Beware! A warning – to Suffragists (1908?) by Cicely Hamilton. Stenton Collection.

Bethan Davies is our outgoing Academic Liaison Support Librarian. In this blog, she speaks about sixteen books within the Stenton Collection, and identifying their former owner, C.E. Hodge.

The beginnings of this story start with the various celebrations to mark #Vote100, the centenary of the Representation of the People Act which allowed (some) women the right to vote. My role based in Special Collections includes managing our social media and blog content, and at the time, I was looking through our collections to find items related to women’s suffrage.

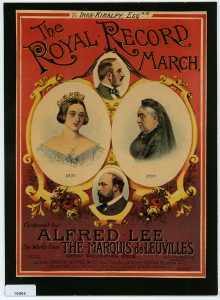

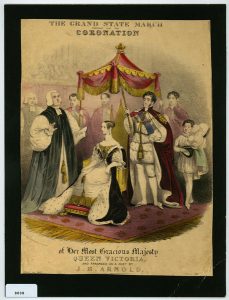

In this situation, I was quite spoilt for choice. A key collection within our archives are the Nancy Astor papers, which have been the focal point in Dr. Jacqui Turner’s research, and further explored in this year’s #Astor100 campaign. We hold the archives and collections of several female authors and artists, including the first female professor in Britain and suffragette Edith Morley. On the other side of the debate, we have Pearl Craige, who was a member of the Anti-Suffragette League. Three of the covers from our Spellman Collection of Victorian Music Hall Covers clearly depict the growing anxiety of the feminist movement. But our story is focused not on the archives, or music hall covers, but on the shelves of the Stenton Library.

The Stenton Library is the combined academic collections of Sir Frank and Lady Doris Parsons Stenton. Sir Frank was a Professor of Modern History and former Vice-Chancellor of the University of Reading. His wife, Doris Parsons Stenton also worked at the University as a Reader and then Lecturer in History. Both Frank and Doris were medievalists and the Library reflects this interest. (We also hold their personal Papers and the Stenton Coin Collection which goes all the way back to King Offa of Mercia.)

However, the Library also reflects the Stenton’s broader interests, including women’s history. One of Doris’ works was The English Woman in History (1957), and several of these titles are included in Elizabeth James’ Checklist of Doris Stenton’s books (1988). There are entire shelves dedicated to feminism, women in the workplace, and prominent authors such as Mary Wollstonecraft, Hannah More, and Elizabeth Fry. There are also several titles related to suffrage movement, such as this wonderful illustrated pamphlet satirising anti-suffragette propaganda, written by Cicely Hamilton.

It was whilst looking through these titles that I noticed something. About four books I had looked at were focused on key figures, or the overall history of the fight for women’s right to vote (autobiographies or biographies of Annie Kenney, Millicent Garrett Fawcett, Cicely Hamilton and Ray Strachey’s History of the Women’s Movement). All had the name “C.E. Hodge” in the front.

The study of provenance (the origin or early history of a book), is a key aspect of the study of the history of the book, particularly in connection to ownership, marginalia, and how early readers interacted with their books. Special Collections librarians will often try to include any marks of ownership in books in catalogue records, such as bookplates, binding detail or autographs. This can sometimes lead to moments of great excitement – such as when I held a book which had previously been owned by Mary Shelley , or my colleague who recently found a book presented to the University of Reading Library by Thomas Hardy. In this case, however, C.E. Hodge did not ring any bells with me. I put it down to being an interesting quirk and moved on.

A few months later, I was looking up some more works this time related to women’s medical history. Again this is a topic we hold a variety of items on, especially within the Cole Collection. Margaret Sanger’s autobiography came up, also in the Stenton Collection. Our online catalogue mentioned an “Autograph inscription : C. E. Hodge”. Indeed, it is only because one of my former colleagues had taken notice and catalogued this information, that I was able to take my research any further. Intrigued, I clicked on the author heading for “C.E. Hodge” within our online Catalogue. The catalogue showed that 16 titles, all within the Stenton Collection, all related to women’s history, suffrage or anti-suffrage movements, and women in the workplace, all formerly owned by C.E. Hodge. Only one, Annie Besant’s autobiography, includes the date 9.9.36 next to Hodge’s name (full list of titles below).

This immediately set me off to do further research. Google and Wikipedia, however, let me down. No name sprang up for “C.E. Hodge” except for several businesses and some family history pages. A search “C.E. Hodge AND Medieval” came up with several Google Book references for a PhD thesis from the University of Manchester on ‘The Abbey of St Albans under John of Whethamstede’ by C.E. Hodge, but nothing further. No other variance of search terms seemed to provide any further clues.

Who was C.E. Hodge? Was he/she involved in the suffrage movement in some way? Did they know the Stentons? And how were their books now in our Stenton Collection?

- C.E. Hodge’s autograph.

- The titles owned by C.E. Hodge.

A few months passed. Christmas came and went.

I had asked a few questions about C.E. Hodge to my colleagues within Special Collections, which had not revealed a huge amount. The Stenton Papers make no reference to anyone by the name of Hodge. The accession papers, which document how the collection came to Special Collections, made no reference to the provenance of any of the titles, beyond their donation by Lady Doris, and discussions regarding furniture. Later additions had been added to the collection by librarian Hazel Mews, but none of the sixteen books were among these items. Elizabeth James’ Checklist only showed that the books were considered part of Doris Stenton’s Library. I even delved into the Card Catalogue, which, apart from making me feel very old-school and fancy, didn’t give me any further clues.

I did not think I would get any further with this search, and as I was going to be starting a new job soon, my chances of doing any further searches were dwindling. I therefore decided to take a different tack.

I decided to try the Library Hub Discover (formerly COPAC) in order to see if there were any more works with the autograph inscription C.E. Hodge. The Library Hub searches across the library catalogues of hundreds of the major UK and Irish libraries, including academic, research and specialist libraries. I wanted to do this in case other collections had Hodge’s work, and whether they had any further information upon who Hodge was. The search came up with the sixteen titles from our collection only. Taking it one step further, I then clicked on the author heading C.E. Hodge, to bring up any further works associated with the name.

This time the search returned the 16 original books, the Manchester PHD thesis, and three new titles. A journal called Women Speaking, an article on the Women’s International Quarterly and a book titled A woman-orientated woman /. All three were under the name C. Esther Hodge.

Esther Hodge (1908-1994) was a history graduate from the University of Manchester, and secondary school teacher. She became editor for Women Speaking, worked for the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom and chaired the Open Door International for the Economic Emancipation of the Woman Worker. Her autobiography “A woman-orientated woman” documented her experiences as a lesbian, and is often quoted or referred to in works on lesbian history. Her papers are held at LSE and Bristol.

I have contacted both archive collections, and LSE kindly sent me back an image of Hodge’s signature. At first glance, it’s obvious that the signature is hers – especially in relation to the small d. It would make sense for someone with Hodge’s interests to own, or have read the sixteen titles on women’s work and women’s history. The autobiography of Margaret Haig Thomas, 2nd Viscountess Rhondda, is particuarly interesting as she was the founder of the Six Point Group, which Hodge would later work with. I’ve not been able to visit either collection yet, but I am hoping to do so in the future.

There are still, however, some unanswered questions. How did the books end up with the Stentons? Hodge spent a year in Australia, which might be why she wanted to sell some of her titles – and it is intriguing that the titles are all from the 1890-1930 period and focused on similar topics. The medieval history background seems the most obvious link – could Hodge have known either of the Stentons? Doris Stenton seems the obvious choice, but we cannot rule out that her connection was with Frank instead. Or was it just a fluke that the Stenton’s happened to purchase Hodge’s titles together?

Some of these questions may never be answered. Some may come to light in future discoveries. What I think is key here is that this discovery could not have happened without the dedicated cataloguing by our librarians, the work of JISC and the archival collections of LSE and Bristol. I hope my small find helps and inspires those interested in these topics to look further into the Stentons’ connection to Esther Hodge, or to consider further the role of ownership. The titles that we hold in libraries are not only special because of their authors, but how they inspired and influenced the readers who interacted with them. The study of provenance is not only important within the history of the book, but in the studies of historiography and the discussion of ideas. I have been very lucky to work with the Special Collections, and even now, the collections still surprise me with the wonderful treasures they hold.

If you have any further information on Esther Hodge, or would like to view these items, contact us at specialcollections@reading.ac.uk.

Full list of the titles owned by Esther Hodge within the Stenton Collection (also available to view in our Library catalogue)

Women and politics (1931) by the Duchess of Atholl. STENTON LIBRARY–BD/04

Annie Besant: an autobiography (1893) STENTON LIBRARY–BB/05

Our mothers : a cavalcade in pictures, quotation and description of late Victorian women, 1870-1900 (1932) edited by Alan Bott ; text by Irene Clephane. STENTON LIBRARY–BB/09

Life errant (1935) by Cicely Hamilton STENTON LIBRARY–BB/24

Memories of a militant (1924) by Annie Kenney. STENTON LIBRARY–BB/11

Margaret Ethel MacDonald (1912) by J. Ramsay MacDonald. STENTON LIBRARY–BB/03

This was my world (1933) by Viscountess Rhondda. STENTON LIBRARY–BB/15

Margaret McMillan: prophet and pioneer (1932) by Albert Mansbridge. STENTON LIBRARY–BD/03

Women as army surgeons : being the history of the Women’s Hospital Corps in Paris, Wimereux and Endell Street, September 1914 – October 1919 (1920) by Flora Murray. STENTON LIBRARY–BB/10

My fight for birth control (1932) by Margaret Sanger. STENTON LIBRARY–BC/04

Nine women, drawn from the epoch of the French revolution (1932) by Halina Sokolnikova (Serebriakova) ; translated by H. C. Stevens ; with an introduction by Mrs. Sidney Webb. STENTON LIBRARY–BB/04

Unfinished adventure : selected reminiscences from an Englishwoman’s life (1933) by Evelyn Sharp. STENTON LIBRARY–BC/05

Hertha Ayrton, 1854-1923 : a memoir (1926) Evelyn Sharp. STENTON LIBRARY–BC/06

Impressions that remained : memoirs (1919) by Ethel Smyth. STENTON LIBRARY–BB/20 VOL. 1-2

Millicent Garrett Fawcett (1931) by Ray Strachey. STENTON LIBRARY–BC/24

The cause : a short history of the women’s movement in Great Britain (1928) by Ray Strachey. STENTON LIBRARY–BD/05

correspondence, ledgers & miscellaneous records from 1813–1976. The

correspondence, ledgers & miscellaneous records from 1813–1976. The