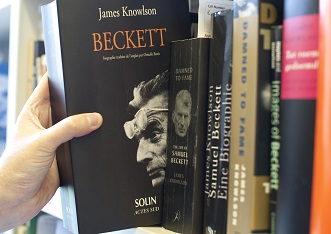

It has been a very sad week for all of us involved with the Beckett Collection, as it marked the passing of two people associated with him, as well as the 25th anniversary of his death. Billie Whitelaw is widely recognised as having been Beckett’s favourite actress and the foremost interpreter of his work. Our colleague Professor Anna McMullan paid a fulsome tribute to Billie and noted her long association with the University of Reading.

The news of Billie’s death came on Sunday. On Friday we had announced that the University of Reading and the Beckett International Foundation had purchased the archive of Billie’s work with Beckett, and we were (and remain) full of excitement about that. The purchase has been the result of Special Collections staff working closely with academic colleagues to raise the necessary funding. It is this type of collaboration that created the Beckett Collection here at Reading and that helps to sustain and enhance it.

On Sunday we also learned of the death of veteran photographer Jane Bown. Her encounter with Beckett was less collaborative than those of Billie Whitelaw: Bown surprised him in an alley outside the Royal Court Theatre after he had spent the day avoiding her lens. The result was a portrait that has become one of the most iconic images of the author.

The co-incidence of these two extraordinary women dying on the same day perhaps enables a moment to reflect on the strange and different ways in which works of art comes to be “born”. Billie Whitelaw’s brilliant interpretations of Beckett’s work were the result of long rehearsal periods and many hours of discussion, and of a close, friendly association – Dr Mark Nixon has called it a “crucial working relationship”, and the archive will throw more light on exactly how they worked. Jane Bown’s incredible image was certainly not the result of a collaborative venture – it was spontaneous to a large extent. In some ways it is a reminder of the fable about Picasso charging an exorbitant sum for a quick sketch (“It took me my whole life”).

While mourning their passing, we celebrate the extraordinary lives of these three people and the incredible art that their encounters – both long and short – generated.