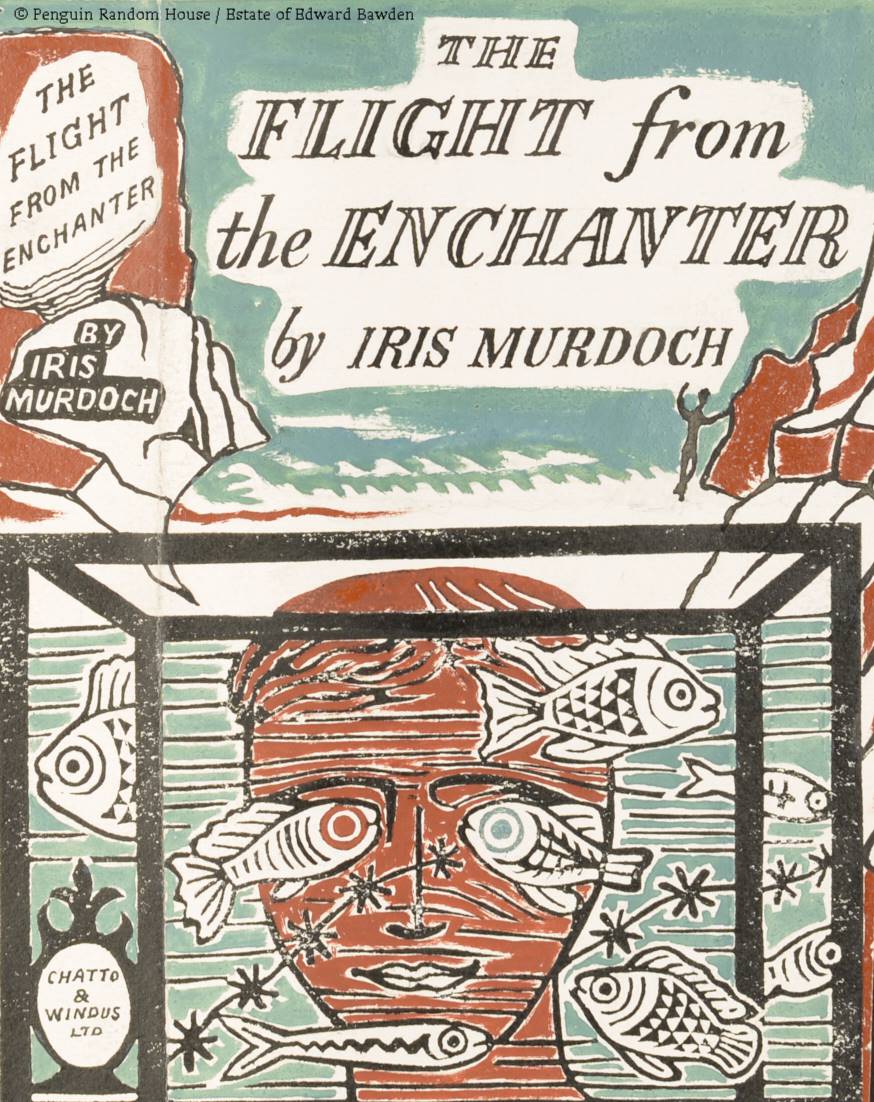

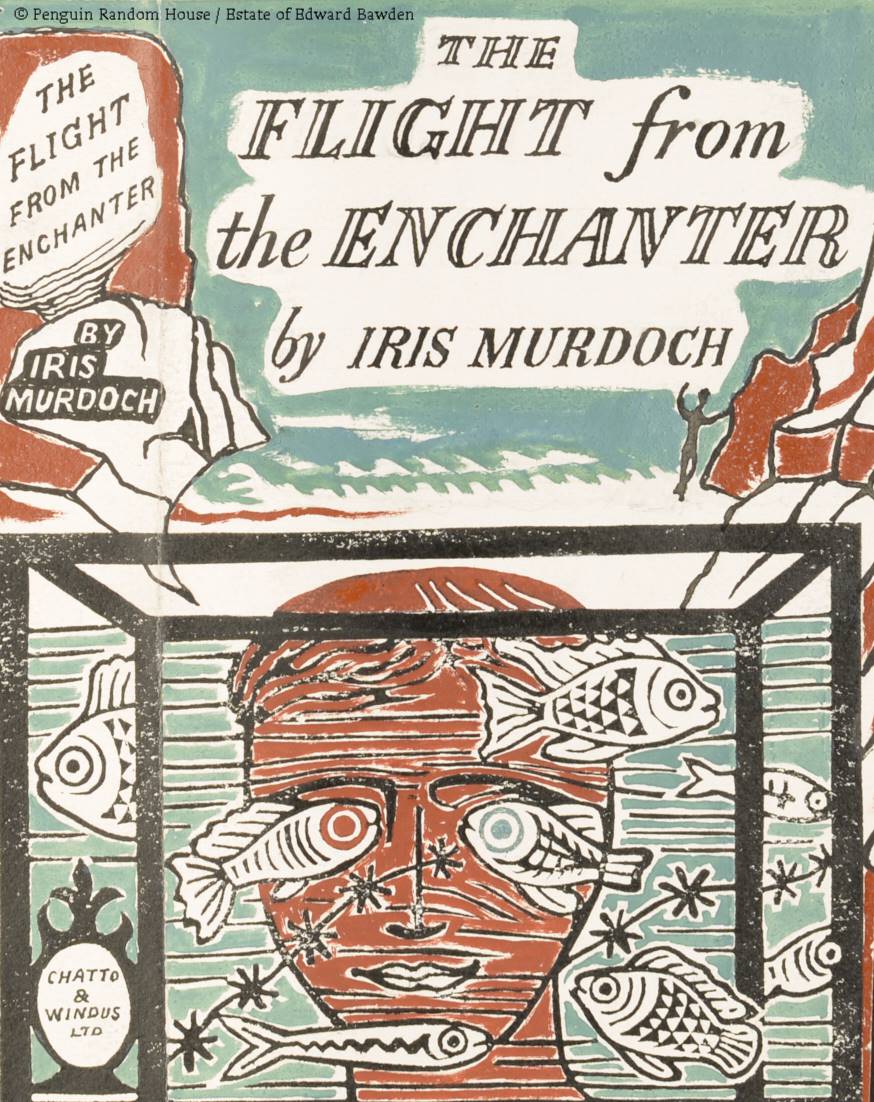

Edward Bawden’s cover design for The Flight from the Enchanter (Ref. CW AW/M/40).

The publishing archives of Chatto and Windus provide a fascinating insight into the process which brings a new book to its readers, allowing us to see the interplay between the literary and commercial worlds.

I decided to follow The Flight from the Enchanter, Iris Murdoch’s second novel, from the submission of the manuscript to the launch of the finished product to see this process in action.

‘By the Way, I Have a New Novel…’

Chatto and Windus maintained correspondence files concerning many of its published titles, containing letters to and from the author, the publisher and other relevant parties. The file for The Flight from the Enchanter (reference CW 548/2) tells us much about the creation of this novel.

Murdoch had already enjoyed considerable success with her debut Under the Net, published by Chatto and Windus in May 1954. Yet despite this achievement, she is casual on the subject of her next manuscript. Murdoch wrote to her contact at Chatto and Windus, Norah Smallwood (one of the company’s board members), on 5 May 1955. Although the letter mainly discusses her financial affairs (it seems most authors at some point write to their publishers asking for money), Murdoch waits until the final paragraph before revealing ‘By the way, I have a new novel…’ Smallwood’s reply, sent the following day, is enthusiastic: ‘I am plunged into the wildest excitement by your letter…. Of course I am dying to see the new novel’.

At this time, Murdoch was combining her literary career with her post as a lecturer in philosophy at St Anne’s College, University of Oxford. In her correspondence with Smallwood, Murdoch reveals something of the circumstances in which she was working. In a letter of 9 May 1955 she explains, ‘I’ll send the typescript shortly – I’d like to look through it again. Frenzied [with] philosophical papers just now’.

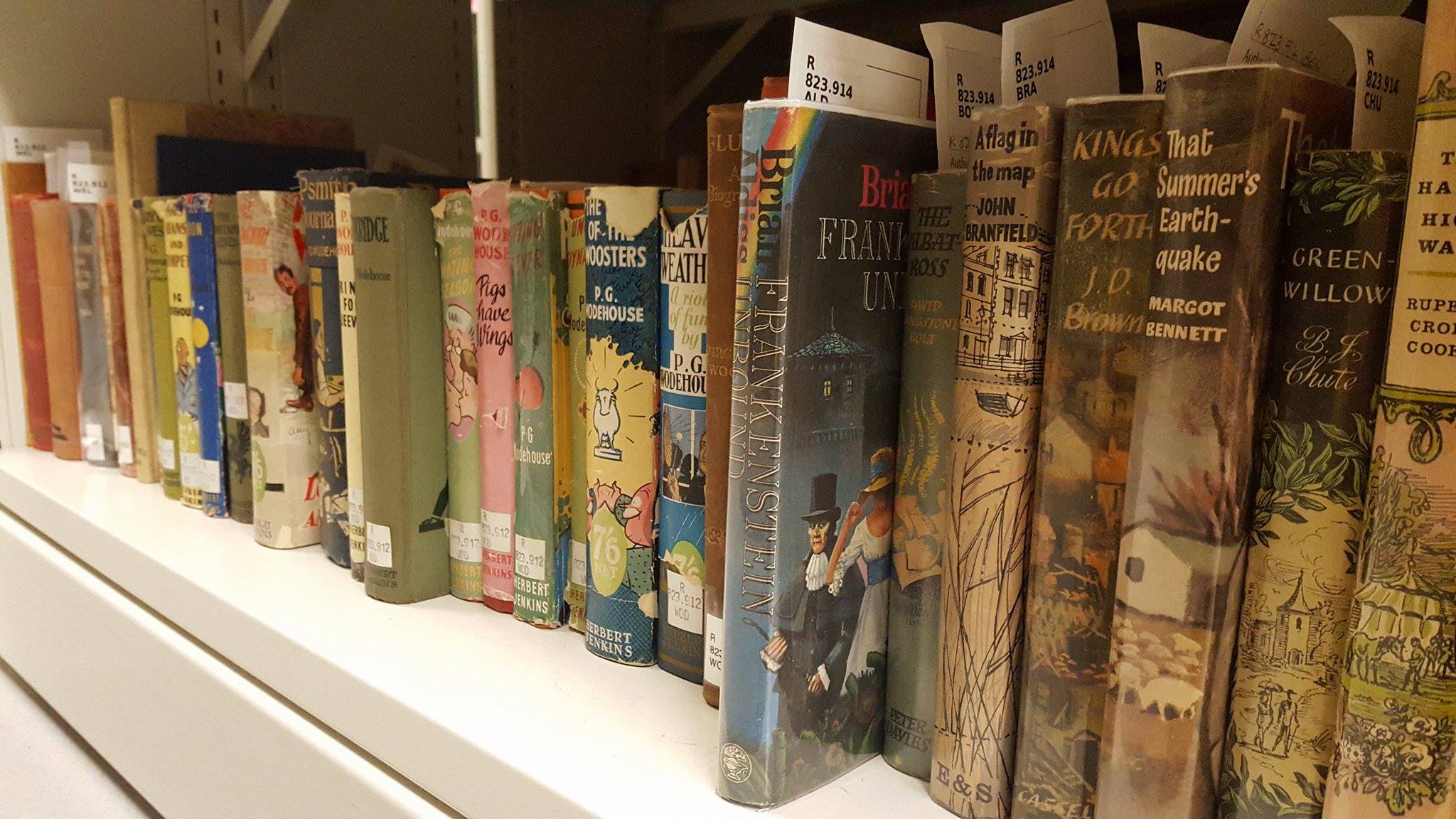

Final page of Reader’s Report no.12833, written by Cecil Day Lewis (Series Ref. CW RR).

The First Review

Chatto and Windus used Manuscript Entry Books to record all newly submitted manuscripts. Murdoch’s manuscript arrived on 23 May 1955 and was given to three readers for evaluation – Norah Smallwood herself, the then chairman Ian Parsons and the poet, Cecil Day Lewis. Chatto and Windus often used authors to appraise a new manuscript, indicating the significance of the literary perspective in their commercial decisions.

The resulting Reader’s Report written by Day Lewis himself (series reference CW RR) gives a mixed reaction. He begins, ‘This novel seems to me a whirl of scintillating fragments which never quite weave into a whole’. He goes on to find fault in so many aspects of the novel – some chapters drag, the plot construction is too loose and individual characters are merely ‘…bumping into one another, but giving no impression of relationship.’ There is little here to suggest that the novel will be a bestseller.

So why publish? Day Lewis sees merit in the writing, stating that ‘…some of the scenes are wildly funny [and] some excellently sinister…’ but his conclusion that ‘I don’t see that we can do much about this novel, except publish it!’ is hardly a resounding endorsement from Murdoch’s literary peer. Perhaps showing the sensitivity that publishers need in their relationships with authors, Smallwood’s letter of 13 Jun 1955 to Murdoch glosses over Day Lewis’ concerns, noting all reviewers had ‘….read it with very great enjoyment. It is exciting, sensitive, at times a little sinister and on many glorious occasions wildly funny.’ The letter also outlines the proposed terms of payments for the novel. Murdoch must have been greatly encouraged.

However, the same letter also makes the first suggestions for changes to the manuscript, starting the process of negotiated redrafting which characterises the relationship between publisher and author. The editorial correspondence for The Flight from the Enchanter (reference CW 548/2) shows that Murdoch was largely amenable to proposed changes, having previously been through this process for Under the Net. Nevertheless she is not lacking in resolve, especially to some of the more extensive edits suggested by Smallwood. In a letter of 2 Aug 1955, Murdoch refuses to remove one of the novel’s characters as suggested by Smallwood. The publishers, like Day Lewis, also had concerns about the series of accidental meetings between characters but Murdoch was insistent that they remain, stating that ‘They emphasise the dream-like, fairytale-like character of the book’. Manuscripts are evidently fertile ground for negotiation but Murdoch was clear on the boundaries, defending aspects that she considered integral to the text.

Producing the Finished Product

The collection contains a series of ledgers which record the costs incurred in producing a new publication. These include profit and loss figures and author’s accounts, as well as stock books which record printing details such as the numbers of units produced (series reference CW B/2). An initial run of 5,000 copies of The Flight from the Enchanter were printed on 16 Dec 1955, costing just over £238. Chatto and Windus were staking a sizeable amount of money on the title in the hope of making a profit. This initial run was noticeably larger than that of Murdoch’s debut, demonstrating her growing reputation as a novelist. Murdoch’s subsequent books would have increasingly larger first print runs as public interest grew in her work.

Press release sent to bookshops in January 1956 (from file CW 548/2).

Launch and Reaction

The Flight from the Enchanter was published on 23rd of March 1956 but publicity for the novel began well in advance. Stock book CW B/2/22 tells us that 75 copies of the novel were produced for publicity purposes which, along with the above press release, were sent out to various leading bookshops around Britain.

The collection of advertisement books (reference CW D) shows the investment Chatto and Windus put into The Flight from the Enchanter. These are scrapbooks with examples of the adverts placed in newspapers and magazines. Like today, the adverts often used favourable quotes from other authors. In the case of The Flight from the Enchanter, these included praise from the author VS Pritchett. This delighted both Smallwood and Murdoch. In a letter dated 8 Mar 1956, Smallwood tells her ‘His opinion will influence those wavering critics, of which there are, alas, so many nowadays, who are apprehensive about pronouncing their views too definitely.’ Again, the value of the literary perspective in the marketplace is acknowledged; the critical judgement of authors can be used to commercial advantage.

Chatto and Windus kept records of the critical response to their novels, adding small newspaper cuttings into a series of albums (reference CW C), and keeping longer articles in Review Files (reference number CW R). The Flight from the Enchanter received notably mixed reviews on its publication, something which Smallwood felt aggrieved by. In a letter of 9 Apr 1956 to the critic John Russell, Smallwood writes ‘To date the reviewers by and large have been chiefly concerned with condemning it for not being the book it isn’t.’ Smallwood’s belief in both the novel and the novelist is unwavering, but she must also have been concerned about sales and the impact that a commercial failure would have both on company profits and the morale of her author.

She should not have worried. The Flight from the Enchanter enhanced Murdoch’s reputation. She would go on to publish many more novels for Chatto and Windus until her death in 1999.

This is just one trail followed through the archives of Chatto and Windus. Their output was prodigious and diverse, and there are many more titles to be investigated.

Blog post written by David Plant (Project Archivist).

Sources and Further Reading

Chatto and Windus is one of several subsidiary companies of Penguin Random House. The University of Reading also maintains archives from other subsidiary companies under Random House, including The Bodley Head, Jonathan Cape, The Hogarth Press and John Lane. For more details of these collections, either use the online search function or visit the A-Z list of our collections. Both of these are available via our Special Collections homepage:

https://www.reading.ac.uk/special-collections/

Please note that researchers wishing to consult this collection are required to obtain permission prior to access. Please see the Archive of Random House publishers page for more information.

Cover Design © Penguin Random House / The Estate of Edward Bawden

Reader’s Report and Press Release © Penguin Random House