Brian Ryder is one of our volunteers here at Special Collections. Brian’s history with Reading collections is a long one; he used to be one of our project cataloguers and is now working his way through the Routledge & Kegan Paul archive.

One hundred years ago, Sigmund Freud despaired of ever seeing published (as The Interpretation of Dreams) the English translation of his book Die Traumdeutung. His publishers, George Allen & Company, normally corresponded on this matter with translator AA Brill, an Austrian disciple of Freud’s living in the United States. However, in January 1913 they wrote directly to the author asking that various references to sexual matters be omitted, pleading that were this not to be done the book would have to be restricted in its sale only to those with a professional interest in its subject.

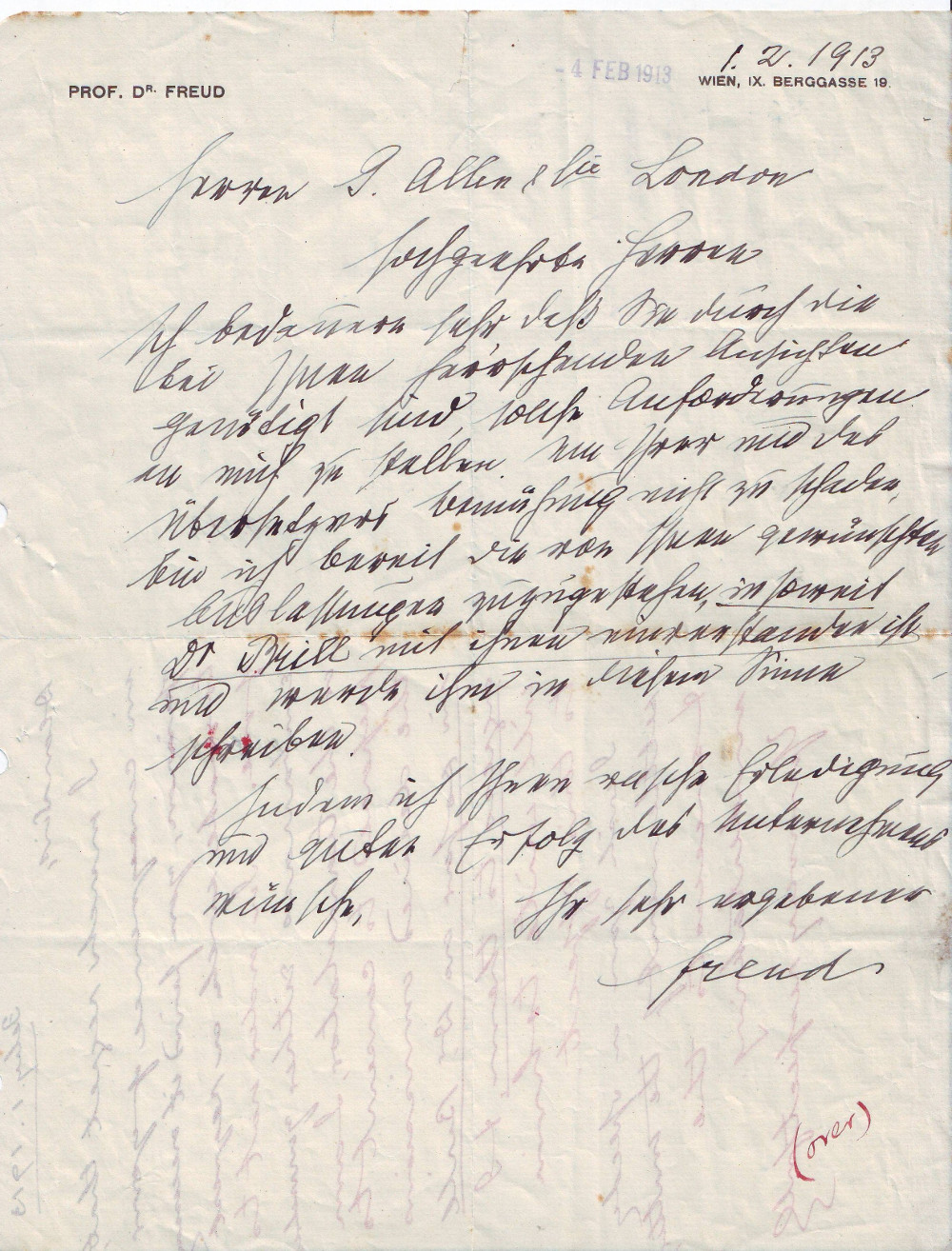

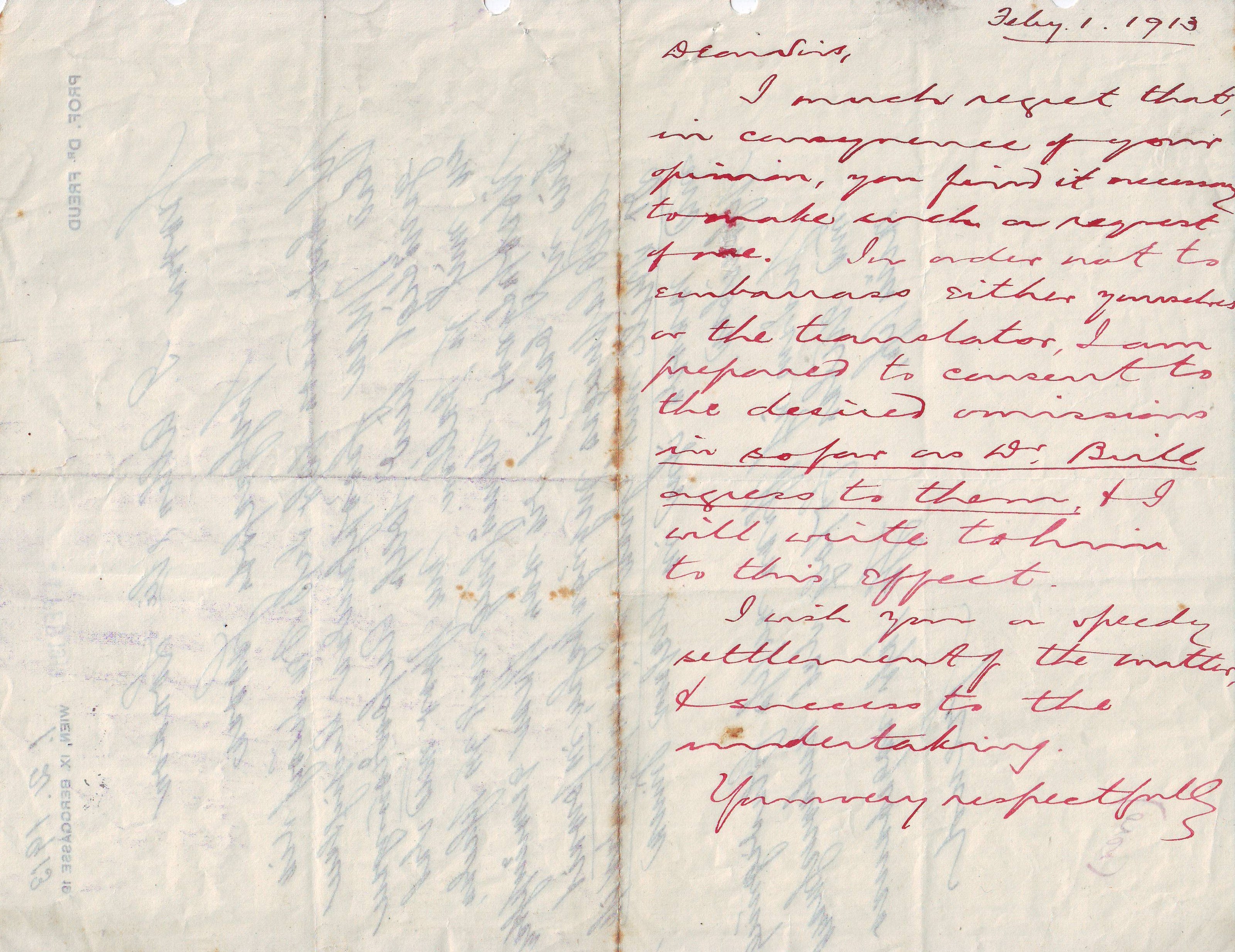

On 1 February 1913 Freud replied in German from Vienna (see AU C 2/13). Spencer Stallybrass, George Allen’s company secretary, translated the letter so that it could be considered by the editorial management. Stallybrass carefully folded the letter precisely in half and, in the hand which made the company’s board minutes so easily read and understood, wrote on the back the following:

Dear Sirs

I much regret that, in consequence of your opinion, you found it necessary to make such a request of me. In order not to embarrass either yourselves or the translator, I am prepared to consent to the desired omissions in so far as Dr Brill agrees to them, and I will write to him to this effect.

I wish you a speedy settlement of the matter, and success to the undertaking.

Yours respectfully

Freud

The book was immediately published and has been in print ever since. In 1914 George Allen & Company, unable to continue in business, was purchased from the receiver by Stanley Unwin and became George Allen & Unwin Ltd. Freud’s letter remained folded and unmentioned in any catalogue until it was discovered during preparations in 2000 for the Allen & Unwin archive to be made searchable online.

In 1929 Allen & Unwin published another book of interest to Freud and his circle, this time entitled A Young Girl’s Diary, anonymous but with an introduction by Freud. It was translated by Eden and Cedar Paul, favourites of Stanley Unwin who believed that no satisfactory translation could be completed which was other than into the translator’s first language (in the 1950s the translations of Freud’s work by Brill, for whom German was his first language, were replaced by new ones by James Strachey). A Young Girl’s Diary attracted the attentions of the Director of Public Prosecutions and the publisher was forced to do what George Allen had feared – booksellers who ordered it were instructed that it should only be sold to members of the medical, legal and educational professions (see AUC 5/15).