Written by Fiona Melhuish, UMASCS Librarian

Cover design for Leonard Smithers’ ‘Fifth Catalogue of Rare Books’ – from ‘A second book of fifty drawings’ by Aubrey Beardsley (1899). (RESERVE FOLIO–741.942-BEA)

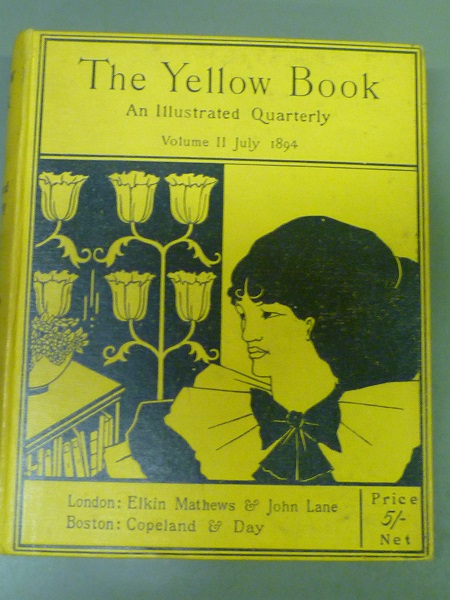

The art and literature of the 1890s is one of the strengths of the University’s Special Collections. However, although these holdings, along with the popular perception of the 1890s, tend to focus on male figures of the fin-de-siècle period, such as Oscar Wilde, Aubrey Beardsley and the publisher Charles Elkin Mathews, we also hold a number of early or first editions of publications by women writers of the 1890s. These works appeared in book form and also in short stories in avant-garde periodicals such as The Yellow Book and The Savoy (copies of both titles are held in our Reserve Collection).

This new writing was often daring, experimental and innovative, dealing with themes such as marital discontent, female sexuality and the literary and artistic aspirations of women. Their work shocked many contemporary critics, who labelled these ‘New Women’ writers as perverse and unnatural and ‘literary degenerates’, and part of the perceived cultural decline of the decadent period. These women writers were often mocked in the press, particularly in the pages of the satirical magazine, Punch, as shown in the cartoon below.

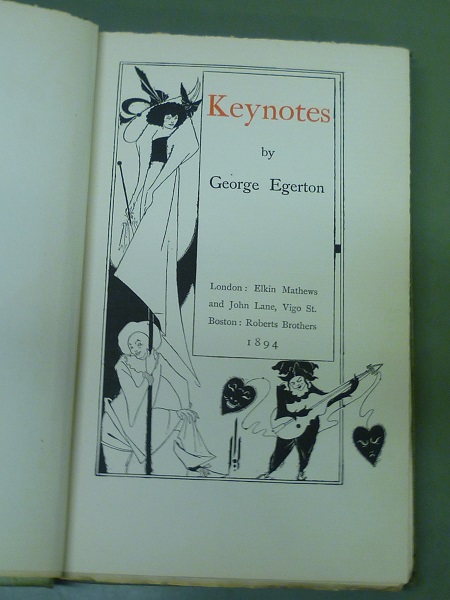

One of the key figures among the ‘New Women’ writers was George Egerton, pen name of Mary Chavelita Dunne (1859-1945) . A writer of short stories and plays, she was born in Australia, but was much travelled, living in Ireland, America and Norway before settling in London. Her subject was the lives of working-class women, and her writing was very popular when first published in the 1890s. Egerton’s volume of short stories, entitled Keynotes (1893) [see title-page below of the 1894 edition] was significant for its focus on female sexuality. A second volume, Discords, was published the following year (held in RESERVE–823.89-EGE). We also hold archive material relating to Egerton in the collection of papers of her friend, the poet, bibliographer and bibliophile John Gawsworth (MS 3547).

Title-page of ‘Keynotes’ by George Egerton (1894) with design by Aubrey Beardsley (ELKIN MATHEWS COLLECTION–EGE)

Sarah Grand (Frances Elizabeth Bellenden (Clarke) McFall) (1854-1943) was one of the most successful of the ‘New Women’ writers and left her husband in 1890 to pursue a career as an author. She is also thought to have coined the term ‘New Woman’ in 1894. Her first book to attract particular attention was The heavenly twins, published in 1893, which attacked double standards between the sexes ( we hold an 1894 edition). We also hold a first edition of her later work, Babs the impossible of 1901. (both at RESERVE–823.89-GRA)

We also hold the papers of Pearl Craigie (1867-1906) (MS 2133). Craigie was the author of a number of plays and novels under the pseudonym John Oliver Hobbes. She was President of the Society of Women Journalists in 1895, and also a member of the Anti-Suffrage League.

Women writers of the period were often overlooked as they often preferred to write short stories rather than full-length novels. The short story format offered move flexibility and freedom from traditional Victorian plots, which as the critic Elaine Showalter notes “invariably ended in the heroine’s marriage or her death. In contrast to the sprawling three-decker, the short story emphasised psychological intensity and formal innovation”.

The short story was seen by women writers as an opportunity to explore the psychology of women. As Egerton wrote: “I realised that in literature, everything had been better done by man than woman could hope to emulate. There was only one small plot left for her to tell: the terra incognita of herself, as she knew herself to be, not as man liked to imagine her – in a word, to give herself away, as man had given himself in his writings”.

Titles mentioned in this post are available to view on request in the Special Collections Service reading room.

References and further reading

Gawsworth, John. Ten contemporaries : notes toward their definitive bibliography. (London : Ernest Benn Ltd., [1932]). Reference copy held at Special Collections Service: MARK LONGMAN LIBRARY–016.82-GAW and copy held at the University Library: STORE–28802 (Includes ‘A keynote to “Keynotes” by George Egerton).

Heilmann, Ann. New woman strategies : Sarah Grand, Olive Schreiner, Mona Caird. (Manchester : Manchester University Press, 2004). Copy held at the University Library: 823.8-HEI/3rd Floor.

Krishnamurti, G. Women writers of the 1890’s. (London : Henry Sotheran Limited, 1991). Reference copy held at Special Collections Service: 820.99287-WOM and copy held at the University Library: 820.908-KRI/3rd Floor.

Showalter, Elaine (ed.) Daughters of decadence : women writers of the fin de siècle. (London : Virago, 1993). Copy held at the University Library: 808.8-DAU/3rd Floor.