Sit back with a cup of tea and a piece of cake (of course) and take a few minutes to read this fascinating post by Assistant Curator, Dr Ollie Douglas, on the little known cake-related collections at MERL (and elsewhere)…

Here at the Museum we’ve been eating rather a lot of cake. The frenetic activity of the annual MERL Village Fete was fuelled largely by cake, either produced for the baking competition or purchased along with cream teas. Add to this a flurry of summer birthdays and a series of project successes and you’d be forgiven for thinking that we do little other than eat tasty confectioneries all day long. I hasten to add that this is, of course, not true and that we not only work extremely hard but only ever eat cake at a safe and conservator-approved distance from our collections!

If you are tucking into a piece of Victoria sponge right now and muttering that a museum dedicated to rural life should have no reason to acquire cake-related objects then I’m afraid I’m going to disappoint. Not only do we have extensive collections on the theme of cake but we probably have sufficient holdings to fill all the cake tins of Mary Berry herself. Inspired by my colleagues and their growing addiction to baked goods as well as by a recent discussion concerning cake and collections I set out to investigate what interesting nibbles I could find in the storerooms of MERL.

In the archive we have several photographs of Princess Marina’s bridal cake, as taken by local photographer Philip Collier (1881-1979), shortly before the royal wedding in 1934. The cake was made by the local firm Huntley and Palmers, who were better known for their biscuits but evidently dabbled in cakes as well. Collier’s work forms an important strand of a new collaboration with Reading Museum entitled Reading Connections.

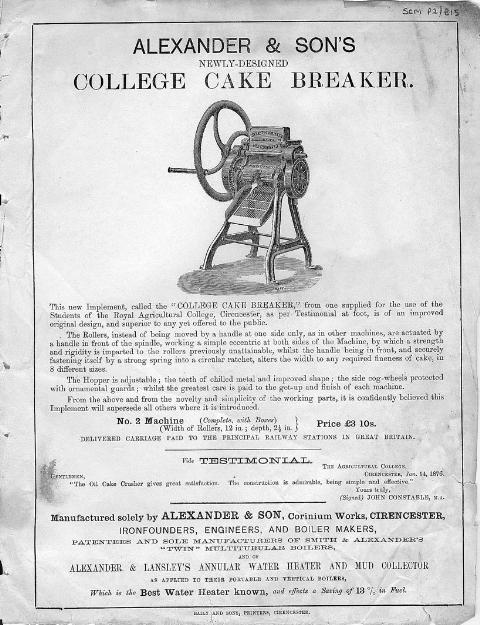

Elsewhere in the archive we also hold trade records relating to the production, promotion, and distribution of cake-breaking equipment, including a cake-breaker promoted by Alexander and Sons of Cirencester. This refers to a different, altogether less appetising, sort of cake. Oil cake was made from the material that remained after oil was extracted from crops such as oil seed rape and linseed. The resultant blocks were sold as animal feed but needed to be broken up before being fed to livestock. Cake-breakers were used to grind up larger chunks into pieces that animals could then eat.

As far as the object holdings go, we have further items relating to animal cake, including an actual cake-breaker (MERL 53/197) from Langley, Warwickshire, which would have been used to prepare animal feed in just the way described. However, let me now return to items connected with cakes intended for people rather than animals. The collection of Lavinia Smith yields a rich seam of cake-related objects. Smith was an American-born collector who gathered items to characterise life in the village where she lived, East Hendred. Her collection forms another strand of the Reading Connections project. She was concerned as much with life inside the farmhouse or cottage as she was with work in surrounding fields and hence the objects include numerous items of hearth furniture and cooking utensils such as a girdle plate (MERL 51/520) that would have been suspended over an open fire and used to bake oatcakes, scones or cakes. She also collected a so-called ‘salamander’ (MERL 51/751) given to her by the local blacksmith, which comprised an iron bar ending in a flat plate that pivoted on a stand and was heated in the fire until red hot whereupon it was used for browning pastry, mashed potato and cakes.

Gingerbread mould, as collected by Lavina Smith and bearing a striking resemblance to a Biddenden cake mould (MERL 51/536)

Although it’s not strictly speaking cake-related, Smith also acquired an object described by John Denniss—the baker who passed it to her—as a gingerbread mould (MERL 51/536). Denniss’ family had reputedly been bakers in East Hendred for 200 years and it had presumably been used by them. My colleague Laura recently retrieved it from the store in preparation for a visit by an overseas researcher interested in biscuit, cookie, and gingerbread moulds, and on closer examination I realised that it bears a striking resemblance to the design of the Biddenden cake. These were handed out as part of a charitable dole at Biddenden, Kent, which is said to have been founded by the conjoined twins Eliza and Mary Chalkhurst in the 1100s. Although the story has been largely discredited, it is a potent example of how cakes are easily incorporated into powerful local traditions.

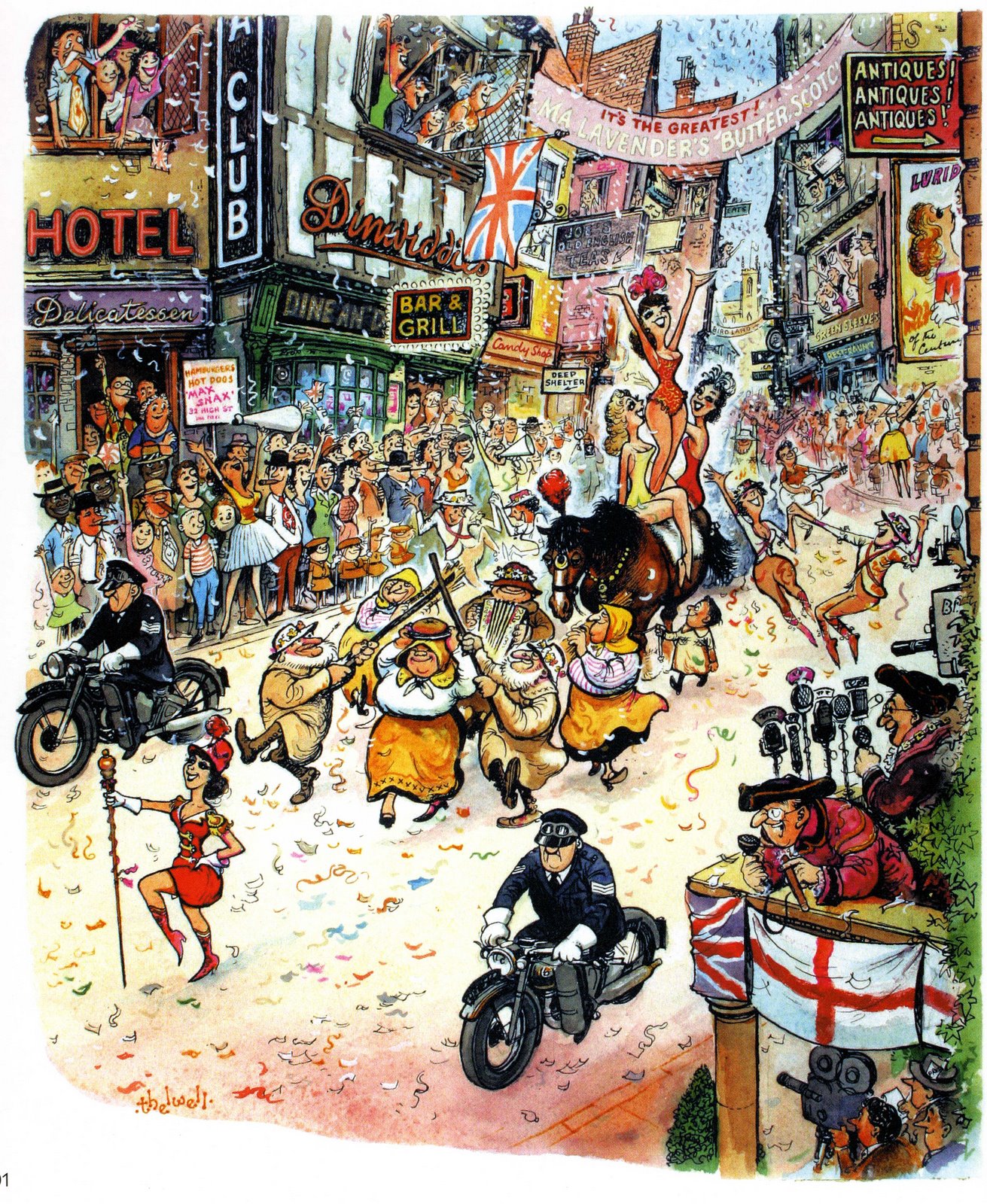

A piece of artwork (MERL 2009/28) purchased through MERL’s recent collecting project, offers a slightly different take on the link between cake and tradition (MERL 2009/28). This picture by well-known cartoonist Norman Thelwell (1923-2004) offers a wry comment on the invention of tradition. At the centre of the image some rustic-looking yokels appear to be hitting a cake with rough-hewn sticks. This is a reference to cake-based customary practices and to the tradition of beating the bounds, here combined in a characteristically comical, mystifying, and Thelwellian take on English culture.

This image harbours a subtle air of poking fun at folk revivalists and at people who enjoy pastimes that form part of this movement, such as Morris dancers and mummers. Just for the record, MERL remains extremely pleased to be able to host Morris dancers at its Village fete every year, and here at the Museum we warmly encourage links between cake and tradition, though perhaps in a less violent-looking way than Thelwell’s portrayal!

Having delved deeper into MERL’s own slice of cake history I should confess that I have a soft spot for collections that relate to cake. I began my career at the Pitt Rivers Museum at the University of Oxford, which houses an extraordinary collection of ceremonial cakes. I think you can still view some of these objects, packed into a drawer on the ground floor. I like to think that these items were left by early curators to slowly desiccate, no doubt offering a tempting distraction from other more scholarly activities. However, these early custodians resisted the urge to snack and the items were preserved to stand as testimony to the inventive baking skills of our forebears, to the rich multiplicity of food-related cultural practice, and to the (sometimes surreal) interests of anthropologists and folklorists of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries.

In the course of my own PhD research I came across references to a collection of ceremonial cakes of the British Isles that was exhibited during the International Folklore Congress of 1891, as held at Burlington House, London (see this list of items exhibited, as published in 1891). This collation of so-called ‘feasten cakes’ was coordinated by a member of the Folklore Society called Alice Bertha Gomme (1852-1938). Gomme was the wife of folklorist George Lawrence Gomme (1853-1916) and was a significant figure in her own right, serving as Secretary to the Entertainment Committee of the 1891 Congress and going on to become a leading expert in the study of children’s games as well as traditional food.

Some of the early collections amassed by curators at MERL sought to offer a comprehensive and regional overview of the whole of England; these include the wagon holdings (as discussed in a previous post) and perhaps most famously the smocks (also mentioned in an earlier post). Much like these later examples, Gomme’s vision for the cake display was clearly one that was comparably inclusive. As this map shows, with the exception of Ireland the coverage was relatively comprehensive and the the provenance of the ceremonial cakes featured is clearly indicative of a desire on Gomme’s part to be as representative of the United Kingdom as possible.

Map showing distribution of British ceremonial cakes exhibited at the International Folklore

Congress of 1891 (Oliver Douglas, ‘The Material Culture of Folklore’ – unpublished DPhil Thesis, p.87)

The temptation of this edible display was such that it was not simply illustrative and a significant number of these delicacies were purchased by the Entertainment Committee in order to be served to hungry delegates attending the Congress. As the historian of the folklore movement Richard Dorson later put it, the Congress offered “a feast for the eyes, the ears, and even the mouth.” I wonder if perhaps the staff at MERL should take a leaf from Gomme’s recipe book and begin to think more carefully about the foodstuffs we serve at the Village fete and why we serve them. What can different types of cake tell us about English rural life? Are ceremonial and feasten foods still important markers of who the English are and what it means to be a part of a rural way of life? Are we contributing to the continuation of rural cake-baking traditions that the Women’s Institute would be proud of and are we helping to reinvent traditions in a way that Thelwell might have found amusing? I hope so.

Finally, and far more importantly, I wonder whose turn is it to bring in the baked goods (and who ate the last slice of the chocolate cake I saw in the staff room?!).