Written by Louise Cowan, Trainee Liaison Librarian

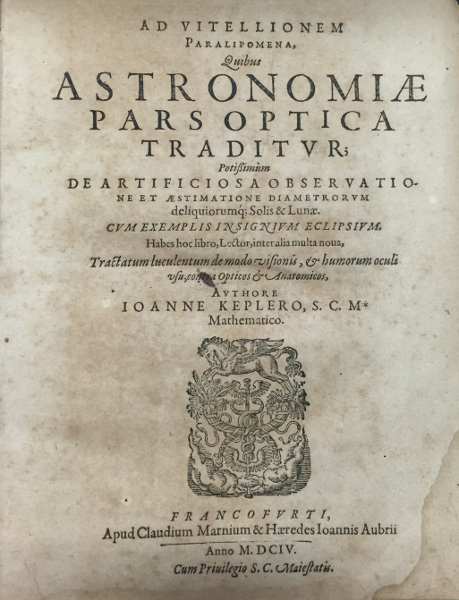

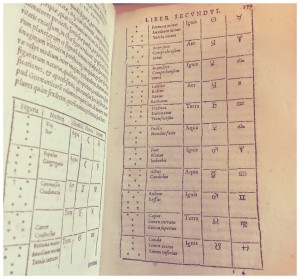

The theme of this year’s Science Week taking place from 11-20 March is ‘Science in Spaces’ so to celebrate here is our first edition of ‘Ad Vitellionem Paralipomena, Quibus Astronomiae Pars Optica Traditur’ (Supplement to Witelo, in Which Is Expounded the Optical Part of Astronomy) by German astronomer Johannes Kepler.

Born in 1571, Kepler was a leading figure during the scientific revolution of the 17th Century. While usually best known for his discovery of three major laws of planetary motion, which “turned Nicolaus Copernicus’s Sun-centred system into a dynamic universe, with the Sun actively pushing the planets around in noncircular orbits,” (Britannica Academic, 2016) his work on optics was equally ground-breaking and earned him the title ‘father of modern optical study,’ (Skydel and Whelan).

Copernicus’s Sun-centred system into a dynamic universe, with the Sun actively pushing the planets around in noncircular orbits,” (Britannica Academic, 2016) his work on optics was equally ground-breaking and earned him the title ‘father of modern optical study,’ (Skydel and Whelan).

Written in 1604, ‘Astronomiae Pars Optica’ explores the properties of light, applying the ideas of reflection and refraction to explain astronomical phenomena, such as the size of astronomical bodies and the nature of eclipses. It also investigates the workings of light with regard to pinhole cameras and the human eye. In his explanation of vision, Kepler was the first to recognise the importance of the retina and the inversion of images within the eye, and the first to explain how eyeglasses, in use for over three centuries, actually worked, (Britannica Academic, 2016). Kepler’s understanding  of light and vision later allowed him to invent the Keplerian telescope in 1611; by replacing the concave eyepiece used by Galileo with a convex lens, Kepler was able to make considerable improvement to the design; although this inverted the image produced, it enabled a much wider field of view, (Di Liscia, 2015).

of light and vision later allowed him to invent the Keplerian telescope in 1611; by replacing the concave eyepiece used by Galileo with a convex lens, Kepler was able to make considerable improvement to the design; although this inverted the image produced, it enabled a much wider field of view, (Di Liscia, 2015).

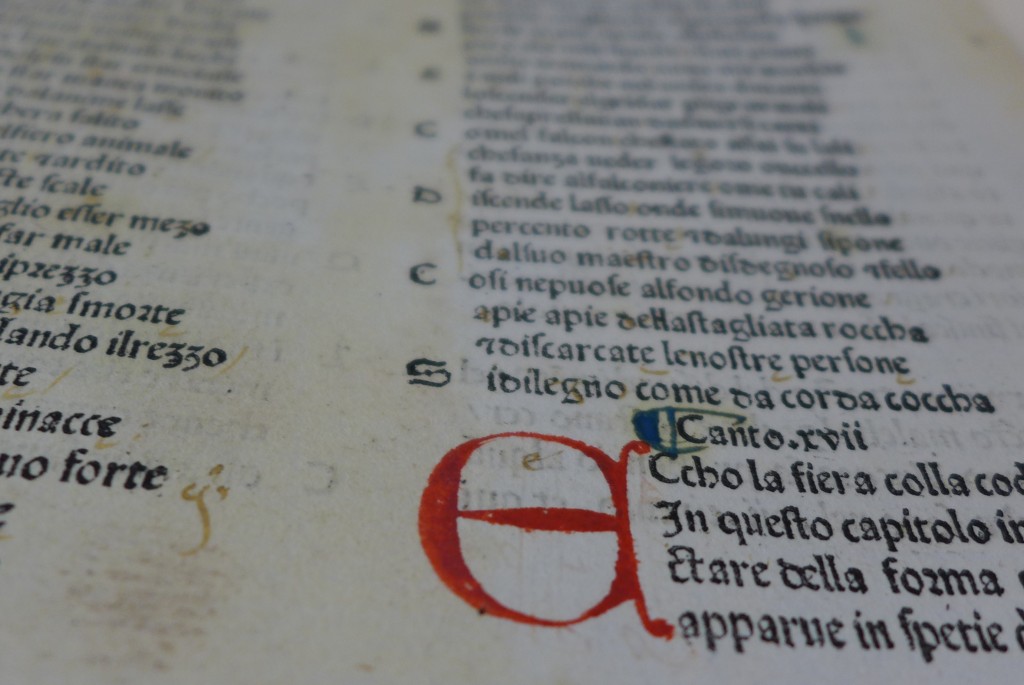

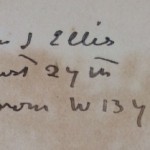

Our edition of ‘Astomomiae Pars Optica’ includes notes on the front endpapers handwritten by Francesco Tognetti, an Italian man of letters c.1810-1820. His notes discuss Kepler’s life and work and are signed ‘from Tognetti’ suggesting that the book was given by him as a gift.

I used to measure the heavens,

now I shall measure the shadows of the earth.

Although my soul was from heaven,

the shadow of my body lies here.

Kepler’s self-composed epitaph

Sources:

- Kepler, J (1604) Ad Vitellionem Paralipomena, Quibus Astronomiae Pars Optica Traditur. Frankfurt: Claudium Marnium and Haeredes Joannis Aubrii [Reserve 520]

- Di Liscia, Daniel A., “Johannes Kepler”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2015 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- Josh Skydel and Sam Whelan, Lutheran Reformation to a New START

- Science Photo Library

- Rabin, Sheila J. (2010) Oxford bibliographies: Johannes Kepler. Oxford: oxford University Press Accessed: 08/03/2016 [DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780195399301-0047]

- Johannes Kepler 2016. Britannica Academic. Retrieved 08 March, 2016