We have a newcomer to our staircase entrance hallway – the stunning Pandora, by JD Batten. Pandora is a part of the University art collection, and has joined us from its previous home at the main library.

We have a newcomer to our staircase entrance hallway – the stunning Pandora, by JD Batten. Pandora is a part of the University art collection, and has joined us from its previous home at the main library.

In fact, however, Pandora had a home in the Special Collections building for over 30 years (until 1949) when it was St Andrew’s Hall. Pandora’s history is an interesting one, and we share below the story of how it was (re)discovered as well as its place in the history of art (Adapted from READING reading 13, Autumn 1990).

After the departure of the former School of Education from the Old Red Building to Bulmershe Court during the Easter Vacation 1990, a number of interesting artefacts associated with the University’s (and University College’s) occupation of the building came to light. None however was more interesting than the large picture in a fine but damaged gilt frame found in the basement.

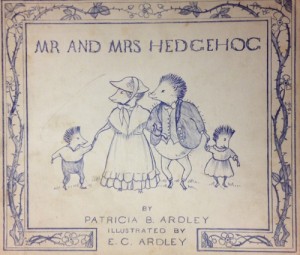

Close inspection with Dr Anna Robins of the Department of History of Art revealed the stunning colours of a beautiful pre-Raphaelite painting dated 1913 and signed JDB. Dr Robins was soon able to establish that the artist was John Dixon Batten (1860-1932), a late Pre-Raphaelite who had been recently brought to public attention in The Last Romantics exhibition of 1989 at the Barbican Gallery, London. Batten was well represented there by paintings in tempera, coloured woodcuts and two illustrated books, Celtic Fairy Tales and More Celtic Fairy Tales, ed. Joseph Jacobs, which were lent by the Library (note: these and other Batten works are now available in Special Collections as part of the Children’s Collection).

Although Pandora was exhibited at the Royal Academy as late as 1913, its style and subject make it Victorian. Like many Victorian artists including Lord Leighton, President of the Royal Academy between 1878 and 1896, Batten had a lively interest in classical myths which had great appeal to an age which strongly identified with the Ancient. Mr Alan Windsor (Department of History of Art) identified the passage from Hesiod which inspired Batten’s Pandora – ‘The fictile likeness of a bashful maid Rose from the temper’d earth, by Jove’s behest, Under the forming god: the zone and vest Were clasp’d and folded by Minerva’s hand.’

The Victorians were deeply resistant to depictions of the nude in modern day settings. Whistler made a few attempts to test the moral climate but with little success. Yet it is one of the paradoxes of a paradoxical age that paintings of the nude with a mythological reference were accepted and indeed even welcomed at the Royal Academy, that most respectable of art institutions. Thus Batten’s composition which portrays Pandora as a nude statue being brought to life in the presence of other gods and goddesses was by no means unconventional. Like all pictures Pandora needs to be understood within the prevailing codes of taste and censorship of its time rather than of our own.

One of the most interesting aspects of Pandora is its technique of tempera on fresco. Tempera painting is a method by which dry pigment is mixed with egg yolk. The oily properties of the yolk create a hard smooth surface when the medium dries. Batten was one of the leading participants of the tempera and fresco revival in England. He was a founder member of the Society of Painters in Tempera in 1901 and its Secretary for twenty years. The society’s members admired the technical skill and craftsmanship in the art of the fifteenth century which they thought was sadly lacking in modern painting. Batten was often praised for his skill as a tempera painter. Indeed, he was asked to speak about tempera painting on the occasion of the Ashmolean Museum’s tempera exhibition in 1922. (Batten’s lecture was subsequently published in the Studio magazine with numerous illustrations.) Yet the majority of his pictures remain untraced which makes the discovery of Pandora so exciting for the University and the art world at large.

John Batten had been for some years External Examiner in the Department of Fine Art and had apparently revived there the art of wood block colour printing in which he so excelled. According to Professor H A D Neville, Professor of Agricultural Botany since 1919, the picture had been in the University College’s possession from 1913 or 1914. In a letter of 1 February 1949 to Miss Ursula Martindale, then Warden of St Andrew’s Hall, he wrote: ‘I am almost certain that Miss Bolam [first Warden of St Andrew’s Hall] was asked to find room for it because no suitable place could be found for it in the University. The walls of Senior Common Room [Acacias] were already covered with portraits and the present Library [now Gyosei College Library] had not then been built. Childs [Principal of University College and first Vice-Chancellor of the University] told me that they had every intention of getting it a place in the University and would have done so but, when the 1914-18 war broke out, there was some chance of the University buildings being taken over by the Army and the tendency was to get things away from the University and not to bring more things in. At the end of that war, Miss Bolam had acquired some kind of right to the picture and no one dared to take it away. I remember when Senior Common Room was very much enlarged, I suggested that we claimed the picture but Childs was obviously afraid of facing Miss Bolam’s wrath if we attempted it!’

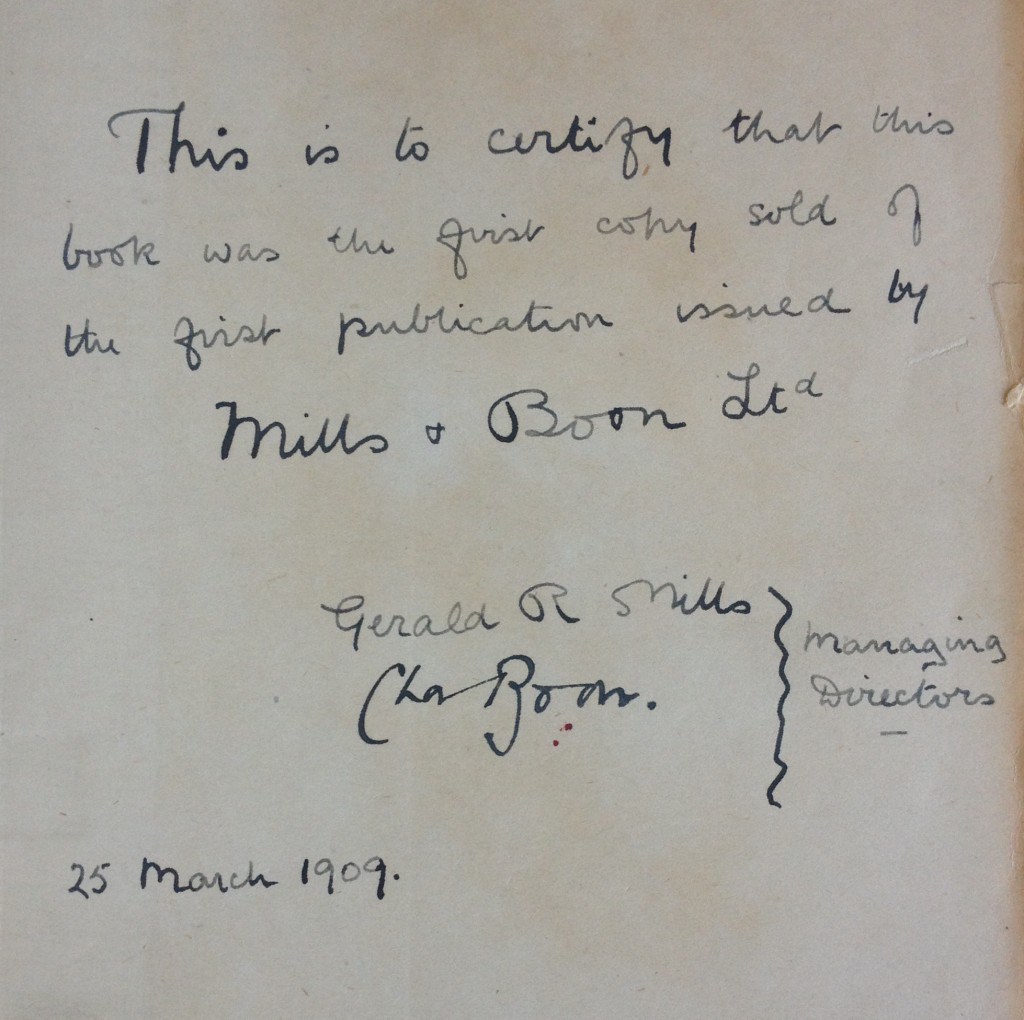

It is a good story and very much in keeping with the formidable reputation of Miss Bolam. It may also in essence be true except that the formal presentation of the painting to the University College did not take place until the autumn of 1918. A Council Minute of 25 October 1918 confirms this and adds that the picture was glazed and framed by the artist himself. The Council resolved ‘that Mr Batten’s picture Pandora be temporarily hung in St Andrew’s Hall on the understanding that it shall be transferred hereafter at the pleasure of the Council to a position in the main College buildings.’

The picture seems to have hung undisturbed in the Lounge at St Andrew’s for the next thirty years, except that in February 1922 it was sent to the Ashmolean, Oxford, for the tempera exhibition already referred to. According to a Minute of the Finance Committee of 10 March 1922, the picture occupied the place of honour in the exhibition and was highly praised in the Oxford Press in a review which ‘expressed satisfaction that the picture was the property of a public institution’.

Pandora returned to St Andrew’s Hall and seems to have remained in the Lounge there until 1949. The University took the opportunity to give Pandora the public display it clearly deserves when on 6 March 1992 the painting was unveiled in the University Library by the Chancellor, Lord Sherfield.

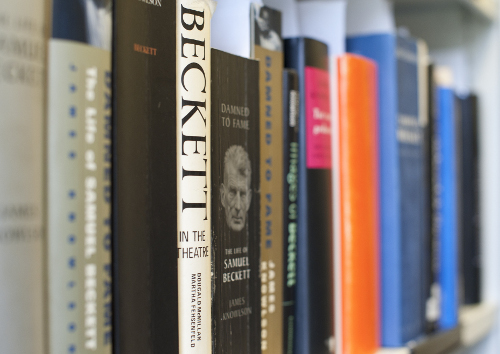

In 2013 the University of Reading acquired the hand-written manuscript for Murphy, Samuel Beckett’s first published novel and the first major expression of the central themes that would occupy much of his later work. This has been added to the Beckett Collection. The manuscript, described by Sotheby’s as the ‘most important manuscript of a complete novel by a modern British or Irish writer to appear at auction for many decades’, had been in private hands for the last half century. The manuscript fills six notebooks and provides a text that is substantially different from the final printed edition in 1938. Further details may be found in our earlier blog post.

In 2013 the University of Reading acquired the hand-written manuscript for Murphy, Samuel Beckett’s first published novel and the first major expression of the central themes that would occupy much of his later work. This has been added to the Beckett Collection. The manuscript, described by Sotheby’s as the ‘most important manuscript of a complete novel by a modern British or Irish writer to appear at auction for many decades’, had been in private hands for the last half century. The manuscript fills six notebooks and provides a text that is substantially different from the final printed edition in 1938. Further details may be found in our earlier blog post.