female students at Oxford were unable to matriculate or graduate until 1920.

Staff at the Bodleian Library have searched the Index to Women Students (1878-1920), the Index to Registers of Women Students and the Index to Students Awarded Diplomas and Certificates (1900-1995) and have found no entries for Dowsett. So the mystery remains unsolved. Nevertheless, there are still some avenues to explore and the search continues.

The courses for pupil teachers

Towards the end of the 19th Century, increases in the supply of teachers in the Reading area failed to keep up with the rapidly expanding school population. According to Stuart Hylton (2007), a single teacher at the Tilehurst Board School in 1980 had to manage 122 children. Pupil teachers helped to fill the gap, although Hylton reports that in one case a pupil teacher and a monitor were expected to teach a class of 67.

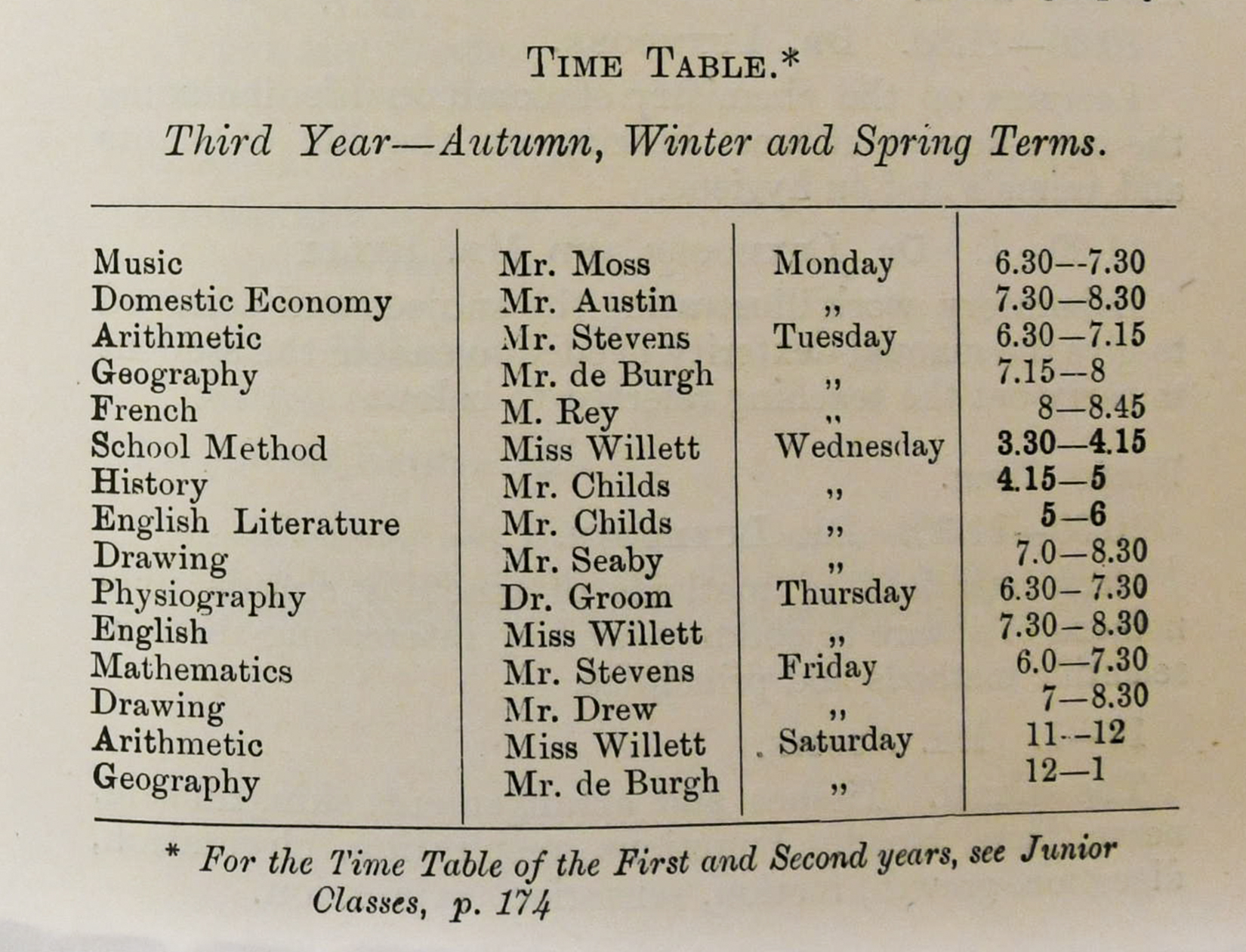

The University Extension College had been recruiting and training pupil teachers since it was founded in 1892. The courses were hard work for both the students and their tutors. The pupils spent all week in their schools, only to spend two hours every evening at the College plus three hours on a Saturday morning (see timetable above). Much of their spare time remaining was filled with homework!

The courses took four years, were approved by the Reading School Board and Reading Church Schools Council, and were inspected by H. M. Inspector of Schools. A fee of £2 per academic year was paid by School Mangers for each pupil.

If Eveline’s mental state was delicate, dealing with classes of exuberant pupil teachers would not have helped. In 1893 W. M. Childs joined the College. He was to become Eveline’s mentor four years later and, eventually, the University of Reading’s first Vice-Chancellor. Despite his illustrious future, the pupil teachers almost left him in despair:

‘As for the pupil teachers, they almost defeated me … Most of these young people were girls whose passion for whispering shattered me much more than the genial disorder of the handful of boys. I had been told that until lately all these pupil teachers had been taught on traditional lines by their own head teachers in their own schools, and that herding them into central classes was not popular… at first it was uphill work, and sometimes I returned to London more that half inclined to throw up my job.’ (Childs, 1933, pp. 3-4).

Thanks to

Dr Rhianedd Smith (Director of Academic Learning and Engagement, University Museums and Special Collections Services) for identifying this topic and passing on census material and the newspaper article.

The Abbey School for providing information about Eveline and her sister Alice from its records and for giving permission to reproduce it here.

Staff at the Bodleian Library, Oxford, for searching student records.

Georgie Moore, University of Reading Collections Officer, for information about women’s colleges and the history of women students at Oxford.

Sources

Childs, W. M. (1933). Making a university: an account of the university movement at Reading. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd.

Hylton, R. (2007). A history of Reading. Chichester: Phillimore.

Lady B.A’s Suicide. (1906, December 11). The Berkshire Chronicle.

Reading College. Calendar, 1900-1901.

Reading College. Official Gazette, No. 7, Vol. I. May 31st, 1902.

University Extension College, Reading. Calendar, 1897-8.