This month’s blog post was written by Chloe Wallaker, a final year BA English Literature and Film student at the University of Reading. Chloe has been researching our Crusoe Collection as part of her Spring Term academic placement based at Special Collections.

Today marks the 299th anniversary of the publication of one of our favourite novels – Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe. It is one of the most popular and widely published books today. The University of Reading Special Collections holds hundreds of editions and imitations of the novel as part of their Crusoe Collection, so I decided to visit and explore what the archives have to offer.

For a novel that was intended for adult readers, it was striking to discover the vast number of publications of Robinson Crusoe that were aimed at children. Different editions emphasise different aspects within the story and aim at children of different ages. I have chosen to showcase some of my favourite modern editions of the text that are aimed at children and published in the twentieth century.

The Rand-McNally edition of Life and adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1954)– CRUSOE COLLECTION–A1954.

I came across the edition published by Mcnally and Company (above), which includes the modernised text of Robinson Crusoe, with minor abridgements. The cover includes different illustrations referencing classical children’s literature, including Lewis Caroll’s Alice in Wonderland, that was also published in the eighteenth century and forms a part of popular culture today. The edition categorized Robinson Crusoe amongst famous children’s fairy tales and recognised it as an adventure story for young readers.

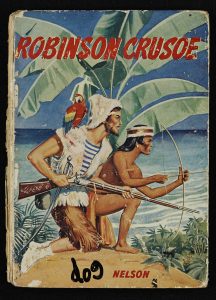

Nelson (1960), Robinson Crusoe – CRUSOE COLLECTION–A1960

There are many adaptations of the novel that are shortened for younger children. I discovered Nelson’s adaption of the text. The edition is published to be told to children by adults, demonstrating how the story is constructed for very young readers as well as older children. This edition stood out to me as the cover focuses on the more mature and violent themes of the novel, including slavery and death, than the covers intended for older children. This made me question the appropriateness of the story in challenging its young children

- Hunia, Fran (1978), Robinson Crusoe, CRUSOE COLLECTION–A1954

- Wilkes, Angela (1981), The adventures of Robinson Crusoe — CRUSOE COLLECTION–A1981.

The adaptation published by Hunia (above, left) encourages young children to read the story for themselves, instead of being read to. The cover suggests the story focuses on the relationship between Crusoe and Friday, as opposed to focusing on the adventure story which most of the publications adopt to appeal to children. This demonstrates how Robinson Crusoe not only appeals to children through entertainment, but teaches moral lessons, highlighting the pedagogical value of the novel.

Most of the children’s adaptations use illustrations to appeal to children. Wilkes’s edition (above, right) seems to construct the text to resemble a picture book. As well as focusing on the adventure aspects of the text, the publication focuses on the spiritual themes embedded within the novel, with its cover illustration resembling the biblical story of Noah’s Ark.

The publications I found most interesting were the imitations of the text, commonly described as ‘Robinsonades’, which reveal how Robinson Crusoe was not just a popular novel, but became an identifiable piece of popular culture. Crocket’s imitation of the text constructs Crusoe as a child figure, creating an identifiable protagonist for children. The edition takes the themes of adventure from the original text and constructs a version of the novel that is perhaps more suitable for children.

- Crockett, S.R (1905) CRUSOE COLLECTION–A1905.

- Ballantyne, R.M (1970), The dog Crusoe –CRUSOE COLLECTION–A1942-2013 [BOX].

Perhaps the most interesting imitation of the novel is Ballantyne’s edition. This edition focuses on the relationship between a dog and his master, resembling the relationship between Crusoe and his man Friday. The edition removes the mature and violent themes of slavery, which could be considered inappropriate aspects of the novel, and constructs a pet-master relationship, which would appeal to children and in terms they could understand.

Some of the editions that stayed more true to the novel seemed to present problematic themes for children. This made me question the appropriateness of a novel that was intended for adults, being read by children. I found it interesting how each edition focused on different aspects and themes of the novel, demonstrating the number of ways in which the novel can be read and used to educate and entertain children. This investigation into the children’s editions of Robinson Crusoe has reminded me why the novel has remained a favourite read for people of all ages and continues to be published today.

For more information on our Crusoe Collection, visit the Special Collections website, or email us at specialcollections@reading.ac.uk.

References:

Ballantyne, R.M (1970), The dog Crusoe, London: Abbey Classics, CRUSOE COLLECTION–A1942-2013 [BOX].

Crockett, S.R (1905), Sir Toady Crusoe, London: Wells Gardner, Darton & Co. Ltd, CRUSOE COLLECTION–A1905.

Defoe, Daniel (1954), Life and adventures of Robinson Crusoe, New York: Rand McNally & Company, CRUSOE COLLECTION–A1954.

Defoe, Daniel (196-), Robinson Crusoe, London : Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd., CRUSOE COLLECTION–A1960

Hunia, Fran (1978), Robinson Crusoe, London: Collins, CRUSOE COLLECTION–A1954.

Wilkes, Angela (1981), The adventures of Robinson Crusoe, London: Usborne Publishing, CRUSOE COLLECTION–A1981.