Written by Louise Cowan, Trainee Liaison Librarian

In honour of the return of much loved T.V. show ‘The Great British Bake Off’ we’ve pulled together some wonderful recipes and baking tips from our favourite 18th and 19th century cookbooks. Despite their popularity and the handy tips provided by the authors, I have to admit, some of these recipes seem trickier than a Bake-Off Technical Challenge but if you do brave tackling one or two, let us know how you get on!

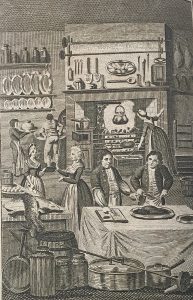

There are several things necessary to be particularly observed by the cook, in order that her labours and ingenuity under this head may be brought to their proper degree of perfection.

(Henderson, c.1800)

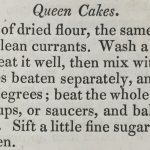

Cakes

The author of the following recipe, Maria Eliza Rundell, became a household name in cookery when she published, ‘A New System of Domestic Economy’ in the early 1800s. The title became an instant best seller, “with almost half a million copies sold by the time of Mrs Rundell’s death and remaining in print until 1886,” (Holt,1999).

Although this recipe suggests baking the cakes in tea-cups, Queen Cakes were often baked in a variety of shaped tins, one of the most popular shapes being that of the heart (Day, 2011).

Queen Cakes – (Rundell, 1822)

Mix a pound of dried flour, the same of sifted sugar, and of washed clean currants. Wash a pound of butter in rose-water, beat it well, then mix with it eight eggs, yolks and whites beaten separately, and put in the dry ingredients by degrees; beat the whole an hour; butter little tins, tea-cups, or saucers, and bake the batter in, filling only half. Sift a little fine sugar over just as you put it into the oven.

Biscuits

Our next recipe from Kettilby (1719) is the Ratafia Cake, a macaroon like biscuit that takes its name from the flavourings used. The word Ratafia, meaning liqueur, “came to denote almost any alcoholic and aromatic ‘water.’” (Boyle, 2011)

To make Ratafia-Cakes – (Kettilby, 1719)

Take eight ounces of Apricock-Kernels, or if they cannot be had, Bitter-Almonds will do as well, blanch them, and beat them very fine with a little Orange-Flower-Water, mix them with the Whites of three Eggs well beaten, and put to them two pounds of single-refin’d Sugar finely beaten and sifted; work all together, and ‘twill be like a Paste; then lay it in little round Bits on Tin-plates flower’d, set them in an Oven that is not too hot, and they will puff up and be soon baked.

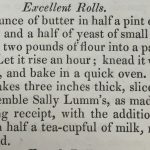

Bread

Maria Eliza Rundell suggests that her bread roll recipe is just as good as that found at Sally Lunn’s in Bath, which is quite the claim as Sally Lunn’s highly popular bun achieved legendary status in its day, (Sally Lunn’s, 2016). You can judge for yourself however, as Sally’s buns can still be enjoyed at her old house in Bath.

Excellent Rolls – (Rundell, 1822)

Warm one ounce of butter in half a pint of milk, put to it a spoonful and a half of yeast of small beer, and a little salt. Put two pounds of flour into a pan and mix in the above. Let it rise an hour; knead it well; make into seven rolls, and bake in a quick oven. If made in cakes three inches thick, sliced and buttered, they resemble Sally Lumm’s, as made at Bath. The foregoing receipt, with the addition of a little saffron boiled in half a tea-cupful of milk, makes them remarkably good.

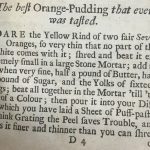

Desserts

In the preface to, ‘A Collection of above Three Hundred Receipts in Cookery, Physick and Surgery,’ Kettilby laments the unintelligible nature of many of the recipe books that came before hers, “some great Masters having given us Rules in that Art so strangely odd and fantastical, that it is hard to say, Whether the Reading has given more Sport and Diversion, or the Practice more Vexation and Chagrin, in spoiling us many a good dish, by following their directions.” Hopefully, her recipe for ‘the best orange pudding ever tasted’ will be a piece of cake to follow!

The best Orange-Pudding that ever was tasted – (Kettilby, 1719)

PARE the Yellow Rind of two fair Sevil- Oranges, so very thin that no part of the White comes with it; shred and beat it extremely small in a large Stone Mortar; add to it when very fine, half a pound of Butter, half a pound of Sugar, and the Yolks of sixteen Eggs; beat all together in the Mortar ‘till ‘tis all of a Colour; then pour it into your Dish in which you have laid a Sheet of Puff-paste. I think Grating the Peel saves Trouble, and does it finer and thinner than you can shred or beat it: But you must beat up the Butter and Sugar with it, and the Eggs with all, to mix them well.

Pastries

When it comes to tackling pastry, William Augustus Henderson had a number of great tips in his bestselling guide from the late 18th century, ‘The Housekeeper’s Instructor’, including how to avoid the dreaded ‘soggy bottom’:

One very material consideration must be, that the heat of the oven is duly proportioned to the nature of the article to be baked. Light paste requires a moderate oven; if it is too quick, the crust cannot rise, and will therefore be burned; and if too slow, it will be soddened, and want that delicate light brown it ought to have.

Once you’ve mastered the oven temperature you’ll be ready to bake this delicious treat:

Rasberry Tart – (Henderson, c.1800)

ROLL out some thin puff-paste, and lay it in a patty pan; then put in some rasberries, and strew over them some very fine sugar. Put on the lid, and bake it.- Then cut it open, and put in half a pint of cream, the yolks of two or three eggs well beaten, and a little sugar. Give it another heat in the oven, and it will be fit for use.

And finally, just in case you need to know how to get that thin puff-paste for your raspberry tart, here’s Maria Eliza Rundell to the rescue:

Rich Puff Paste – (Rundell, 1822)

Weigh an equal quantity of butter with as much fine flour as you judge necessary; mix a little of the former with the latter, and wet it with as little water as will make into a stiff paste. Roll it out, and put all the butter over it in slices, turn in the ends, and roll it thin: do this twice, and touch it no more than can be avoided. The butter may be added at twice; and to those who are not accustomed to make paste, it may be better to do so.

What makes these cookbooks particularly lovely is evidence that they were well used and well loved. The

Autograph inscription in ‘A Collection of above Three Hundred Receipts in Cookery, Physick and Surgery.’ Kettilby, 1719

autograph inscriptions hidden inside ‘The Housekeeper’s Instructor,’ (Henderson, c.1800) show it was a treasured family heirloom; given first to Helen Leachman by her Aunt Jane in 1879 then to Emma Leachman by her mother, June in 1825. Sophia Ann Leachman’s name also appears on top of the first page. Meanwhile ‘A Collection of above Three Hundred Receipts in Cookery, Physick and Surgery.’ (Kettilby, 1719) proved such a hit with Martha Kerricke, that she married the man who gifted it to her!

It’s lovely to see that baking and great recipes are things we continue to treasure and share- happy baking all!

Sources:

- Boyle, L. (2011) Ratafia Cakes. Janes Austen Centre. Available from: https://www.janeausten.co.uk/ratafia-cakes/

- Day, I. (2011) Queen Cakes and Cup Cakes. Food History Jottings. Available from: http://foodhistorjottings.blogspot.co.uk/2011/09/queen-cakes-and-cup-cakes-1.html

- Henderson, W. A. (c.1800) The Housekeeper’s Instructor; or Universal Family Cook. 10th London: J. Stratford [RESERVE–641.0942-HEN]

- Holt, G. (1999). Rundell, Maria 1745 – 1829. In L. Sage, G. Greer & E. Showalter (Eds.),The Cambridge guide to women’s writing in English. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from http://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/camgwwie/rundell_maria_1745_1829/0

- Kettilby, M (1719) A Collection of above Three Hundred Receipts in Cookery, Physick and Surgery. London; Richard Wilkin [RESERVE–641.5942-KET]

- Rundell, M. E. (1822) A New System of Domestic Cookery. New Edition. London: John Murray [RESERVE–641.0973-RUN]

- Sally Lunn’s (2016) Sally Lunn’s Historic Eating House. Available from: http://www.sallylunns.co.uk/history/

![Frontpieve from 'The Complete Gardener' by Thomas Mawe and John Abercrombie, 1854 [MERL LIBRARY RESERVE--4756-MAW]](https://blogs.reading.ac.uk/special-collections/files/2016/08/frontpiece-garden.jpg)