The Overstone Library was what we like to call the ‘foundation collection’ of the University Library. With nearly 8,000 printed volumes, mostly in the humanities and social sciences, it provides excellent research opportunities in economics, early pamphlets, travel, history, literature and classics, and political and religious philosophy. The emphasis is predominantly English and Scottish, and 18th century, with French works coming a strong second. .

The core of the Overstone Library was collected by John Ramsay McCulloch (1789-1864), the political economist. McCulloch began his collection at least as early as 1821, when he purchased pamphlets from the library of Rogers Ruding. On McCulloch’s death his library was bought by his friend and collaborator Samuel Jones Loyd, Baron Overstone (1796-1883), the banker. Baron Overstone added to it, and it remained at his seat Overstone Park in Northamptonshire until his daughter, Lady Wantage, bequeathed it to the University College Reading in 1920.

WM Childs wrote of the gift in his book Making a University (1933):

Childs wrote to Lady Wantage, who donated the collection, that it would strengthen us ‘just where every youthful institution is weak. A university must not be utilitarian and unromantic. Every visible record of notable events in the history of a place, every portrait, every inscription, every fine personal association, every beautiful garden, has a value far greater than most people imagine. I have always hoped that the library would be the crown of these things; the place where young students would feel, probably for the first time in their lives, the spell and dignity of learning. But that spell and dignity cannot be given by any number of merely useful books in buckram covers. The sober splendour of many cases of tall and finely bound and rare volumes is needful if a university library is to stir imagination and reverence as it ought to do.’

The collection is indeed full of finely bound and rare volumes, and should stir many imaginations. It is a fine example of a 19th-century private library, displaying a concern for good copies and the best editions, well printed and well bound. It contains good specimens of the Elzevirs, Barbou, Baskerville, Foulis, and Strawberry Hill presses, and 18th- and early 19th-century English and French bindings. Illustrated books include several Rudolph Ackermann publications and David Roberts’ The Holy Land (1842-1849) and Egypt and Nubia (1846-1849).

For more information or to find items, please visit the Overstone Library page on our website.

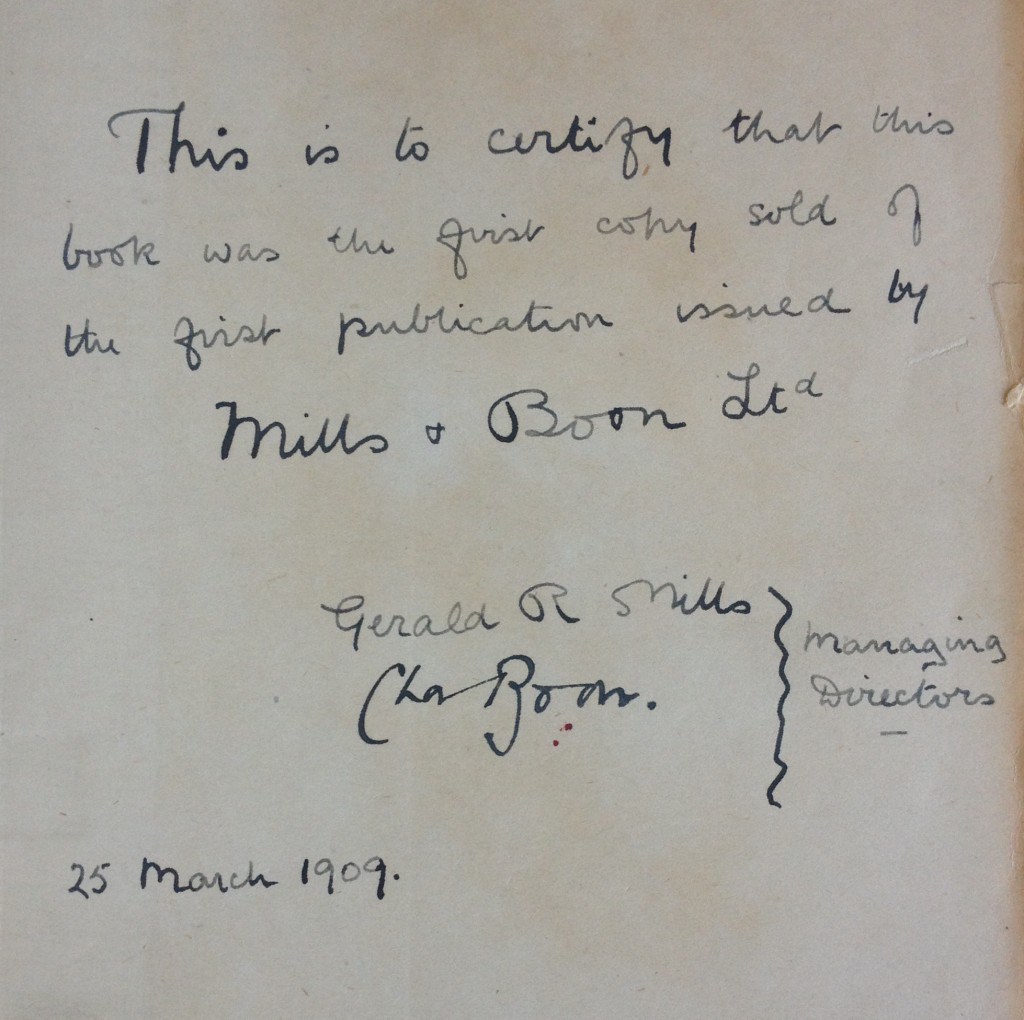

Although Mills & Boon didn’t start life as a romance publisher, the company’s first publication in 1908 was in fact a romance – Arrows from the Dark, by Sophie Cole.

Although Mills & Boon didn’t start life as a romance publisher, the company’s first publication in 1908 was in fact a romance – Arrows from the Dark, by Sophie Cole.