After an exploratory visit to Kazakhstan (reported here in 2009), Heinrich obtained funding from the Wenner Gren Foundation (USA) for an initial excavation season in 2011 at Dzhankent, just east of the Aral Sea. This proved highly successful in showing the potential of the site for a major project, and it provided new dating evidence (see the interim report).

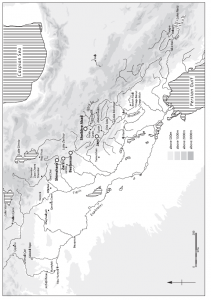

The first series of radiocarbon dates from Dzhankent, and pottery finds from sections inside the town walls have key implications for the starting date of the town: its origins are not in a 9th century fortified capital of intrusive Turkic nomads (which is suggested by writings of 10th century Arab geographers), but in an open settlement of a local sedentary fishing population in the 7th century. This is changing our ideas on the medieval urbanization of this region, and instead of looking for explanations in nomad state formation started by the arrival of the Turkic tribe of the Oguz from Mongolia, we now have to look for other factors two centuries earlier. And the most important event affecting this region on the river Syr-darya in the 7th century was the establishment of the northern Silk Road along the river, around the northern shores of Aral Sea and Caspian Sea, and continuing from there southwest to Byzantium, or northwest along to Volga linking into Viking trade routes in Eastern Europe.

Now Heinrich has obtained funding from the Deutsche Forschungs-Gemeinschaft (DFG) for a major three-year project to explore the relationship between this deserted town on the steppes close to the Aral Sea, and the wider world of trade in the 7th to 11th centuries. The main collaborative partner will again be the regionally important Korkyt-Ata State University of Kyzylorda. There is a whole series of key questions to be tackled: How long did that fishing village exist on this spot before it was turned into a trading site? Does the archaeological evidence suggest the presence of traders from the southern Silk Road civilization of Khorezm (Chorasmia)? There are substantial quantities of Khorezmian pottery in the occupation layers, and even the lay-out of the later fortified town appears to copy a Khorezmian type of urban lay-out. When did the Oguz nomads arrive to make this trading town their capital? Did they live in the citadel? Did they contribute livestock trade to the regional exchange patterns? Where are the cemeteries which might prove or disprove the multi-ethnic nature of this town? Where is the river channel which must have run past Dzhankent before the delta dried out, and where is the river port implied by a short note in one 10th century text? Is the hump outside the east gate of the town a caravanserai? And why did the town falter in the 11th century?

Professors G. Astill (UoR, right) and J. Staecker (Tübingen, left; † 2019) visiting the site in 2011.

These questions require a multidisciplinary approach, and Heinrich envisages close collaboration of the German and Kazakh archaeologists with geophysicists, geomorphologists and soil scientists from Russia, American animal bone specialists based in Germany, a German radiocarbon laboratory, and numismatists and historians from Britain. It is hoped that the answers will have an impact not just on debates within Central Asian archaeology, but well beyond. After all, the 7th to 11th centuries AD were the period when a trading network flourished in northwestern Europe – and Dzhankent, with its connection to the northern route leading to the Volga, may have provided a link from the Silk Road to the East European and Scandinavian trade network of this time.

Update on new fieldwork in Kazakhstan (2018-19)

Since 2018, the international multi-disciplinary team of the Dzhankent project has been working hard on site as well as in stores and labs, helped by local workers and student volunteers. Several carefully placed trenches have revealed small houses of Central Asian type, one of them with a fragment of decorative wall painting. Large buildings such as temples or palaces have not been discovered so far. The southern town wall was found to stand on top of an occupation layer with 8th century pottery, implying the existence of an open settlement before the building of the walled town in the late 9th or 10th century. Finds from the buildings confirm the presence of three main pottery styles which suggest a mixed population made up of locals, nomads, and southern traders. Regular links to the south, by then Islamic, are also shown by a 10th-century pot with three chicken eggs bearing Arabic lettering, by about half a dozen vessels with Arabic graffiti, and by Samanid coins of the 10th century.

Extensive prospection (magnetometry, electric resistivity, electrotomography, georadar) and manual coring in 2018 highlighted the dense arrangement of buildings within the town walls, and a depth of occupation layers of several metres across the site. So, in order to obtain meaningful information on the history of Dzhankent within the project period of three years, the team changed its fieldwork strategy in 2019 by shifting the emphasis to coring. Our geomorphologist (Prof. Andrej Panin) laid a grid of coring points across the site and used a lorry-based mechanical drill to obtain cores down to natural, through all occupation layers. More than 100 samples from these cores are currently being C14 dated and analysed by soil scientists for their composition, aiming for an outline history of occupation of all areas of the town.

But there is already enough information to draw up a provisional model of the origins and development of Dzhankent. The later town of the 10th century grew out of a large fishing village which, as early as the 7th/8th centuries, had trade links to the south, to the Iranian civilization of Khorezm (Chorasmia) on the Amu-Darya river. Khorezmian traders became interested in Dzhankent because it was located on the river Syr-Darya which, from around AD 600, was part of the route of the Northern Silk Road, connecting Central Asia (and ultimately, China) to the Volga, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the Mediterranean. Turkic nomad rulers of the Oguz tribe instigated the building of a fortified town at this location around AD 900, making it the centre of their steppe empire. Dzhankent thrived for more than a century, perhaps also playing a role in the north-south slave trade from the Baltic region and Eastern Europe to Central Asia, until it was abandoned in the 11th or early 12th century – for reasons which we still have to find out.

Dzhanik: the earliest cat on the Northern Silk Road

The sharp-eyed archaeozoologist on the team, Dr Ashleigh Haruda (Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, Germany), spotted the bones of a feline while looking through the large quantities of animal bones from the site. She immediately realized the significance of the find and assembled an interdisciplinary team to extract all possible information from the largely complete skeleton. As a result, we now have an astonishingly detailed biography of a tomcat that lived and died in the late 8th century AD here in a village on the Syr-Darya river. X-rays and 3D imaging revealed a number of healed fractures of bones, meaning that humans must have looked after the animal while he was unable to hunt. In fact, he was looked after quite well: he had reached an age of several years, helped by a high-protein diet, probably fish (as shown by stable isotope analysis). And his DNA shows that he was most likely a true representative of the species Felis catus L., the kind of modern domestic cat – not a tame wildcat. This makes him the earliest domestic mouser in Eurasia north of Central Asia and east of China, about 1200 years ago.

Full open-access publication: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-67798-6#citeas