Written by Louise Cowan, Trainee Liaison Librarian

Written by Louise Cowan, Trainee Liaison Librarian

This week’s Travel Thursday takes us to Sweden with eminent scientist Thomas Thomson. As the first teacher of practical chemistry in a British university and an elected fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (Morrell, 2004) it is no surprise that much of Thomson’s travelogue has a scientific focus.

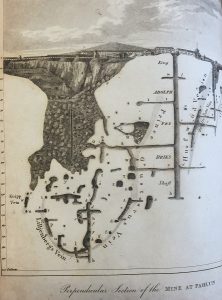

In particular, Thomson devotes a considerable amount of his work to mineralogical observations and detailed descriptions of the mines he visits on his journey. One such mine is the copper works at Fahlun, one of the oldest in Sweden, which Thomson describes as being 200 fathoms deep and constructed, “according to very scientific and sound principles.” The maps accompanying his description are wonderfully detailed and were “copied from a very accurate set of charts of this mine, constructed by Baron Hermelin.” Interestingly, the mine remained open until 1992 and is now a Unesco World Heritage site

(Falu Gruva, 2014) meaning travellers to Sweden today are still able to tour the mines as Thomson did over one hundred years ago!

Thomson’s scientific interests were also piqued during his time in the Swedish capitol, Stockholm. In particular, he remarked that the Academy of Sciences, “deserves to be visited by every scientific foreigner who goes to Stockholm.” It does indeed sound like a fascinating place with an interesting variety of objects. For example, among their collections could be found a piece of bread which in “some parts of Norway and the north of Sweden is made of the bark of trees.”

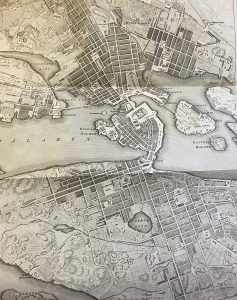

Elsewhere in Stockholm, Thomson also marvelled at the curious collections in the Arsenal, especially the “the clothes and hat worn by Charles XII when he was shot in the trenches before Frederickshall,” which remained bloodstained from the fatal wounds. He visited most of the churches the city had to offer but did “not consider it as worthwhile to give a particular description of them,” and finally found the perfect spot to view the city – a magnificent bridge joining the central island of Stockholm to the main continent:

When you stand upon this bridge and look south, the King’s palace immediately strikes the eye, a building of immense extent, and seen with peculiar advantage from the bridge. Toward the east, the inlet of the Baltic stretches itself before the eye covered with ships, and thick scatted with barges plying from place to place under the direction of women; for the boats in Stockholm are all rowed by women.

Again Thomson provides a beautifully detailed map to help illustrate his descriptions. This map of Stockholm was copied from one published by Fr. Akiel in 1795 and although it had been updated and was considered one of the most accurate maps of the town, Thomson believed, “the style is somewhat blameable, as not sufficiently distinguishing between what is town and what fields. His object seems to have been to swell the town as much as possible, and conceal its real dimensions from the eye.” Thomson therefore made several corrections in his own copy.

Overall, Thomson travelled more than 1200 miles in a short seven weeks and though his descriptions of the sights and collections he encounters across Sweden are full of lively detail and interest, it is of course the human stories that provide the colour and character to the narrative; from the wily Olof Essen, a spoke-maker who treated Thomson very ungenerously “with regard to the rate at which he let us have horses from Lilla Oby to Oby;” to the group of English sailors in Stockholm who “had all got quite drunk and had fallen together by the ears, to the number of ten or twelve in the middle of the street, and raised a clamour that was quite diabolical.” Thomson was so mortified by this particular scene that he went so far as to claim:

In most Englishmen who travel, as far as I have had an opportunity of observing them, there is an unaccountable wish to let foreigners, with whom they associate, know that they despise them.

On a lighter note, one of my favourite pieces of the human story in Thomson’s travelogue comes at the end, in an appendix chart showing the population and professions of Sweden:

Total number of chocolate makers? One – but he is a master of his art!

Sources:

Thomson, Thomas (1813) Travels in Sweden during the autumn of 1812. London: Robert Baldwin [Overstone 26F/23 – available upon request]

Jack Morrell, ‘Thomson, Thomas (1773–1852)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Oct 2006 [http://www.oxforddnb.com.idpproxy.reading.ac.uk/view/article/27325, accessed 6 July 2016]

Falu Gruva (2014) Welcome to Fahlun Mine http://www.falugruva.se/en/