Currently working at the University of Reading as Staff Engagement and Communications Officer, Jeremy Lelean previously worked as a dealer in antiquarian and collectable books. In today’s blog, Jeremy takes a closer look at the Overstone Library, the foundation collection of the University Library.

- Detailed illustration of Trajan’s Column, from Piranesi’s Colonna di Trajano e di Antonio Pio (OVERSTONE–SHELF LARGE 1H/01). The Overstone Library holds several other works by Piranesi, such as Vedute di Pesto and Vedute di Roma.

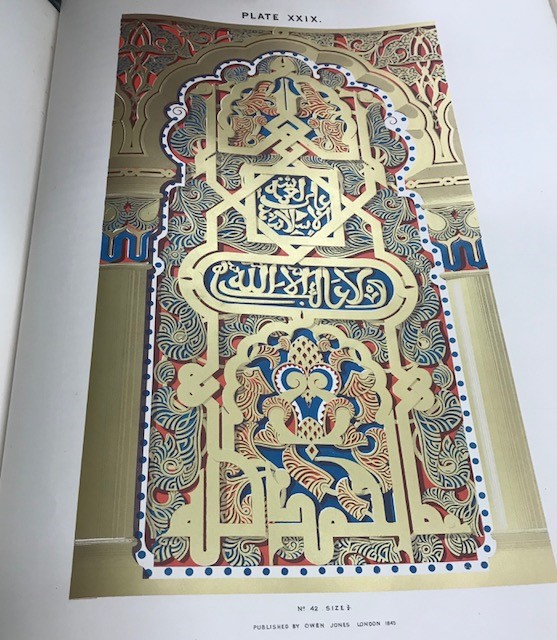

- Patio de los leones (Plate XXIX), taken from Plans, elevations, sections, and details of the Alhambra by Jules Goury, with illustrations by Owen Jones and Pascual de Gayangos y Arce (OVERSTONE–SHELF LARGE 33J/05-6)

- The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt, & Nubia by David Roberts (OVERSTONE–SHELF FOLIO 29J/13). The Overstone Library has several other editions of David Robert’s works.

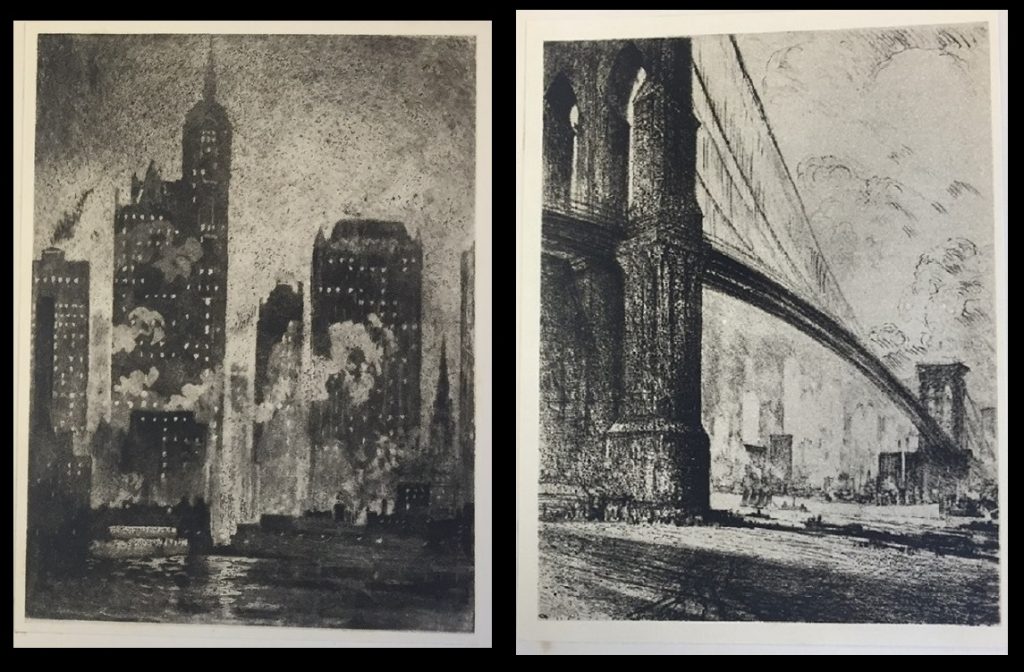

I work in science communication, most recently with research into soil, and when looking at the Overstone Library I was struck by a certain similarity. Both are somewhat ignored but just as there is treasure in soil there is treasure in the Overstone Library. This is clearly seen in this stunning (and surely longest ever) illustration of Trojan’s Column from Colonna di Trajano e di Antonio Pio (1770). Or more obviously valuable items like Jules Goury’s Alhambra (1842-1845) or David Roberts’ The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt, & Nubia. But, there is also a less obvious significance to the Overstone Library. I love books but when I say this, people often confuse this with liking literature. It is the books themselves that interest me: every library or collection is a treasure trove waiting to be discovered.

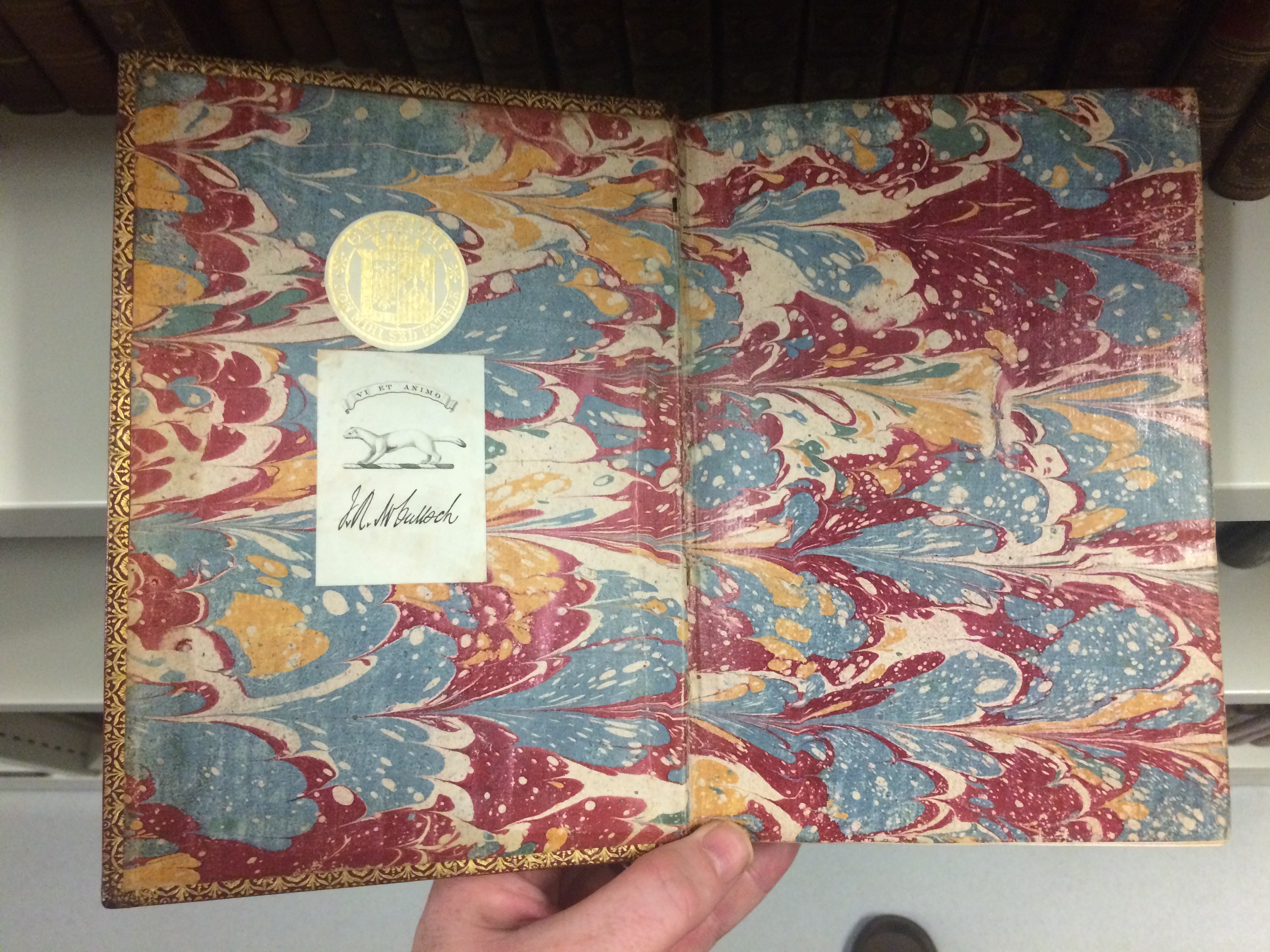

How the Overstone library was created can be clearly followed in the two bookplates seen in many of the volumes. Though fallen out of fashion now, bookplates were commonly used from the days of early printing into the mid twentieth century. We know, therefore that this library was collected by two people: that is John Ramsay McCulloch and, subsequent to his death, Samuel Jones Loyd, Baron Overstone. Using bookplates as a sign of ownership was important to the sort of collecting that led to the creation of these libraries in the nineteenth century. Having a library was a great sign of being solidly middle class, a notoriously important thing in Victorian England. Once one had made a fortune, showing one’s wealth was important but also one’s knowledge and culture. The books in the Overstone Library demonstrate this well but the significance is that it is still intact and all together.

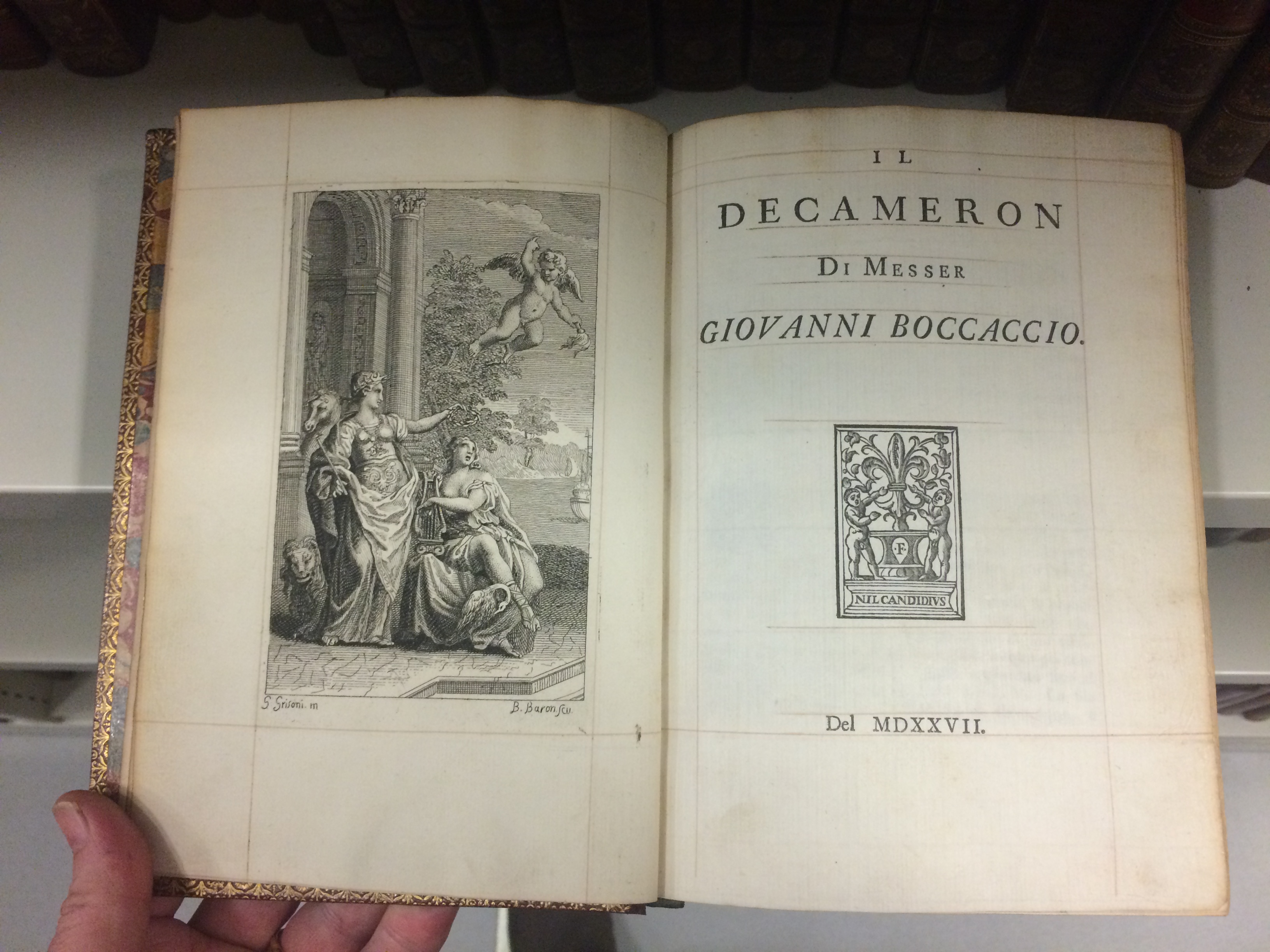

Many of the books the library contains are not that remarkable and certainly none are very rare. There are many eighteenth and nineteenth century editions of books and poetry we could recognise today, as well as standards of the time that might have been forgotten like The Fables of Aesop or the Decameron (The Ten Days) by Giovanni Boccaccio. In my previous work as a dealer in antiquarian and collectible books I would often see odd volumes from such collections but never saw an intact library like this. Most of these libraries had been broken up post-First or Second World War (this library came to the University in 1920). So, to see such a collection as a whole tells us a lot about the aspirations of Overstone and the wider Victorian middle class.

- Bibliotheca Maphæi Pinellii Veneti (1787), OVERSTONE–SHELF 5G/13.

- Dictionnaire des sciences philosophiques, Vol. 1-6 (1844-52), OVERSTONE–SHELF 5E/15.

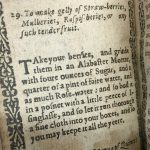

More social history can be unearthed by looking at the books as objects rather than for what they contain. Until paper tax was abolished in 1846, books were the preserve of the wealthy and were sold as paper text blocks, without covers, so the owner would have them bound, if not uniformly, then sympathetically. This can be seen in these two French reference books (see above) showing Overstone’s choice in binding and decoration. As well as this we can see the Victorians’ love of decoration, for example, in the Decameron (see below). The gilt decoration on the cover is perhaps enough but, if it wasn’t, open the book to see how it continues inside and the beautiful marbled endpapers. You may not agree with the Victorians’ idea of taste but have to admire their commitment to it in all things, even their books.

So the next time you hear the word library, think less of a building or even a collection of books, but of treasure waiting to be discovered!

- The front cover of Decameron (1725), showing the gilt decorations. (OVERSTONE–SHELF 19F/3)

- The frontispiece, including the gilt decorations around the edges.

- The marbled pages of the Decameron, including the bookplates of McCulloch and Overstone.

Click here for more information on the Overstone Library. If you have any further queries, or wish to view items from the Library, email specialcollections@reading.ac.uk.