Written by Louise Cowan, Trainee Liaison Librarian

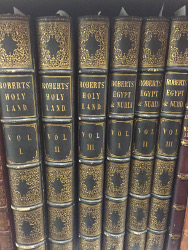

This Travel Thursday post features the masterful landscape illustrations of Scottish painter and traveller, David Roberts. Presented in six volumes, both ‘The Holy Land’ and ‘Egypt and Nubia’ [OVERSTONE–SHELF LARGE 34I/07] were published between 1842 and 1849 by F.G. Moon. These hefty tomes contain detailed drawings alongside historical descriptions of various sites of interest in the Middle East. The prints, created by Louis Haghe, a prolific and renowned lithographer, have “come to be regarded as the chef d’oeuvre of the tinted lithograph,” (Price).

In the early 19th Century, travel was both difficult and expensive so few people were able to venture beyond their own towns and while photography was beginning to develop, “printed books of landscape and travel drawings were for most people their only window to the outside world,” (Medina Arts).

However, even the artists creating such drawings tended to rely on inaccurate or incomplete descriptions from travellers when composing their landscapes of foreign locations. Roberts was one of the first professional artists to visit the Middle East and compose his landscapes ‘on the spot’. He believed that, “there would be a great market in England and Europe for images of such exotic subjects,” (Medina Arts) and with subscribers to his work including Charles Dickens, John Ruskin, Queen Victoria and Tsar Nicholas 1 of Russia– Roberts was proved correct. His works continue to have importance today, giving a glimpse into monuments unseen by many and preserving some views that have been lost to time forever.

Setting out in 1838, Roberts sailed from Alexandria and travelled for eleven months up the Nile River, through Egypt and the Holy Land, recording “his impressions of landscapes, temples, ruins, and people in three sketchbooks and more than 272 watercolors,” (Metropolitan Museum). He also kept a journal of his travels, sections of which are quoted in the historical descriptions written by Reverend George Croly in the published volumes:

The ‘Colossal Figures in Front of the Great temple of Aboo-Simbel’, which represent Rameses II, are described by Croly as being, “the most beautiful colossi yet found in any of the Egyptian ruins,” and he notes the vitriol Roberts showed in his journal toward the, “contemptable relic-hunters, who have been led by their vanity to smear their vulgar names on the very foreheads of the Egyptian deities.”

The height of these enormous statutes is recorded at over fifty-one feet yet despite their size, Roberts affords them minute and careful detail in his artwork. It is therefore no wonder that leading English art critic, John Ruskin is quoted as saying that Roberts’ drawings, “make “true portraiture of scenes of historical and religious interest. They are faithful and laborious beyond any outlines from nature I have ever seen,” (Metropolitan Museum).

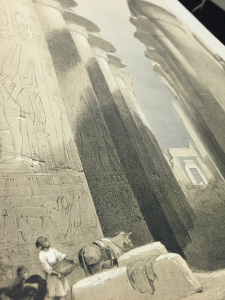

However, it is perhaps clear that Roberts was motivated to produce such beautiful drawings as he was inspired by the beauty of the landscapes and objects themselves. In the description accompanying his drawing of the ‘Central Avenue of the Great Hall of Columns in Karnak’ he is quoted as saying:

It is only […] on coming near that you are overwhelmed with astonishment: you must be under these stupendous masses – you must look […] to them, and walk around them – before you can feel that neither language nor painting can convey a just idea of the emotions they excite.

Indeed the introductory text to the collection celebrates the fact that, thanks to the efforts of previous explorers, “a visit to the Nile is not an adventure but an excursion.” The world of the Middle East had become more accessible and a journey there was more than worth the effort:

A voyage from Alexandria to Wady Halfa, will reward the traveller, by the emotions which the scenes and objects will excite, far beyond any power of promise.

Sources and Further Reading: