Written by Fiona Melhuish, UMASCS Librarian

Print of the Frost Fair of 1683 (This image is in the public domain via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AFrost_Fair_of_1683.JPG)

Behold the wonder of this present age,

A famous river now becomes a stage.

Question not what I now declare to you,

The Thames is now both fair and market too.

(Printed by M. Haly and J. Miller, 1684)

One of the memorable scenes from the film adaptation of Virginia Woolf’s novel, Orlando by the director Sally Potter, shows King James I and his courtiers looking down at an apple seller woman, frozen in a macabre yet beautiful tableau beneath the ice of the River Thames, her frozen apples appearing to float around her. I was reminded of this, and other evocative scenes from the film of the frozen Thames and a ‘frost fair’, when looking at a printed keepsake from the Thames frost fair of 1684 [see image below], one of the exhibits in our current Wintertide exhibition. For all the hardship caused by a severe winter, the idea of a frost fair, described by Woolf as “a carnival of the utmost brilliancy”, conjures up a romantic, magical image of a temporary (and precarious) world set upon the frozen river, a mini city which should not be there, and I was inspired to find out more.

A keepsake printed for a Mr John Warter at the frost fair on the Thames, 28 January 1684. From the collections of the Department of Typography and Graphic Communication (TYP CES MR/ Frost-fair/ 2 )

Over the centuries, a number of severe winters have resulted in the River Thames freezing solid, particularly in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries which became known as the Little Ice Age. This phenomenon attracted many visitors, and fairs and pageants were held on the ice, including what were to become known as frost fairs. The two most famous fairs took place during the winters of 1683/84, when the Thames froze for ten weeks and the ice reached a thickness of 11 inches, and 1739/40.The last large frost fair in the City of London took place in the winter of 1813/14.

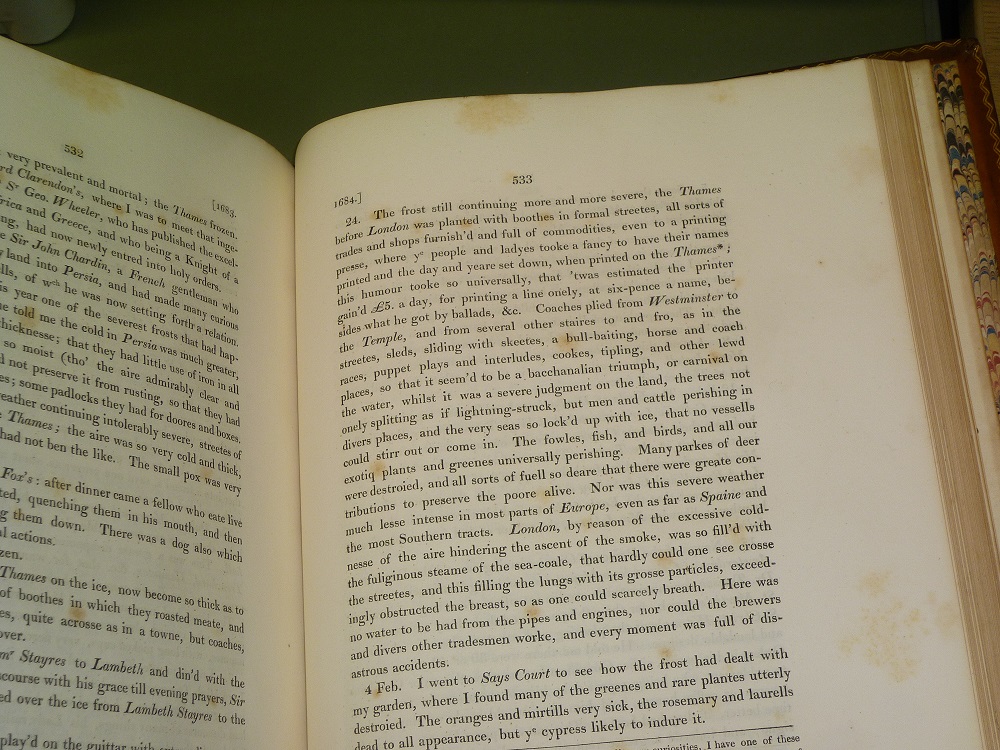

Pages from John Evelyn’s ‘Memoirs’ with several references to the severe frost and frost fair of 1683/4 (London, 1818. OVERSTONE–SHELF 36E/11 Vol. 1)

A number of contemporary accounts and prints, such as the one shown at the top of this post, were produced which describe or depict the fairs and their variety of stalls and entertainments in detail. In his description in his Memoirs of the fair of 1683/4 [see image above], the seventeenth century writer John Evelyn lists “sliding with skeetes, a bull-baiting, horse and coach races, puppet plays and interludes, cookes, tipling, and other lewd places” among the entertainments on offer – even a fox hunt took place on the ice. Stalls and booths were set up selling toys and books, fruit, beer and wine, and gingerbread, and oxen and sheep were roasted. Goods were often more expensive and exceeded their ‘dry land price’.

The fair of 1814 is recorded as being a lively and picturesque sight, the stalls a mass of fluttering, colourful flags, streamers and signs. Evelyn described the 1683/84 fair as a “a bacchanalian triumph, or carnival on the water”. However, as Woolf describes “it was at night that the carnival was at its merriest … the moon and stars blazed with the hard fixity of diamonds, and to the fine music of flute and trumpet the courtiers danced”. The stalls at night, teeming with noise, light and activity and the whirling and gliding of passing skaters, all illuminated by the moonlight on the sparkling ice, must have been an enchanting sight.

One of the most popular entertainments on the ice was to visit one of the many printing presses on the frozen river. According to Evelyn, “ye people and ladyes tooke a fancy to have their names printed and the day and yeare set down”, perhaps with a piece of verse, to create a ‘keepsake’ to commemorate the occasion of their visit:

To the Print-house go,

Where men the art of Printing soon do know,

Where for a Teaster, you may have your name

Printed, hereafter for to show the same:

And sure, in former Ages, ne’er ‘was found

A Press to print where men so oft were droun’d!

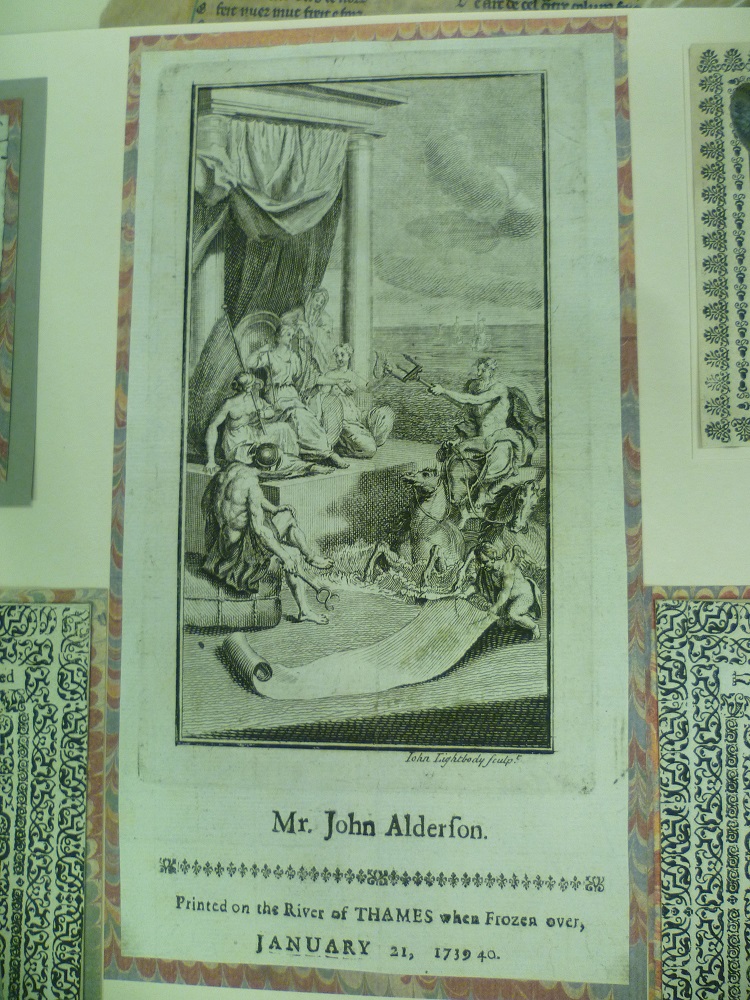

As well as the 1684 fair keepsake held in the Typography collections, we have also recently discovered a keepsake from the other famous Thames frost fair which took place in 1739/40 [see image below] in the John and Griselda Lewis Collection which we hold in Special Collections, and are in the process of cataloguing at present.

A keepsake printed for a Mr John Alderson, printed on 21 January 1740 at the frost fair on the Thames in 1739/40 (JOHN/GRISELDA LEWIS COLL–MS 5317/3/8)

Unsurprisingly, although the fairs were a source of much enjoyment, the severe winters caused a great deal of hardship, particularly for the watermen who depended on the river for their livelihoods, famine due to ruined harvests, damage to property and loss of life to many, and, as Evelyn reported, “the fowles, fish and birds, and all our exotiq plants and greenes [are] universally perishing”. Trees were split apart “as if lightning-struck”. The apple seller described by Virginia Woolf may have been inspired by Doll the Pippin woman who fell through the ice and died at the frost fair of 1715/16 and was the subject of a rhyme in Gay’s ‘Trivia’:

‘Pippins,’ she cries, but Death her voice confounds;

And pip, pip, pip, along the ice resounds.

The absence of a frozen Thames sufficient to hold a frost fair in the twentieth and twenty first centuries has not been due to a lack of severe winters, but other factors such as the growing size and heat of London and replacements for the London Bridge which have allowed freer flow of the river, changes which may have consigned the magical “carnivals on the water” to history.

The 1684 keepsake is available to view in our current staircase hall exhibition or by arrangement with the Department of Typography and Graphic Communication. The other two items are available to view by request in our Special Collections reading room.

The Wintertide exhibition, a celebration of winter traditions, customs and experiences, and the effects of the season on the natural world, is on display at the Special Collections Service from 8 December 2016 until 10 February 2017.

References and further reading

Ian Currie. Frosts, freezes and fairs : chronicles of the frozen Thames and harsh winters in Britain since 1000 AD. (Coulsdon : Frosted Earth, 1996). MERL LIBRARY–9639 CUR.