A few times a year, the archives and library team ventures out to visit another library, archive, museum or similar. Last week’s visit was to Douai Abbey in Upper Woolhampton, Berkshire. Library staff member Helen Westhrop reports…

Tolle Lege (Take up and read)

This week a group of us in Special Collections went on a busman’s holiday. We visited the library and archives at Douai Abbey. Fortunately it is only a few miles away so were had no difficulty ensuring our own collections we left in good care for two or three hours.

The library and archive building was designed by David Richmond and opened in 2010 by Rowan Williams who was at that time the Archbishop of Canterbury.

It is built on the site originally designated for the library by Sir Frederick Gibberd as part of his larger plan for the monastery in 1964. Today’s building houses various library and archive collections, notably from the monastic community’s own earlier libraries in Paris (from 1615) and Douai (from 1818) in France and Woolhampton (from 1903). At present, the library holds approximately 100,000 items.

Beside the path leading to the library building is a long bed of lavender and the brick work we noticed is in the form of books on shelves. The gothic-tracery window frame by the visitors’ entrance was rescued from the former Douai School after it closed.

The main entrance leads straight into the reading room with some small rooms leading off where a number of reference works are housed. Through a window to east is a rockery and pond built in the 1930s. On the wall are sculpted heads from the medieval Reading Abbey. The other walls are lined with portraits of professors and patrons of the University of Douai and the English College in northern France. There are also portraits of the prioress of the English Carmelite community founded in Antwerp and of the English Augustinian canonesses founded in Louvain, Belgium.

On the shelves in the reading room are the theological and liturgical collection, and the rest are in mobile shelving in a room nearby. There are also some framed examples of medieval manuscripts on the wall beside and nearby some more portraits of English Benedictines, mainly Douai monks.

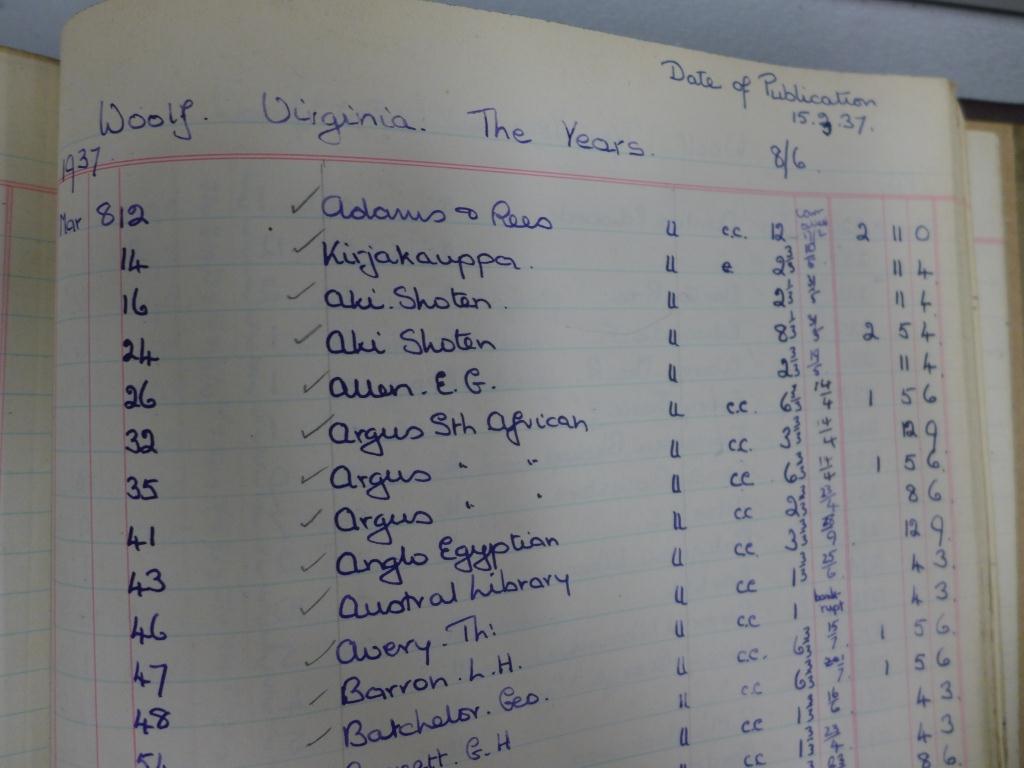

The librarian showed us the archives room, which is restricted and contains archives and artefacts from a variety of other religious congregations and monastic communities. Here we saw some of the beautifully embroidered Wintour vestments, previously owned by a family involved with the Gunpowder Plot. The collection was split up some time ago, but an exhibition is planned so that they all can be viewed together.

Before looking at some other items from the store we ventured upstairs to a pulpit-shaped landing and the librarian’s office. Nearby is the utility room that houses the equipment for the ground-source heating that provides the stable atmosphere for the conservation of books and archives.

It was an interesting library in the most beautiful surrounding – well worth a return visit.