Last summer volunteer Jenny Knight began work on the mammoth task of transcribing the indexes to the letter books of outgoing correspondence in the Chatto & Windus publisher’s archive. The early letter books are an invaluable source of information as loose files of correspondence were sent for salvage during the First World War and most pre-1915 letters written to the firm are gone forever. The index work that Jenny and other staff and volunteers are doing is enhancing our catalogue records, benefiting staff and researchers using our database.

Read Jenny’s blog post to find out some of the things she’s discovered from these one-sided conversations, while deciphering 19th Century handwriting…

I was advised that the transcribing of the letter copies in the Chatto & Windus archive might be rather a dry and tedious business to volunteer to undertake. Slow, rather than tedious, might be true, but I have found it fascinating. The task is simply to record the name of the recipient and then the page numbers of the corresponding letters which the publisher had sent to them. The letter copies are handwritten, of course, on fragile tissue which requires care when turning the pages. The writing is beautiful copperplate, which unfortunately is sometimes quite difficult to read, so I frequently have to locate the individual letters to clarify and confirm the name. More often than not, I need to read some of the text too. I am discovering a snapshot of business life in the 1860s which is tantalizing; there are no records of replies to any of the letters, so there is room for conjecture as to the outcomes of the incidents mentioned, and on the background histories of the people who were communicating.

The first volume of letter records that I have been working on dates from the 1860s. The company was not called Chatto & Windus at that time; they were Saunders, Otley & Co. A couple of unexpected features (at least to me) are emerging. Firstly there is the international nature of the business, even as early as 1862. Letters were being sent to correspondents in America, particularly New York, to Australia and across Europe. In Europe there are a series of letters to Vienna and Paris – most intriguing are the letters to Versailles, where it seems a person at the very highest level of the French aristocracy was writing on dog breeding!

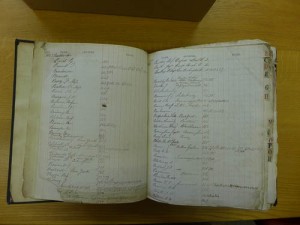

An example of a letter from Letter book 1, ref. CW A/1

An example of a letter from Letter book 1, ref. CW A/1

Secondly, it has become a cliché that women who made a living by writing were considered shocking and unacceptable in Victorian England; everyone remembers that the Brontes initially wrote under male pseudonyms. Yet here are numerous letters to and from potential and accepted women authors, all under their own names and with no suggestion that they should publish incognito. They are most certainly not in the majority, yet here they are, confounding expectations, and addressed with flowery Victorian politeness. A Miss Emily Thompson was advised that her novel “The Staff Surgeon” was not selling well. By February 1867 it had “not quite cleared expenses”. Poor Emily. I noted one instance, however, when the wife of a “Reverend”, i.e. a minister of the church, had items published. From the wording of a later letter in the sequence, it appears that a remuneration cheque was sent “care of” her husband, the minister, rather than directly to the lady herself. The details of the transaction cannot be known – but what a fascinating glimpse into the economic situation of women at the time.

Business practice in publishing seems to have changed little in the past hundred and fifty years. On a daily basis, potential authors are requested to amend and edit their texts, are advised that their manuscripts have not been considered suitable for publication, or that their book sales have been uneconomic and copies are being ”remaindered”. The luckier, more successful authors are sent payment. Debts are pursued with brisk and determined persistence. Lunches are arranged with colleagues in the trade. Here, too, is a mention of another company in publishing which was to become a household name – Saunders, Otley & Co were corresponding with W H Smith on a variety of topics; the relationship does not appear to have been without problems! Most amusingly, advertising accounts are paid in postage stamps, sent to local newspapers all over the country. What would modern publishers give for advertising accounts of 6 shillings (30p) to the Sheffield Times, 8 shillings (40p) to the Stockport Advertiser, or the highest sum of 10 shillings (50p) to The Scotsman? – I’m sure even the modern adjustment of these costs would still be very small to those in charge of 21st century advertising budgets!