Written by Adam Koszary, Project Officer.

Yesterday we picked up our newest acquisition: a pair of wellies. It seems strange that a museum of English rural life wouldn’t have this icon of the countryside already in the collection, but they never really came onto our radar as an endangered object. The welly has never needed saving as it’s managed to persevere as a popular and versatile piece of footwear from its inception in 1817 as a military boot, through to being the favoured outdoor footwear for farmers and to the present day as a quasi-glamour item associated with festivals.

It is these last two associations which led us to the pair of wellies pictured above. They have been well-used over a ten year period by Michael Eavis, Somerset dairy farmer and organiser of Glastonbury Festival. Despite the massive popularity of the festival which Michael has been running since 1970, he is first and foremost a farmer and the infamous Glastonbury mud is still caked on the soles of his wellies now sitting in the Assistant Curator’s office. His dairy herd are the highest yielding in Somerset and the 4th highest in the UK – and if he milked them three times a day rather than two he could even be the highest in the country. He has a great enthusiasm for his farm, his cows and the people who look after them. However, as founder of Glastonbury he has also overseen the birth of the welly as a practical fashion item, with revellers mucking about in the mud on his farm splashed across papers and TV reports (and subsequently onto the national psyche). Celebrities hounded by the paparazzi at the festival have their outfits scrutinised by tabloids and magazines, leaving the Hunter wellington boot to come out top in the fashion stakes. Festivals are not only a way for a select few farmers to earn extra income, but also a principal way in which people now enjoy the countryside.

Michael is a farmer first – his farm dominates the view from his garden, with the Pyramid Stage in the distance.

There is one small hitch though: these wellies are French. Should this matter, as a museum of English rural life? I don’t think that it does, but I’m well aware that others may think differently. The message these wellies are meant to illustrate – that they have shifted in the public mind from practical farmers’ shoes to festival-goers’ shoes – is not affected by their origin. Michael Eavis is English, as is his farm, and presumably the shop he bought them in was also English (we’ll be ironing out these details in an interview later this year).

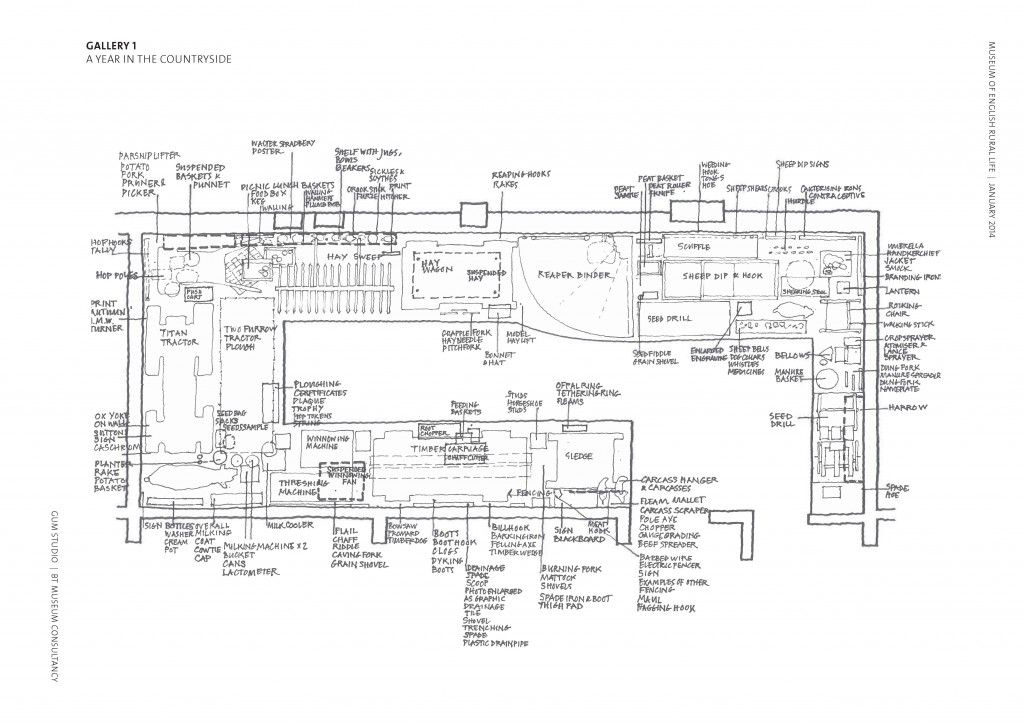

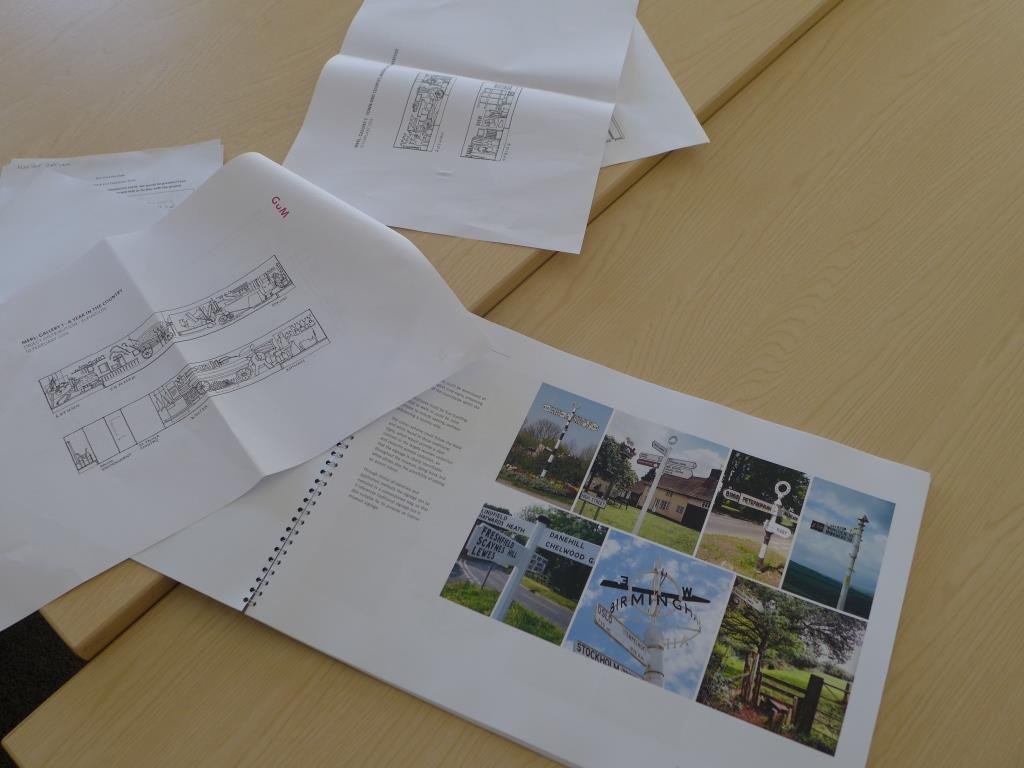

This is an issue which I think we will encounter in various forms in the new displays as part of Our Country Lives. There are numerous stories and facts that we want to talk about with our visitors, but for some of these we may not necessarily have the objects to illustrate them, or the objects we have may have a difficult provenance (e.g. they are not from England, or we don’t know who owned them or where they’re from). Should this mean, then, that we don’t talk about certain issues or facts? It shouldn’t, as for every topic we don’t have an object for there is a wealth of archives, photographs and videos which we can use instead. In the case of these specific boots, I think they remain valid in the sense that they show the international side of English rural life, and our place in a new, globalised world market. To ignore the international links and global events that affect English agriculture and the economy would be a dishonest way of exploring English rural life, and as such will still feature in the new galleries. We are continuing to research and plan these galleries, but once we approach our final version we will be sure to let you know all about them on this blog!