(This is part 2 of a 2-part post where a Jungian psychological approach is taken to analysing the history of the West’s relationship with the Amazon rainforest. I recommend you read part 1 if you have not already done so.)

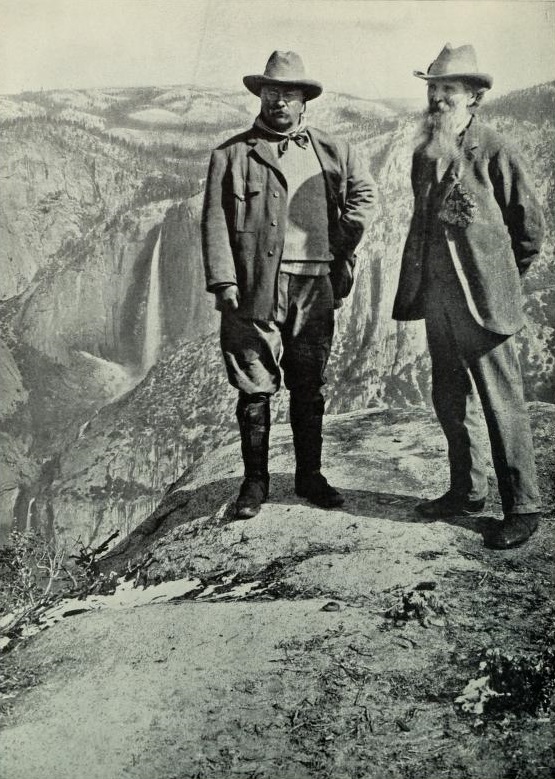

In the late 19th century thinkers like Muir and Thoreau fused insights from Eastern philosophy, Romanticism and natural science, sparking a public interest in ecosystems as spiritual and leisurely places. President Roosevelt established the National Parks system, officially designating certain landscapes as protected wilderness. Designations were partly pragmatic decisions to conserve resources but perhaps more importantly made on a landscapes ability to ignite the feeling of awe. Yellowstone National Park was the first wilderness protected area in the world, but the model spread rapidly across the globe making its way to the Amazon. From this combination of ideas rose the applied science of biological conservation. In the same way Amazonia became the archetypal frontier to Imperial expansionists due to its size and vegetative fecundity, it became the ultimate wilderness in need of protection, in the minds of the conservationists.

Rapid industrialisation and urbanisation during the 19th and 20th centuries are rightly held as main culprits in the widening disconnect between people and forests. However, the development of ecological science and conservation played a subtle role too by replacing the accumulated wisdoms people had with the landscape with shallower ideals of scientific instrumentalism and/or the innate goodness of pristine nature. A pernicious anti-human ideology developed among many conservationists. Human influence became antithetical to the wilderness ethic, the management ideal was to isolate conservation areas, keeping disturbance to a minimum, because if left alone, nature would prevail. Mass evictions took place, displacing thousands of peoples worldwide, including Amazonians. Intellectuals argued that soil fertility, heat and sheer vegetative biomass, prevented the development of civilization in Amazonia (see “Constructing Tropical Nature” pg. 17-24). This fact – that large areas of South America were destined to be places of nature, not people – would grip academia for the best part of the 19th and 20th century, while still holding sway over the public today.

From 1970 onward, a new breed of archaeologists and palaeoecologists discovered that past native populations in Amazonia were larger than previously realised. Many villages were large and sedentary, with regional connections; cultivation was usually intensive or semi-intensive; fertile soils were created; and useful tree species were propagated outside their native ranges. Evidence supports the claim that human management was intensively concentrated around rivers, select interfluves and inundated savannas. However, the majority of Amazonia remains unstudied and their remains more unknowns than knowns. Our view of Amazonia is undergoing radical re-assortment and as result there is a new risk of going too far in the other direction, placing undue emphasis on the role of humans in shaping Amazonia.

Tropical Palaeoecologists and Archaeologists, alongside the traditional Ecologists have given us much to think about. Despite the debate, academics and conservationists must account for the mistakes of the past and begin to engage in more serious discussions about forest management. It is only by seeing Amazonia as a human-nature hybrid that we can devise adequate forest management policies. Nature in the tropics is a heterogeneous thing, a mix of the natural and the artificial, the human and the nonhuman. The human inhabitants of the tropical rainforests (estimated at 50 million people across the globe) have their claim to occupy space. These people have the very dangerous but very necessary right to modify and even destroy tropical forests.

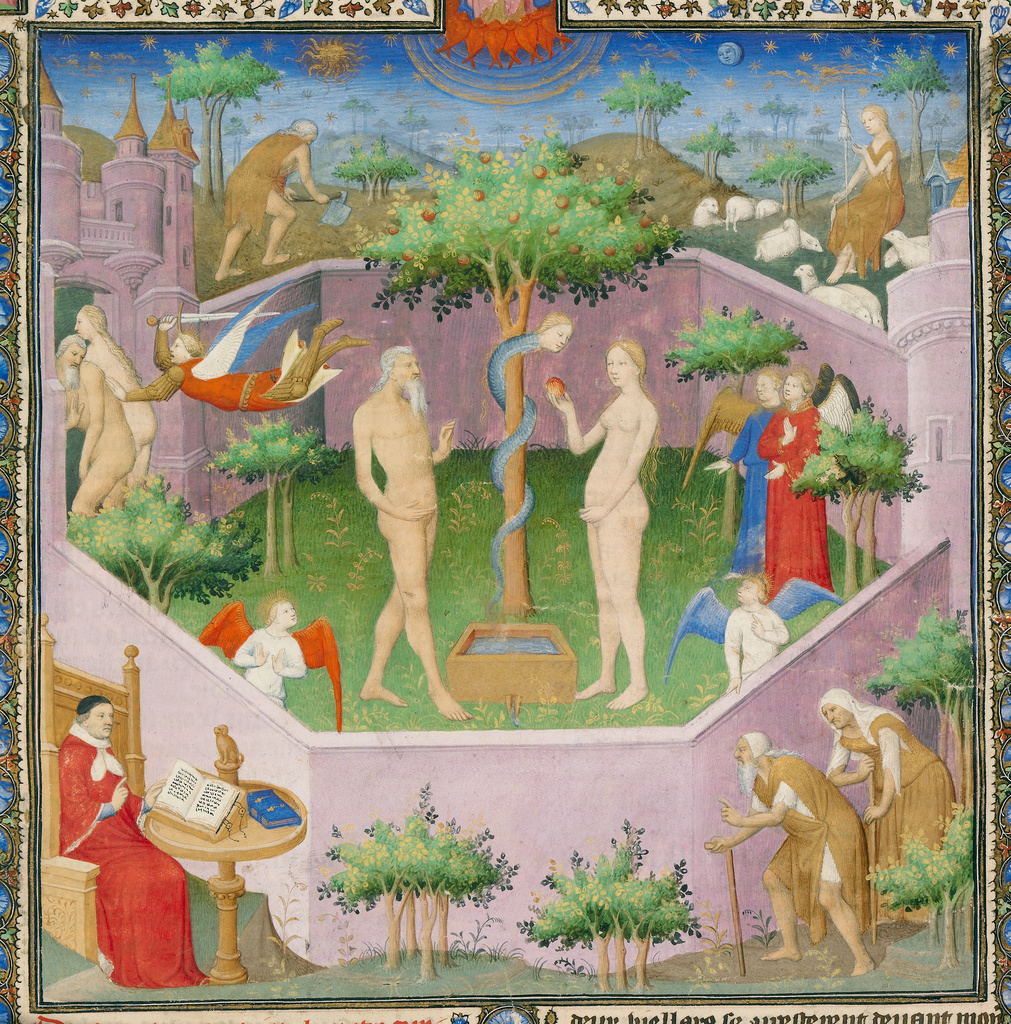

We find ourselves coming full-circle, advancements in forest science must be tempered alongside the wisdoms of our ancestors. Take for example the Garden of Eden from Genesis. Eden also referred to as paradise, is descended from the Old Iranian word *paridayda- “walled garden”. The wall is culture and order while the garden is nature and chaos. When nature is controlled, its benevolent aspects can flourish, with invigorating results for the human body and psyche. As a human invention and aesthetic escape, to be successful as well as environmentally sustainable, that control must respect ecological theory and process. The relationship between people and ecosystems is to be one of gardening, where the promotion of environmental services is top priority. Thinking in terms of a garden may be a useful way of rethinking the human relationship to the natural world in a period when concepts of untouched “wilderness” and “pristine nature” have lost credibility.

Medieval manuscripts often depict the Garden of Eden enclosed by a wall. Such art demonstrates the spiritual nature of ecosystem management by people (Manuscript by the Boucicaut Master, 1415).

James