Illustration of a Herculanean dancer. From: Ottavio Baiardi. The antiquities of Herculaneum. London: S. Leacroft, 1773.

Although Johann Joachim Winckelmann may not be a household name today, his influence on British art, design, and architecture was profound. Our new exhibition, ‘From Italy to Britain: Winckelmann and the spread of neoclassical taste’, tells the story of his contribution to the revival of classical arts and culture in Britain in the 18th and 19th centuries. In this post, Professor Amy Smith, one of the exhibition curators, explains how Winckelmann’s discoveries in Italy influenced and inspired generations of British artists, craftsmen and architects.

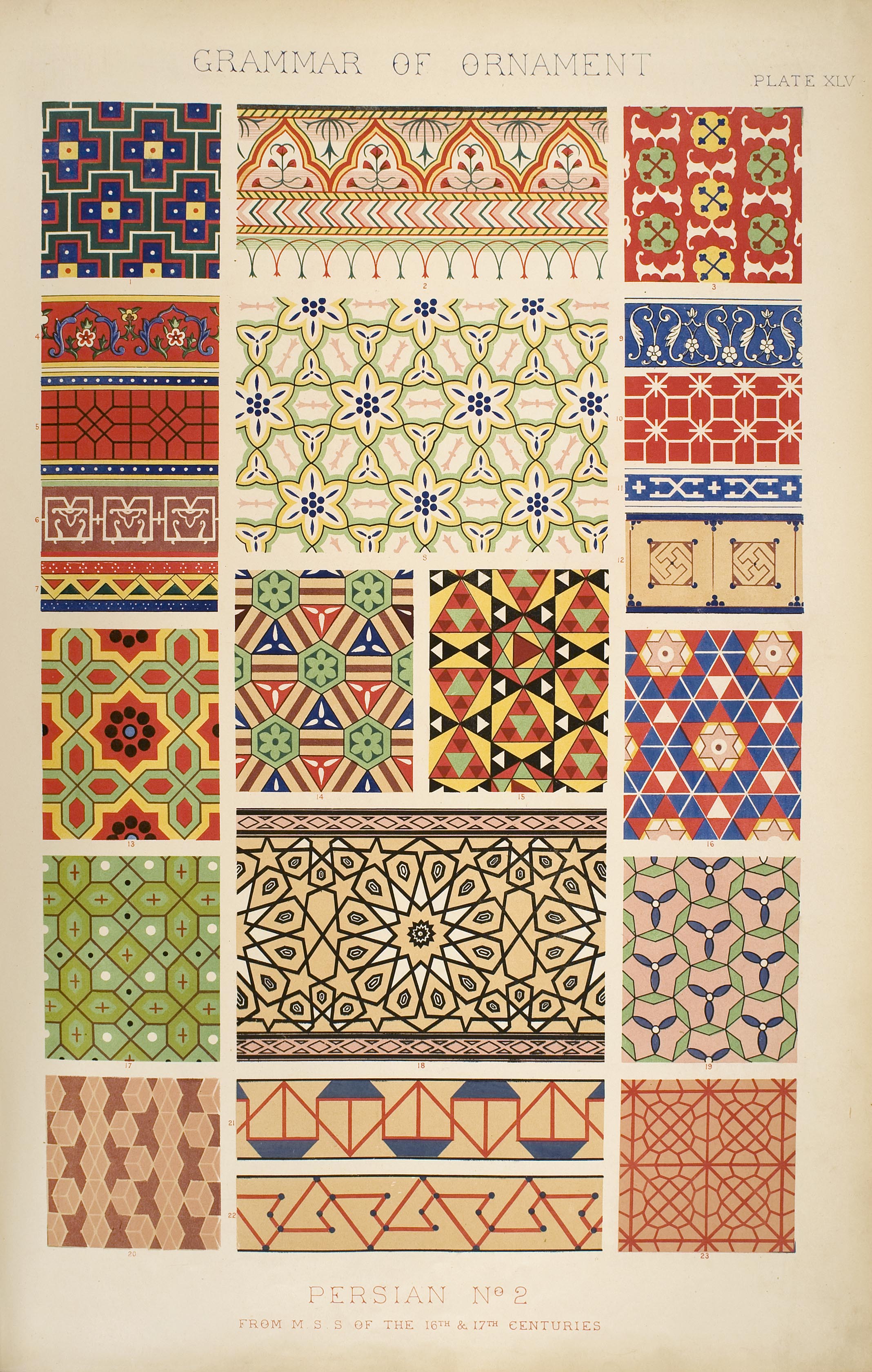

Like many antiquarians of his day, Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768) first learned about the Classics through immersion in literature. As a teacher then librarian in his native Germany, Winckelmann encountered the ancient world primarily through literary texts, as well as the souvenirs—coins, gems and figurines—Grand Tourists and other travellers had brought north from their visits to Italy. Once he arrived in Rome, where he rose to prominence at Prefect of Antiquities in the Vatican, Winckelmann studied the remains of Greek, Graeco-Roman and Roman art on a larger scale. Through personal contacts, letters and other writings, Winckelmann influenced his and subsequent generations of scholars, aesthetes, collectors, craftsmen and artists both within and beyond Italy.

The judgment of Paris. From: John Flaxman. The Iliad of Homer. London: Longman, 1805.

Winckelmann’s influence came to Britain through decorative designs in country houses that copied the style of wall paintings found in the excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum, on which he had reported. His influence is also visible in John Flaxman’s adaptations of classical and neoclassical images in drawings that illustrated the works of Homer and reliefs that decorate Josiah Wedgwood’s jasperware.

Winckelmann’s writings also encouraged an interest in Greek architecture and architectural sculpture, which was copied and adapted, for example, in Oxford’s Radcliffe Observatory. The upper story of this remarkable building, designed by Henry Keene in 1772 and completed by James Wyatt in 1794, copies Athens’ octagonal Tower of the Winds, with reliefs that emulate Wedgwood’s jasperware friezes.

The Tower of the Winds. From: James Stuart and Nicholas Revett. The antiquities of Athens. London: Haberkorn, 1762-94.

In the next generation architects continued to incorporate Hellenising elements into monuments such as Reading’s Simeon Monument (designed by Sir John Soane in 1804) and Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum (designed by Charles Robert Cockerell in 1845). The latter incorporates casts of the original friezes for the Temple of Apollo Epikourios at Bassae, the originals of which were found by Cockerell and acquired by the British Museum. Knowledge of Greek architectural reliefs in the British Museum was disseminated on a smaller scale through engravings and miniature casts designed, manufactured and sold by John Henning (1771–1851).

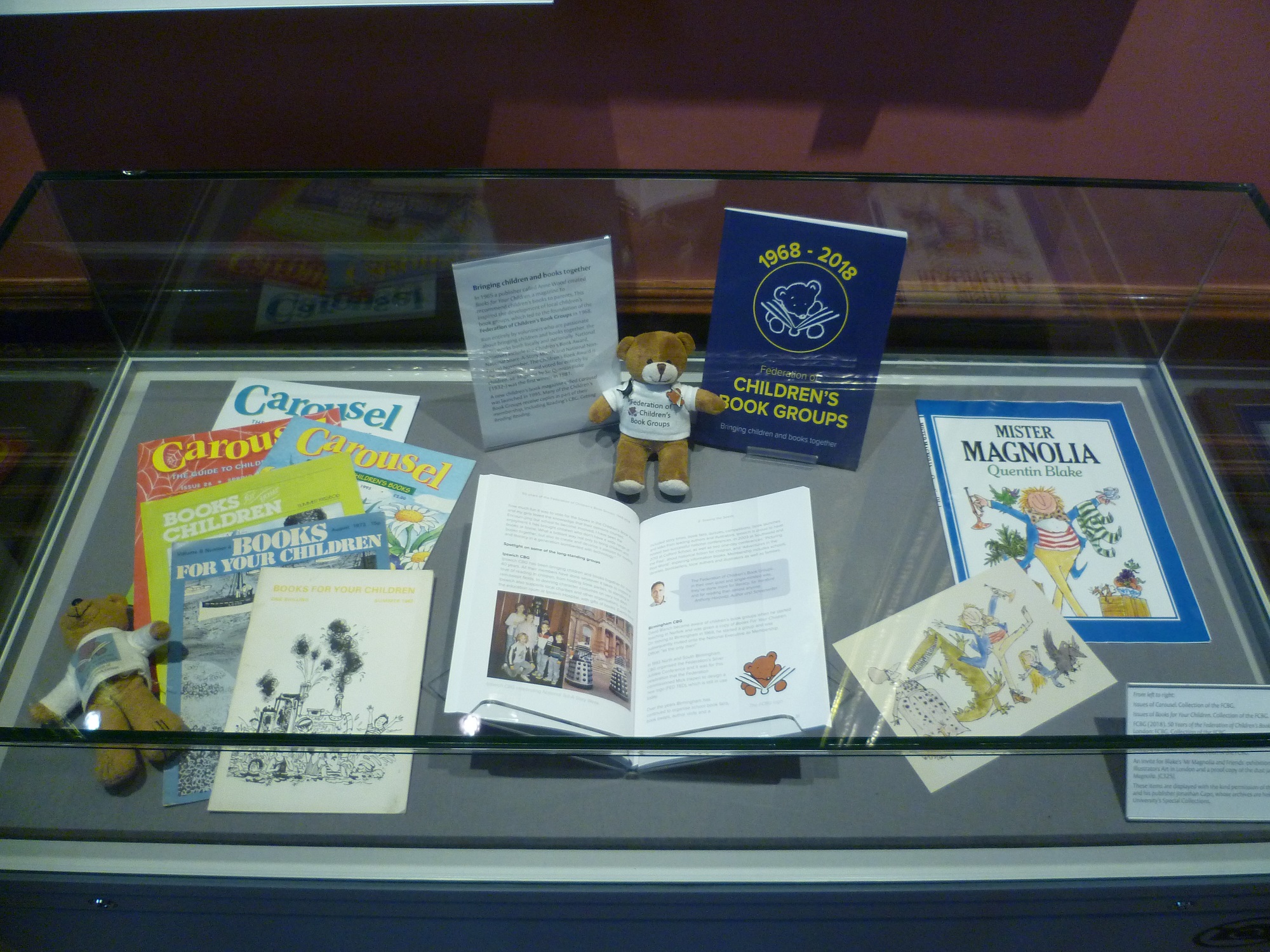

The exhibition at Special Collections, From Italy to Britain: Winckelmann and the spread of neoclassical taste, displays some of Winckelmann’s letters, 18th–19th century printed volumes and drawings and relevant artefacts, ancient and modern, that illustrate Winckelmann’s broad influence. The exhibition, a collaboration of University of Reading’s Ure Museum of Greek Archaeology (www.reading.ac.uk/ure) with Special Collections, runs from 15 September through 15 December 2017.

For information on opening hours and how to find us, please see our website.

For information on opening hours and how to find us, please see our website.

All images © University of Reading Special Collections

For information on opening hours and how to find us, please see

For information on opening hours and how to find us, please see