Written by Adam Lines, Reading Room Supervisor.

Before I started working at the University of Reading Special Collections, I spent a year in Grasmere working with the collections at the Wordsworth Trust. Before that I studied for a BA and an MA in English Literature and centred both of my dissertations on William Wordsworth. So by the time I left Grasmere at the start of 2015 it’s fair to say that I had the poet, his work and legacy firmly etched in my mind. My first search on the University of Reading Special Collection’s online catalogue was, not surprisingly, for ‘William Wordsworth’. To my delight there was a result: a single letter written by Wordsworth from 1820. The majority of original Wordsworth manuscripts are housed by the Wordsworth Trust but a few can be found scattered in archives across the world. The reason an example can be found in Reading is because it is part of the Longman Group Collection, the firm responsible for publishing much of Wordsworth’s work during his lifetime.

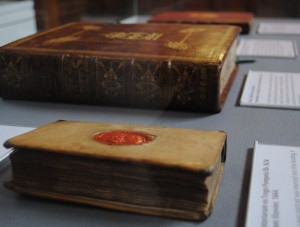

The letter doesn’t stand alone. It is housed in a small volume with other letters to Longman by Wordsworth’s sister Dorothy as well as his friend Samuel Taylor Coleridge. It belonged to R. G. Longman and these letters were clearly treasured by the Longman family as the volume was created especially to house them. You’d be forgiven for thinking that the volume contained only letters written by Coleridge as his name is the only one to grace the spine. A note inside the cover states: ‘4 ST Coleridge letters left to me by my uncle, T. N. Longman’. A further note underneath this was added many years later recording the addition of the letters by William and Dorothy. Given the strong bond of love and friendship between the three of them, it seems only fitting that the letters should reside together.

The inside cover of R. G. Longman’s volume of letters, with the inscription ‘4 ST Coleridge letters left to me by my uncle, T. N. Longman’.

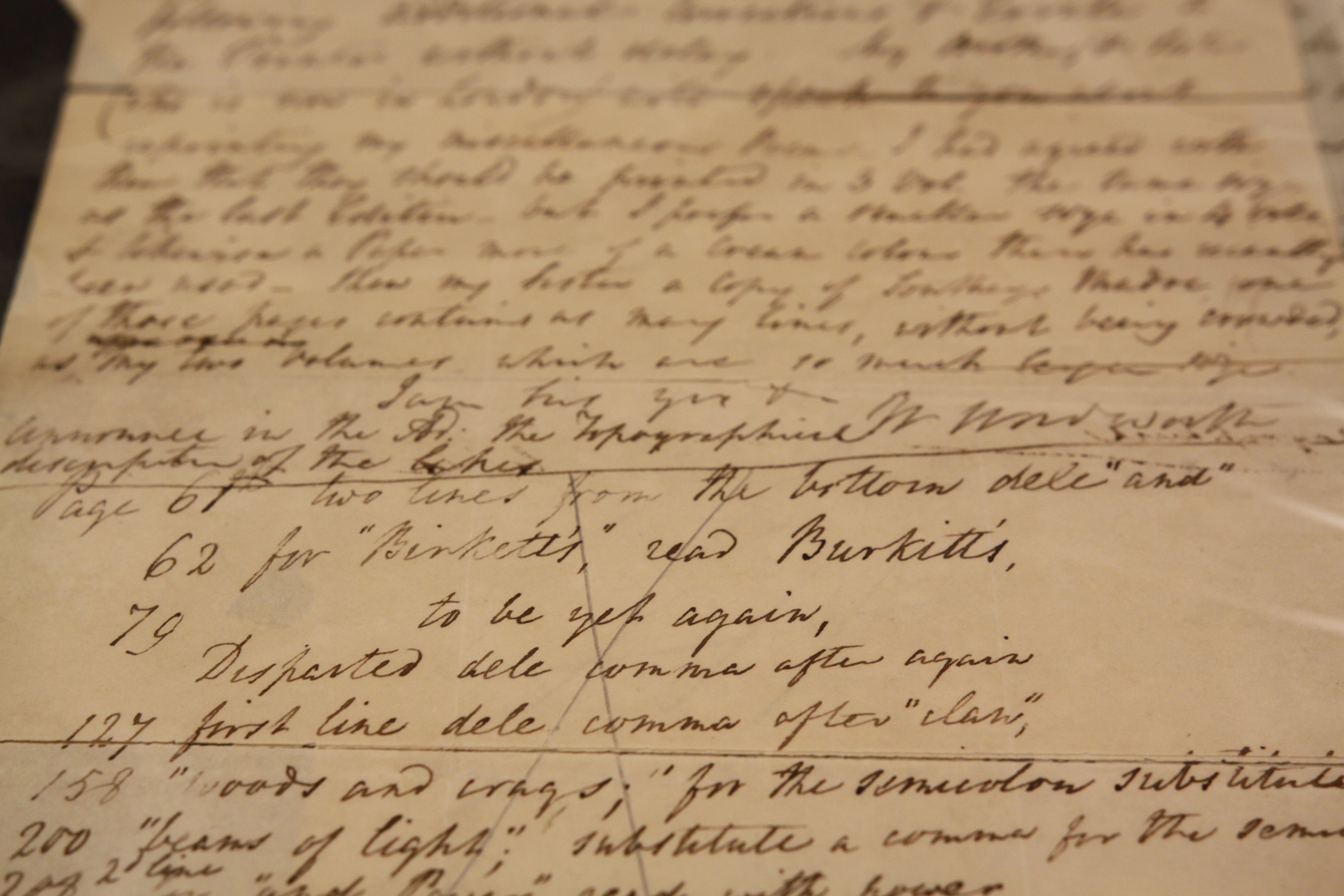

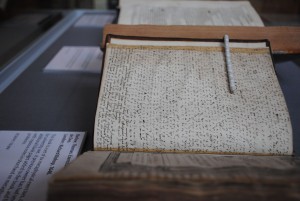

The year 1820 saw Wordsworth at a mid-point in his life as a writer. His ‘golden decade’ (1799-1808), during which he wrote the majority of his greatest works, was behind him and widespread fame and notoriety was still a few years ahead. On the 11 April 1820 he wrote to Longman asking them ‘to transmit the following additional corrections and Errata to the Printer without delay.’ The alterations were for The River Duddon, a series of sonnets about the river in his native Lake District following it from its source to the sea. He was also concerned about the reprint of another of his volumes, Miscellaneous Poems, and gave precise instructions as to how he wished it to be printed. After initially favouring three volumes, he wrote ‘I prefer a smaller size in 4 vols. and likewise a Paper more of a cream colour than has recently been used.’ The exchange of manuscripts, proofs and corrections between writer and publisher would take a lot longer than it would today, especially in the case of Wordsworth who is famous for his constant desire to revise his work, and that he lived far from the publishing centre of London. This letter came late in the preparation process as the Longman divide ledger shows that The River Duddon was published by the end of April.

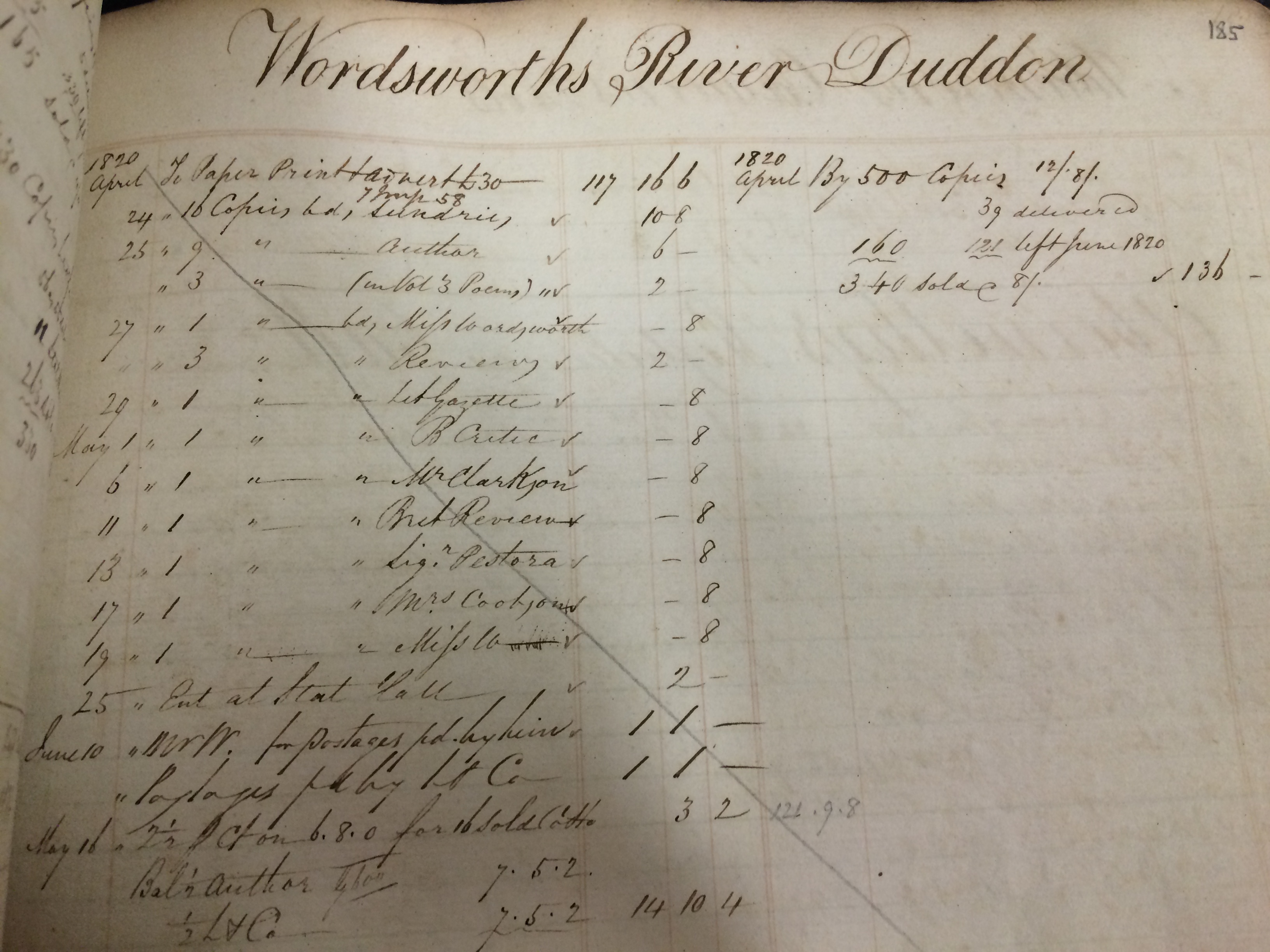

What’s wonderful about the context of this letter is that the publication history can be traced beyond the letter itself using the same archive. Much of Wordsworth’s poetry is celebrated for its quality, but did it sell?

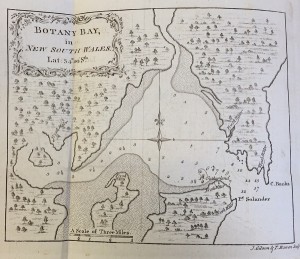

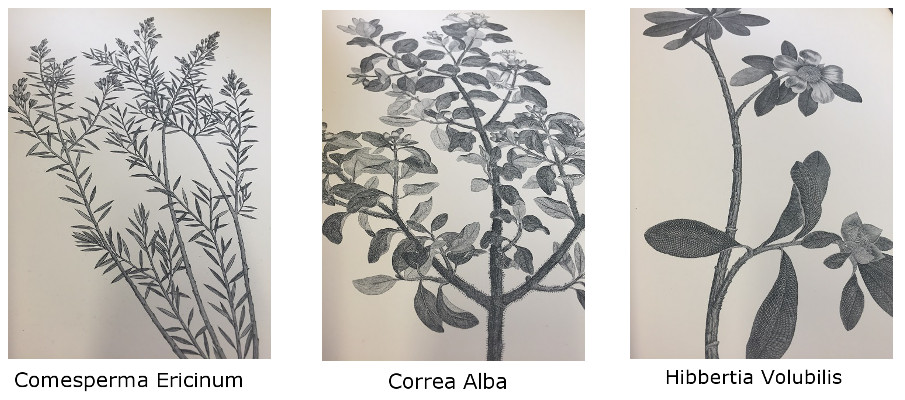

The River Duddon was printed in an edition of 500 copies and 14 years after it was first published there were 30 copies left unsold. These figures are roughly in line with Wordsworth’s previous volumes demonstrating a consistent but fairly low circulation among the reading public of the time. This changed as his popularity grew, and it’s interesting that the postscript of this letter (‘Announce in the Ad [for The River Duddon]: the Topographical description of the lakes’) refers to a work that would go on to outsell anything Wordsworth had written before. In 1810 he supplied a description of the Lake District to accompany a set of etchings by the Revd Joseph Wilkinson, however his name was not attributed to it. The River Duddon volume, therefore, was the first proper outing of the work fully credited to Wordsworth, but here it was still an addition to something else. When it was published separately for the first time in 1822 in an edition of 500 copies, it quickly sold out within the year and a second edition was published in 1823 amounting to 1000 copies which went on to sell out as well. This makes sense because the guidebook market in the early nineteenth century was saturated by guides to the Lake District which was fast becoming one of the places to travel to. Although Wordsworth seemingly added to a large market of literature on the subject, his Guide to the Lakes (as it became known) stands out above the rest in its unique approach to landscape. The majority of picturesque guidebooks at the time directed tourists to designated ‘stations’ where they could find a suitable viewpoint. Wordsworth’s Guide, written with an insider’s perceptive, considers the landscape as a whole and how people can be emotionally affected by nature.

Having researched and written about Wordsworth’s Guide whilst I was at university, it’s fascinating to see an early mention of it in such a peripheral manner. In fact, it’s rather nice to know that his handwriting, so familiar to me after my time in Grasmere, is just down the corridor.

You can find out more about the Longman Group Collection here, and how to access our archives here.