Written by Louise Cowan, Trainee Liaison Librarian

Edward Topsell, a Church of England clergyman, was born in Kent in 1572 and managed the parish of St Botolph in Aldersgate, London from 1604 until his death in 1625 (Lewis, 2004). Although he wrote several books, his most celebrated work is, ‘The History of Four-footed Beasts and Serpents’ (1607), a wonderful bestiary that describes all manner of creatures from Elephants to Bees to the Bear Ape Arctopithecus (or the three toed sloth as we know it today (University of Houston Library, 2013)). Each entry describes the creature in detail, giving commentary from ancient, medieval and contemporary sources. In particular, Topsell relied heavily on sixteenth century encyclopedia, ‘Historia Animalium’ by Conrad Gesner, reusing his work to the point where he could almost be accused of plagiarism (Lewis, 2004). This makes Topsell’s following claim a little dubious:

I cannot say that I have said all that can be written of these living creatures, yet I dare say I have wrote more than ever was before me written in any Language

However, even though he was not a naturalist by any means and borrowed much of this work from others, ‘A History of Four-footed Beats and Serpents’ remains a fascinating text. One of my favourite things about the beastiary is that includes not only the familiar and common animals but also the fantastical and frightening! Manticore, Satyr and Unicorn are all considered alongside cat and dog and horse and the descriptions provided are wonderfully detailed and perfectly illustrated.

Below are some of my favourite mythical monsters from the book:

Of the Mantichora

A terrifying monster residing in India that has earned the fearsome title of ‘man eater’, the Manticore is described by Topsell as a deadly combination of man, lion and scorpion:

a treble row of teeth beneath and above, whose greatness, roughness, and feet are like a lyons, his face and ears unto a mans, his eyes grey, and colour red, his tail like the tail of a Scorpion, of the earth, armed with a sting, casting forth sharp pointed quils; his voice like the voice of a small Trumpet or Pipe, being in course as swift as a Hart; his wildness such as can never be tamed, and his appetite is especially to the flesh of man.

The manticore uses its tail to attack hunters and prey and is able to grow back any quills lost in the fight.

Of the Lamia

Topsell initially describes what he believes to be the fabled accounts of the Lamia, which show her as a ‘phary’ (fairy) or shape-changer who wishes to steal away children and tempt beautiful men. As such creatures do not exist in the Bible, these tales originated, according to Topsell, from poets who use the term Lamia as an allegory for a harlot.

The true Lamia, instead hails from Libya and is known in Hebrew as the creature ‘Lilith’. It is described as:

having a womans face, and very beautiful, also very large and comely shapes of their breasts, such as cannot be counterfeited by the art of any Painter, having a very excellent colour in their fore-parts without wings, and no other voice but hissing like dragons.

The Lamia is said to enchant men with its body before overthrowing and devouring them.

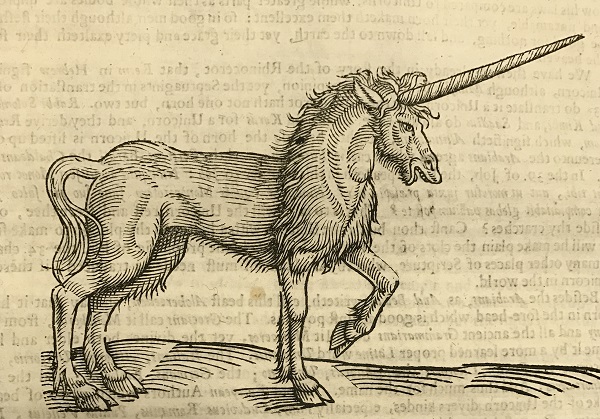

Of the Unicorn

Although Topsell consults many ancient sources, he finds their accounts of the descriptions of Unicorns so divergent that he can only assume there are many varying kinds of the creature, much as there are types of dog or mice. However, he confirms that they can be found in both India and Ethiopia, that they have a single horn in the middle of the forehead, are roughly the size of a horse, and tend toward a solitary life.

Of course the most fascinating part of a Unicorn is its horn and Topsell recounts an interesting story from the life of Apollonius of Tyana by Philostratus:

the Indians of that horn make pots, affirming that whosoever drinketh in one of those pots, shall never take disease that day, and if they be wounded, shall feel no pain, or safely pass through the fire without burning, nor yet be poisoned in their drinks, and therefore such cups are only in the possession of their Kings.

Although Apollonius discounted some of the effects of the Unicorn horn, he seemed to accept that it may have some medicinal properties.

Of the Dragon

Like Unicorns, dragons are also said to be bred in India and Africa and are diverse in size and colour. The dragon illustrated above is the Winged Dragon whose wings are described as being of “a skinny substance, and very voluble, and spreading themselves wide, according to the quantity and largenesse of the Dragons body.”

More generally, dragons are beautiful to behold, despite their terrifying treble rows of teeth. They have bright and clear seeing eyes, “dewlaps growing under their chin and hanging down like a beard[…] and their bodies are set all over with very sharp scales, and over their eyes stand certain flexible eye-lids.”

They also have very keen senses of seeing and hearing, making them the perfect watchful keepers of treasure and unmarried maidens.

According to Topsell (affirmed by Aristotle), dragons are specifically offended by eating apples and lettice and will eat the latter to vomit up any meat they find does not settle well in their stomachs!

To kill a dragon, Topsell recounts that Indians will,

take a garment of Scarlet, and picture upon it a charm in golden letters, this they lay upon the mouth of the Dragon’s den, for with the red colour and the gold, the eyes of the Dragon are overcome, and he falleth asleep, the Indians in the mean season watching and muttering secretly words of Incantation; when they perceive he is fast asleep, suddenly they strike off his neck with an Ax

Our edition of ‘The History of Four-Footed Beasts and Serpents’ is a later revised version to which is attached the ‘Theatre of Insects’ by T. Muffet. Lewis (2004) suggests that Topsell had originally intended to produce his own third and four volumes on birds and fishes but these unfortunately were never completed.