Written by Louise Cowan, Trainee Liaison Librarian

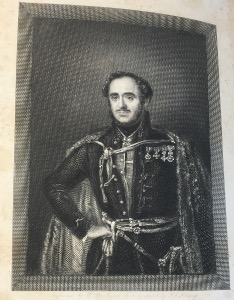

Born in Leicestershire in 1808, John Paget studied medicine at Edinburgh University before travelling extensively on the continent (Czigány). His travelogue, ‘Hungary and Transylvania: with remarks on their Condition, Social, Political and Economical’ published in 1839 was formed from his visits to the region during 1835-36 and was illustrated by George Hering, an artist who accompanied him on his journey.

The travelogue provides a plethora of careful insights, humorous accounts and details of historic interest. It is considered to be of great cultural importance and achieved particular prominence during the Hungarian War of independence in 1848-9 where it was consulted as a reliable source of background information on the country (Czigány). Indeed, Paget promises in his preface to the work to give an accurate picture of the countries he describes:

I know there are those who think, that “to write up a country,” a traveller should describe everything in its most favourable light; I am not of that opinion, -I do believe that a false impression can ever effect any lasting good.

And there is plenty of evidence that he held to his oath. He holds nothing back, for example, when describing the poor social behaviour of some guests at a dinner party in Presburg :

a well-polished floor, on which, I am sorry to say, I observed more than one of the guests very unceremoniously expectorate.

While Paget gives the usual details of landscapes and buildings, he is very much a natural storyteller. His writing is engaging, imaginative and beautifully descriptive; this passage evokes a sunset over the plains of Puszta–

It is just as the bright orb has disappeared below the level of the horizon; while yet some red tints, like glow-worm traces, mark the pathway he has followed; just when the busy hum of insects is hushed as by a charm…

Although he commended Hering for capturing “whatever might be distinctive, or curious, or beautiful,” on their journey, Paget’s writing is equally captivating – never more so than when he is recounting some of the myths and legends of the

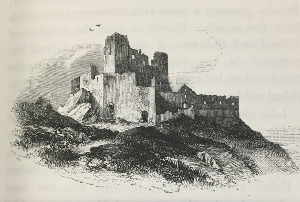

region (sadly, nothing to do with Vampires). For example, he recounts a gruesome true story on visiting Castle Csejta; describing the horrendous murders committed by Elizabeth Báthori in 1610. Believing that bathing in a maiden’s blood would grant her eternal life, “no less than three hundred maidens were sacrificed at the shrine of vanity and superstition” with Elizabeth luring them through a secret passageway from the castle to the cottage of her two accomplices.

Paget’s describes his encounters with the local people with equal animation, honesty and a little bit of sarcastic wit; such as the old man posing for Hering, who, “allowed a limb to be replaced in its former position, when accidentally moved [… ] though he did not seem to have the slightest idea of what was going on,” Or his

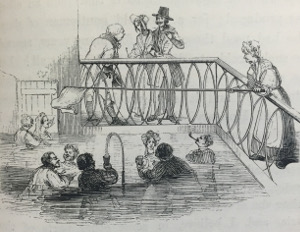

experience at the baths of Sliács, near Neusohl:

but conceive my horror, precise reader, when some very pretty ladies quietly informed me that they took their second bath in the evening and hoped I would join them!

(And join them he did, once he was properly supplied with an appropriate bathing-dress – “I do assure you delicate reader, that, as far as I could see, nothing occurred that could shock anyone.”)

Paget later married a Hungarian Baroness, Polyxena Wesselényi, the estranged wife of a Hungarian magnate, Baron László Bánffy, and lived with his family in Transylvania at Gyéres. He was granted Hungarian citizenship in 1847. Paget became a keen agriculturist and focused his efforts on improving his wife’s estate by applying new agricultural methods and using modern machinery: “A regular visitor to, and adjudicator at, international agricultural fairs, in 1878 he was awarded the Légion d’honneur at the World Exhibition in Paris,” (Czigány).

Sources and Further Reading:

Paget, J. (1839) Hungary and Transylvania. With remarks on their Condition, Social, Political and Economical. London: John Murray. [Available on request – Overstone 27A/13]

Lóránt Czigány, ‘Paget, John (1808–1892)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2008 [http://www.oxforddnb.com.idpproxy.reading.ac.uk/view/article/21115, accessed 17 Feb 2016]

![Lord Wolfenden's official University portrait. [UAC/10062, Brenda Bury 1963]](https://blogs.reading.ac.uk/special-collections/files/2016/02/wolfenden.png)

![Lord Wolfenden received letters from those less than impressed by the Report. [MS 5311/2/15]](https://blogs.reading.ac.uk/special-collections/files/2016/02/20160216_112730-1024x211.jpg)